| Caitlyn Speier |

The Heartbreak Kid plays at the Trylon Cinema from Friday, May 9th, through Sunday, May 11th. For tickets, showtimes, and other series information, visit trylon.org.

This past year, one of the most kind, smart, and justice-oriented people I’ve ever had the honor of calling a friend voluntarily left this world. Saying goodbye has been utterly… confusing. I suspect in large part because we honestly didn’t talk much anymore. Every moment of my grief has been punctuated with the question, am I even allowed to have these feelings? Despite the distance, I still feel the loss. Trying to understand these feelings, I spiraled into more questions than I could possibly address here. Old beliefs were called back into question, and to some extent, every relationship I’ve ever had was put under the microscope. Over and over, the questions became: What does it mean to love someone? What does it mean to love someone even if you know every single thing about them, and yourself, will change? What does it mean to love someone even if you know they will do things that hurt you, and you will do things that hurt them? These aren’t new questions, but they have been entirely muddled, I fear, by the concept of romance. So let’s start there: does romantic love even exist? And there is simply no better case study to investigate this question than director Elaine May’s 1972 film, The Heartbreak Kid.

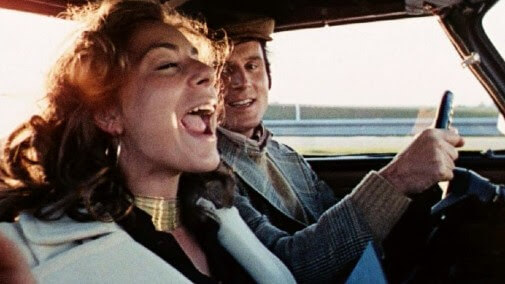

Now, anyone who’s seen The Heartbreak Kid can tell you this is not a compelling movie to pick to make the strongest possible case in favor of romance. The film begins with the perfectly slimy character of Lenny Cantrow, played by Charles Grodin, marrying soon-to-be 22-year-old Lila Kolodny, played by Jeannie Berlin. While on their honeymoon, Lenny meets and strikes up an emotional affair with a college student (Kelly Corcoran, played by Cybill Shepard) on vacation with her wealthy family. While STILL on their honeymoon, Lenny tells Lila he’s decided to end their marriage. He then moves to Minnesota to pursue Kelly, only to be forcefully and repeatedly rejected by her father, who had expressed a similar distaste over vacation. After a little begging from Kelly and groveling from Lenny, Mr. Corcoran eventually provides his blessing, and the film concludes with Lenny and Kelly getting married. There’s no denying it, this is not a romantic movie. It is, however, an honest one.

As a 25-year-old woman in the year 2025, I myself have only ever had one romantic partner. It was a teenage romance that left me asking questions about “what the hell all of that was” for a lot longer than I am proud to admit. As I look back on that romance now, through our collective permanent public record (Instagram feeds), I can see more clearly how I fit into the line of four or five back-to-back blond girlfriends. It’s difficult for me to talk about now without sounding like a strange and scorned high school ex, but all in all, it was an exceedingly sweet introduction to romantic love. It did, however, leave me with the unshakable feeling that something about my understanding of the situation was seriously off. I’m reminded of stories my family tells about how, as a small child, I would confuse my mother’s twin sister for her. What can you do but laugh when presented with the tragedy of a child running up to a woman who is not their mother but looks exactly like her asking “are you my mommy?” Elaine May similarly laughs in the face of such tragedy in The Heartbreak Kid. We’re currently living through a time of heightened gender disparities relating to romantic expectations. Through Lenny’s behavior, May simultaneously speaks to the lie that is romance in an American context and the risks that come with pursuing it.

C.S. Lewis provides a definition of romantic love in his book The Four Loves that effectively communicates much of what is going on in the abstract portions of the popular American understanding:

Eros makes a man really want, not a woman, but one particular woman. In some mysterious but quite indisputable fashion, the lover desires the Beloved herself, not the pleasure she can give. No lover in the world ever sought the embraces of the woman he loved as the result of a calculation, however unconscious, that they would be more pleasurable than those of any other woman. … in Eros, a Need, at its most intense, sees the object most intensely as a thing admirable in herself, important far beyond her relation to the lover’s need… If we had not all experienced this, if we were mere logicians, we might boggle at the conception of desiring a human being, as distinct from desiring any pleasure, comfort, or service that human being can give. And it is certainly hard to explain. Lovers themselves are trying to express part of it (not much) when they say they would like to “eat” one another. Milton has expressed more when he fancies angelic creatures with bodies made of light who can achieve total interpenetration instead of our mere embraces. Charles Williams has said something of it in the words, “Love you? I am you.” …Without Eros sexual desire, like every other desire, is a fact about ourselves. Within Eros it is rather about the Beloved. It becomes almost a mode of perception, entirely a mode of expression. It feels objective; something outside us, in the real world. That is why Eros, though the king of pleasures, always (at his height) has the air of regarding pleasure as a by-product. To think about it would plunge us back in ourselves, in our own nervous system. 1

I love this definition because it captures so many of the alluring parts of the promise of romance while also highlighting some of the potential codependent assumptions built into the concept and ending in a peculiar note about our own nervous systems. Protection from the potential impacts of interpersonal inclusion or exclusion are one of the key functions of our nervous systems. In Judith Lewis Herman’s influential work Trauma and Recovery, she cites war and rape as her gendered paradigms for thinking about trauma.2 This paradigm reveals so so so much about how patriarchy, in our settler society, functions as effectively a blanket of developmental trauma that serves to establish a functioning system of labor production and extraction. Boys take, girls give. This is the myth everyone in settler society is tacitly expected to accept. And in order to make the myth a reality, it is basically guaranteed that some part of one’s own personal identity will need to be killed or reshaped.

According to my best assessment of popular internet discourse on the subject, what we are seeing now is a generation of people searching for connection while having either accepted or violently rejected some version of this belief system. For those who have accepted it, one of the most common next stops in deconstructing scripts surrounding romance is attachment theory. One of The Heartbreak Kid’s strongest features is that it serves as a perfectly concise display of the interconnected workings of the three “insecure attachment styles.” Lila exists as our anxiously attached heroine, asking “Do you love me?” immediately after marriage. Lenny demonstrates fearful avoidance, telling Kelly’s father “I didn’t come out here to negotiate, I came here to fight for Kelly.” And Kelly reigns as the all-powerful dismissive avoidant as she is so underwhelmed by Lenny’s romantic overtures once back in Minnesota that he is confused that it seems like she doesn’t even remember him. The reason I want to talk about these characters’ relationships in terms of attachment rather than love at this point is because much of what we witness in this film is what it looks like when you’re attached to someone rather than in genuine connection.

“In quick, out quick. That’s what they taught us in the Army,” Lenny explains to justify discarding Lila. Lenny briefly mentions his service a few times throughout the movie, each time reminding the viewer of some of the larger political forces that influence these characters. Similarly, Kelly’s father exists as a successful American businessman, reminding the viewer of the economic forces that influence these characters. Mr. Corcoran takes one look at Lenny and makes an immediate assessment of him as a disingenuous person. In every interaction between Lenny and Mr. Corcoran we are watching two of the quintessential archetypes for American men, the soldier and businessman, interact. Lenny does the only thing he knows how to do—bullshit and fight. Mr. Corcoran does the same—offer cash and intimidate. Eventually though, Mr. Corcoran does give in because ultimately, at least to some degree, Lenny’s bullshit is consistent with American scripts surrounding romance. After Kelly and Lenny’s wedding, Lenny is left to repeatedly flounder in social interactions, not even able to hold the attention of children. “Ten… I was ten,” he tells us as his final line of the movie, leaving us to ask, how old is he now?

A growing body of research questions some of the assumptions built into and implications that come from attachment theory’s distinct orientation toward two-parent households. It seems undeniable that most (if not all) family systems are more complex than the nuclear family structure. Kim Tallbear offers us a potentially more complex understanding of romantic love through her work in relationship anarchy and critical polyamory. She reflects on relationships as avenues for self-actualization and growth, explaining “Different personalities and social ways of moving in the world help us partially re-socialize one another. With the aid of lovers past and present, including intellectual and other loves whose actual bodies play less to no part in our intimacies, we are ever becoming.”3

When Lenny ends things with Lila she is so genuinely distraught and confused by what he is saying that she thinks he’s telling her that he’s dying. When he clarifies that no, he’s just ending their marriage, she becomes significantly more distraught, potentially because what she was experiencing internally went from possible future death to immediate emotional death. To feel truly alone is to be dead; it is disconnection. Disconnection is when some part of our mind, body, or soul lifts itself off the ground and walks away from our shared reality. Much of what we see in this movie is not love. Rather, what we witness are desperate attempts to cling to another and succeed. So many of the popular conversations surrounding love today involve setting strict limitations and expectations that carry the same rigidity as the law, because frankly, a lot of the guidelines have been thrown out the window! Seemingly every part of what is happening and has been happening in American society presents the challenge for every person to develop their own unique belief system divorced from traditional American scripts. According to mine, to feel love is to be told by your mind, body, and soul that you’re in connection with kin. Choosing love consists of seeking out and working to preserve that connection to ourselves and others. And, in the words of bell hooks, “the moment we choose to love we begin to move towards freedom, to act in ways that liberate ourselves and others.”4 Everything else is just heartbreak!

Notes

- Lewis, C.S. “Eros” Chap. 5 in The Four Loves, (London: Geoffrey Bles, 1960), 109-111 https://ia600801.us.archive.org/3/items/fourloves01lewi/fourloves01lewi.pdf

- Herman, Judith Lewish. Trauma and Recovery, (Basic Books, 1992).

- Kim Tallbear, “Looking for Love in Too Many Languages…Polyamory? Relationship Anarchy? Dyke Ethics? Significant Otherness? All My Relations?,” The Critical Polyamorist Blog, March 25, 2016, http://www.criticalpolyamorist.com/homeblog/looking-for-love-in-too-many-languagespolyamory-relationship-anarchy-dyke-ethics-significant-otherness-all-my-relations

- hooks, bell. “Love as the Practice of Freedom” Chap. 20 in Outlaw Culture, (New York: Routledge, 2006) 289.

Edited by Olga Tchepikova-Treon