| J.R. Jones |

The Friends of Eddie Coyle plays at the Trylon Cinema from Sunday, May 18th, through Tuesday, May 20th. For tickets, showtimes, and other series information, visit trylon.org.

George V. Higgins was a crime writer’s crime writer, which may be another way of saying he never enjoyed the same level of success as some of his fans. Elmore Leonard—whose fiction inspired Get Shorty (1995), Jackie Brown (1997), and Out of Sight (1998)—remembered Higgins as the novelist who taught him how to write about the criminal underworld. Dennis Lehane—whose novels provided the source material for Mystic River (2003), Gone Baby Gone (2007), and Shutter Island (2010)—described Higgins’s 1969 debut novel, The Friends of Eddie Coyle, as “the game-changing crime novel of the last fifty years. … It casts such a long shadow that all of us who toil in the genre known as American noir do so in its shade.”1

Despite such lavish praise, only two of Higgins’s novels have been adapted to the big screen: The Friends of Eddie Coyle (1973), directed by Peter Yates, stars Robert Mitchum as the title character, a low-level Boston gun runner caught between his clients and an aggressive police detective who might be able to keep him out of prison. Many years later, writer-director Andrew Dominik (The Assassination of Jesse James by the Coward Robert Ford) turned Higgins’s third novel, Cogan’s Trade, into Killing Them Softly (2012) with Brad Pitt as the hit man sent to clean up after a couple of two-bit hoods pull off an armed robbery of a mob-protected card game. Each takes a different approach to Higgins’s fiction, but they share in common his unimpeachable ear for street talk and his understanding of the criminal codes that link these men together.

Born in 1939, Higgins started out as a journalist, but after covering mafia trials in Providence, Rhode Island, he decided to earn a law degree. By the late 1960s, he was serving as assistant U.S. attorney for Massachusetts, investigating organized crime. This experience clearly informed his fiction, which is coldly factual and grimly realistic, worlds away from the romantic nightscapes of Raymond Chandler or Dashiell Hammett. You can tell that Higgins spent a lot of time reading transcriptions of surveillance tapes: his dialogue is expressively ungrammatical, illuminating the constricted lives of his lower-class Boston characters. His day job so taught him the value of physical evidence that he spends the first 90 pages of Eddie Coyle referring to his title character as “the stocky man.”

Critics recognize Higgins as an innovator for the way he destabilized the moral universe of the crime story. “Gone was the policeman or private-eye protagonist, who periodically reassured the reader that order was achievable in a troubled world,” observed John Hamilton in the Guardian. But the true brilliance of Higgins’s crime writing lies in its perfect marriage of form and meaning. Nearly every chapter of The Friends of Eddie Coyle or Cogan’s Trade unfolds as a conversation between two men; by the end of the book you grasp that the business of crime requires people to keep their relationships private, and that the business of convicting them in court consists largely of detecting, exploiting, and ultimately exposing those relationships.

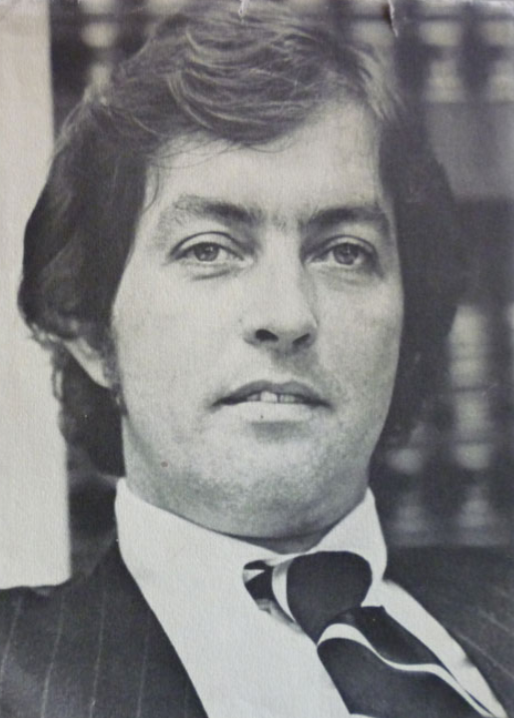

George V. Higgins, 1975. Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

In casting an already-iconic Robert Mitchum as Eddie Coyle, Yates connected his movie with the grand tradition of film noir, which doesn’t necessarily harmonize with Higgins’s hyperrealistic approach. But Mitchum had grown up poor, and his rumpled, no-bullshit performance fits in perfectly with Yates’s gritty, Boston-area locations and drab New Hollywood vibe. As Eddie haggles with younger, hipper Jackie Brown (Steven Keats) over a gun purchase, refusing to buy from the same batch as another client, he explains how he got the nickname Eddie Fingers, Mitchum investing decades of authority in Higgins’s words:

Count your fucking knuckles. … I got four more. One on each finger. Know how I got those? I bought some stuff from a man that I had his name, and it got traced, and the man I bought it for, he went to M C I Walpole for fifteen to twenty-five. Still in there, but he had some friends. I got an extra set of knuckles. Shut my hand in a drawer. Then one of them stomped the drawer shut. Hurt like a fucking bastard.2

Screenwriter Paul Monash wisely sticks to Higgins’s plainspoken dialogue, finding the dramatic arc in each chapter’s one-on-one encounter. These successive conversational scenes, though well-acted by the players, present a cinematic challenge to Yates, who makes the most of the seedy environs and punctuates the talk with action set pieces, largely wordless, in which a four-man crew (who procure their weapons from Eddie) stage a series of daring bank robberies around suburban Boston. Eddie is getting squeezed for information about this by Dave Foley (Richard Jordan), a police detective who knows that Eddie has been convicted for a truck robbery in New Jersey, faces a sentencing hearing soon, and will do anything to avoid prison. Behind the cop’s manipulation lies the scheming Dillon (Peter Boyle), a shadowy bartender who feeds tips to Foley but publicly directs people’s suspicion toward Eddie. With friends like these, who needs enemies?

Higgins liked to drop his readers into the middle of a scene and let them puzzle out what was happening; the characters gradually identify themselves as they talk, but all we really learn about them is how they’re related and who they know in common. This narrative strategy can be disorienting on the page, and on screen it demands a high degree of concentration: if you can’t connect the characters, you can’t follow the plot. Mitchum is the ostensible star of The Friends of Eddie Coyle, but as Yates shuffles from one little conference to the next, and Eddie is slowly locked into place by his relationships with others, he seems less like the movie’s hero than its goat.

Cogan’s Trade was published in 1974, but Dominik updates the action to the feverish fall of 2008, when John McCain and Barack Obama campaigned against each other for the presidency even as the U.S. banking system melted down. Killing Them Softly riffs endlessly on the financial crisis and the federal bank bailout that addressed it, with President Bush and Treasury Secretary Hank Paulson turning up on radios and TV sets while the criminals do business. The slow-motion opening credit sequence shows ratty small-timer Frankie (Scott McNairy) emerging from a tunnel into a garbage-strewn lot as Obama orates on the soundtrack about “that promise that’s always set this country apart. It’s a promise that says each of us has the freedom to make of our own lives what we will.”

Yeah, right. Frankie is just out of prison and can’t find a job; he and his scuzzy Australian pal, Russell (Ben Mendelsohn), accept an assignment from small-time criminal Johnny Amato (Vincent Curatola) to stick up a mob-protected card game and split the take with him. Normally such a stunt would invite immediate execution, but there’s a wrinkle: Markie Trattman (Ray Liotta), who runs the card game, once hired guys to storm in and knock off his own game but was stupid enough to brag about it later. Now that word has gotten around, the finger of suspicion for any subsequent robbery will immediately fall on Trattman.

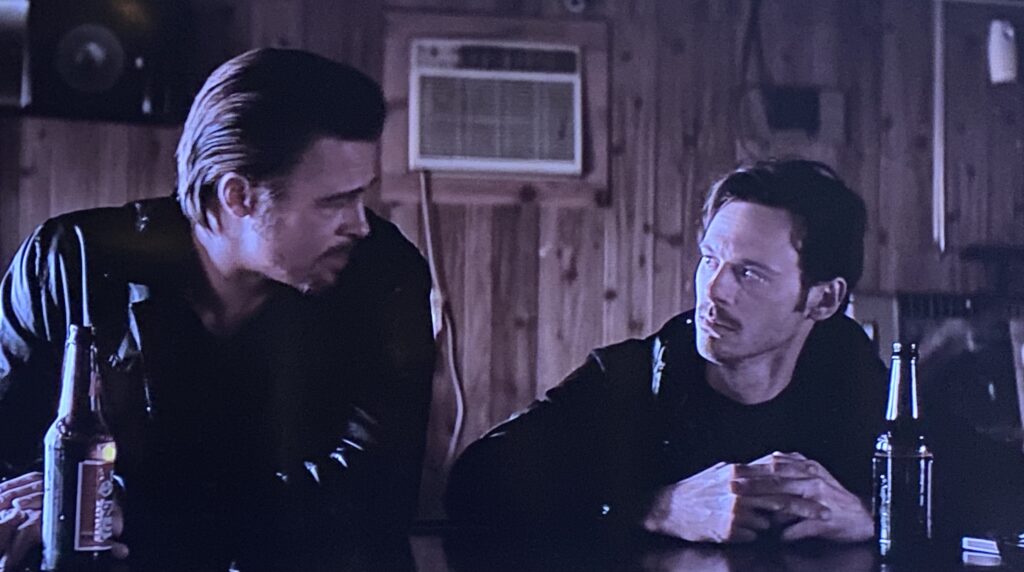

Like Yates’s adaptation of Eddie Coyle, Killing Them Softly strings together two-person dialogue scenes, though Dominik is blessed with more actors of Mitchum’s caliber—not just Pitt at his coolest, strutting around in cowboy boots and black leather as Jackie Cogan, but also Richard Jenkins as the anonymous driver giving him his orders and James Gandolfini as Mickey, a killer for hire who’s too busy drinking himself stupid over his crumbling marriage to complete his assignment. When Dominik cast Pitt as Jesse James, he discovered a streak of quiet menace beneath all that boyish charm, and he taps into it again here. Pitt steals his every scene, ranging from comic dismay as he watches Gandolfini self-destruct to icy disgust when Obama, declaring victory in Chicago, declares all Americans to be one. “Don’t make me laugh,” Cogan tells the driver. “In America, you’re on your own. America’s not a country. It’s just a business.”

Most chilling of all is the scene in which Cogan tracks down Frankie at a local tavern, introduces himself, and tries to persuade Frankie to set up his boss, Johnny Amato, for assassination. “Your friends are worried about you,” Cogan keeps telling Frankie without explaining who these friends are. Terrified, Frankie protests his innocence, but Cogan doesn’t care. “See, it’s not what you’ve been doing,” he purrs. “It’s what guys think you’ve been doing.” Trattman has already been executed, not because he staged the second stickup but because he made it look possible by blabbing about the first one. In the earlier movie, Eddie Coyle faces a similar problem: he may not have ratted out his associates to the police, but someone needs to be punished to teach everyone else a lesson.

Higgins never lived to see Killing Them Softly; he died of a heart attack in 1999, having published more than 30 books. None of them topped The Friends of Eddie Coyle commercially, and he often complained of being pigeonholed as a crime writer despite more adventurous novels in the 1970s and 80s. “My first published book was categorized as a ‘hard-boiled detective story’—it was not,” he wrote, “and most of the others since have been critically rated by reference to the same ill-chosen scale.”3 This, he argued, had deprived him of the general readership he craved, frustrated crime fans who read his later work, and generally inhibited his career. As Jackie Cogan points out, it’s not what you’ve been doing—it’s what guys think you’ve been doing.

Footnotes

1 Dennis Lehane, introduction to George V. Higgins, The Friends of Eddie Coyle (New York: Picador, 2010), vii.

2 Higgins, The Friends of Eddie Coyle, 4.

3 George V. Higgins, On Writing: Advice for Those Who Write to Publish (or Would Like To) (New York: Henry Holt and Company, 1990), 12.

Edited by Olga Tchepikova-Treon