| John Costello |

Outland plays on glorious 35mm at the Trylon Cinema from Sunday, June 1st through Tuesday, June 3rd. For tickets, showtimes, and other series information, visit trylon.org.

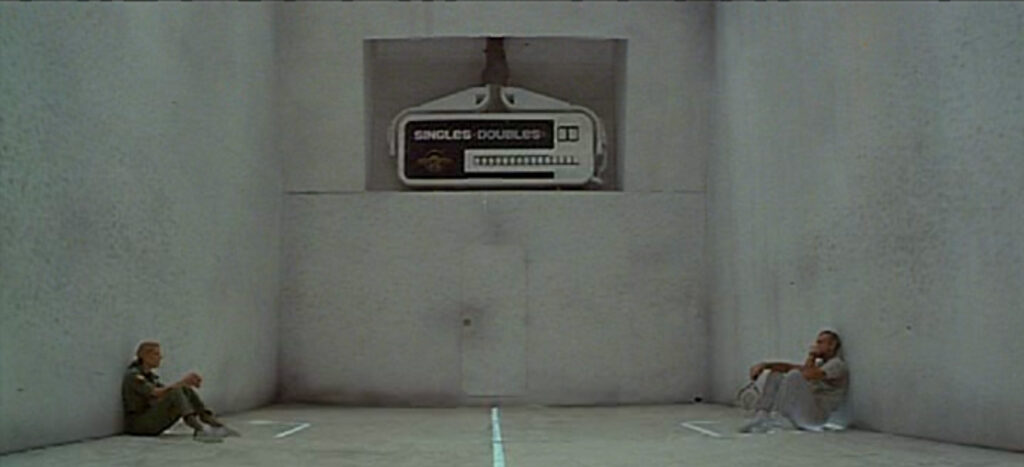

I’m supposed to write about the problem with science fiction tropes—mainly space Westerns—but I keep thinking about Peter Boyle’s portrayal of Sheppard in Outland (1981). Sheppard spends much of his time playing golf in his office, looking like he can’t afford a haircut, a beard trim, or clothing other than a golf polo and slacks. He manages a mining station franchise on Io, a moon of Jupiter where miners keep dying in bizarre accidents, like the one in the opening scene where a worker hallucinates spiders inside his spacesuit.

During the first staff meeting to welcome Sean Connery’s O’Niel, a newly arrived federal district marshal, Sheppard boasts about the mine’s productivity and bonuses while excusing how the miners “work hard and play hard.” Sheppard is more concerned about production quotas than prosecuting miners for crimes, let alone investigating their frequent deaths. When O’Niel doesn’t indicate that he’ll do whatever the mine boss wants, Sheppard tells O’Niel to come to his office for a talk, establishing the movie’s core conflict. Beyond his slovenly magnanimity, Sheppard menaces and demands compliance.

I couldn’t find any evidence that Boyle or writer-director Peter Hyams had Donald Trump in mind when they crafted Sheppard . Despite the temptation to draw parallels between the character and the politician regarding golf, corruption, subversion of law, disregard for human life, and rewarding loyalty over competence, I concede that Sheppard’s character was created years before Trump gained national attention, although Trump was already a known personality in Hyams’s native New York. (A 1980 Trump interview by gossip columnist and national figure Rona Barrett never aired, and Trump eventually received national attention via a 1985 60 Minutes interview.) Like Trump, Sheppard strives for success above all else and demands loyalty from those around him, including people not under his direct control.

Sheppard works for a criminal cartel controlled beyond the lunar mine, employs paid killers, trades his employees’ lives for productivity gains, bribes people to ignore his own crimes, and plans to retire early. There is no certain evidence that Trump works for a foreign power, although he did support a violent insurrection against the government, has encouraged actions risking the well-being of millions, and sometimes says he’ll leave office after his second term ends. Both Sheppard and Trump look like slobs when wearing golf attire.

The problem with this bad-faith comparison between Sheppard and Trump—besides that Sheppard seems to know how to do his job—relates to the problem with critically examining art works through a lens of tropes, such as those mentioned in the Turkey City Lexicon, hereafter TCL. Terminology alone doesn’t provide the critical skills people need to engage with art, especially absent an experienced guide, and a static lexicon fails to account for artistic progress. Although the first version of the TCL was published in 1988, I didn’t hear about it until a graduate of the Clarion West science fiction workshop recommended it recently.

The TCL contains useful advice about prose mistakes to avoid, yet even the prose advice betrays linguistic chauvinisms being challenged 40 years ago. The authors’ claims that the lexicon “does not require any shepherding by experts” and “is a guide (of sorts)” for “subliterate guttersnipes” belie the value of mentorship and the improvement of sci-fi writers’ literary skills in recent decades.

Where the TCL and trope analysis really fall apart is in the TCL’s thinly explained moral judgments of story types and backgrounds. A space Western is both a “Just-Like Fallacy” story background, thinly adapting pulp settings into space, and its own type of story background, one the TCL calls the “most pernicious suite of ‘Used Furniture,'” where “Used Furniture” is “a background out of Central Casting.”

I’ll note that the TCL criticizes using emotionally charged words (“subliterate,” “pernicious”) but not jargon.

Focusing on tropes reduces art to mechanical concepts detached from the artwork. Instead of encouraging curiosity and critical discussion of the work’s negative and positive aspects—Outland‘s casting of black actors in one-dimensional roles reflects persistent biases, while the lead female actor somewhat surpasses biases of that era—speaking in tropes demonstrates nothing more than mastery of tropes. Both writers and non-writers resort to this uncritical mode of thinking, applying “space Western” to a story containing Western elements set in space without considering the benefits of such displacement. Relying on tropes to engage with art is a bad-faith effort.

Hyams’s Outland is one of the few if only hard science fiction space Westerns—space suits, slow stellar travel, and greenhouses for growing food, although the full gravity is never explained. These details establish the genre shift the way stagecoaches, cowboys, and saloons establish a story in the Western genre. By focusing on the science fiction or space Western aspects of Outland, rather than the film’s social criticism, contemporary critics and viewers too easily dismiss the film, embracing the willful incuriousness of Trump (who notably thinks of people in terms of “central casting”) while missing Frances Sternhagen’s delightful one-liners.

Sternhagen plays Lazarus, a washed-up company doctor. “Most are one shuttle flight ahead of a malpractice suit,” Lazarus tells O’Niel about her profession. O’Niel struggles with his wife’s desire to live “someplace where you don’t broil or explode, air that smells like life, not like a ventilating unit.” He seems helpless to confront his son’s longing to visit Earth and admits he has “a big mouth” that leads to constant humiliation. O’Niel’s belief in justice and the intrinsic value of humans makes him a liability to the mine operators.

What makes Outland interesting is the film’s sharp focus on extraction capitalism’s disregard for human life. By shedding the Western setting for space, Outland avoids contending with America’s racist frontier history, instead focusing on capitalism’s drive to expand the frontier, from before George Washington’s funding of settlers in the Ohio River Valley forward to modern plans to turn a Middle East war zone into luxury resorts, both efforts removing the current inhabitants. (Regarding George Washington, see Greg Grandin’s The End of the Myth.)1

Outland was influenced more by an earlier political Western, High Noon (1952) than a shoot-em-up such as Frontier Marshal (1939). The latter movie is one of the earliest versions of Wyat Earp’s story. All three films incorporate domestic conflict, a marshal confronting criminal elements, a helpful doctor, and a violent final struggle. Unlike High Noon and Frontier Marshal, the gang leader in Outland, Sheppard , also runs the settlement.

Sheppard works for a company called ConsolidatedAmalgamated, less a name than two impersonal adjectives glued together. He succeeds by bribing, intimidating, and distributing illegal drugs to increase worker productivity. “There’s a guy like me on every mining operation all over this system,” Sheppard tells O’Niel while trying to bribe him. “Nothing here is wonderful. It works. That’s enough.”

Sheppard never considers the human cost of efficiency. The dead miners are jettisoned into space. New miners arrive to take their place.

Sheppard’s statement echoes the choice made by the townspeople in High Noon, who ignore the cost of surrendering to violent threats. Each time O’Niel finds a clue about the miners’ deaths and Sheppard’s involvement, he is sabotaged by corruption. Near the end of the film, O’Niel appeals to the mining community, knowing like everyone else that assassins are coming for him on Sheppard’s orders.

In the Western tradition, the calvary often rides to the rescue, usually against the indigenous people whose land was being colonized. Often, this is a deus ex machina plot device, a term included as a problematic story type in the TCL and originally coined by the ancient Greeks. In recent years, this plot device has taken the form of community rallying at the last moment in too many films to list, as if Hollywood wants sci-fi viewers to believe that reinforcements will always arrive in time. Outland and High Noon demonstrate how communities rally to avoid conflict, sacrificing the few people with enough conscience to resist.

I don’t mean to advocate for despair. Sometimes, as in Frontier Marshal, reinforcements arrive, people show up, and corrupt bullies are cast down.

In High Noon, the marshal tries to rally the townspeople to fight the returned criminal gang of murderers and rapists. The Justice of the Peace, about to flee before the criminals arrive, delivers a lesson about the return of tyrants. He relates an episode from ancient Athens, touted as the birthplace of democracy. The Athenians ousted a tyrant and later welcomed him with open arms, only to suffer executions and reprisals at the hands of the returned dictator. The implied lesson is that resisting a tyrant is better than yielding, with flight a last resort. Even though Trump’s return is increasingly marked by as much graft and incompetence as tyranny, the anecdote is an apt warning for America about the return of a leader who would act as an autocrat. The whipsaw emphasis on speed in pursuit of efficiency while causing suffering and ignoring legal orders are additional ways Trump reminds me of Sheppard. Sheppard aims to prevent his initial ouster by arguing that he is commonplace among mine managers. It’s an attempt to convince O’Niel not to resist.

High Noon heaps scorn on people who, like the ancient Athenians, acquiesced to a tyrant. Outland speaks to the value of building human connections and resisting tyranny.

When Lazarus asks O’Niel why he is fighting, Connery delivers some of the best lines of the movie: “There’s a whole machine that works because everybody does what they’re supposed to. I found out I was supposed to be something I didn’t like. That’s what’s in the program. That’s my rotten little part in the rotten machine. I don’t like it, so I’m going to find out if they’re right.”

Lazarus joins O’Niel, the pair risking their safety to resist tyranny. They persist against the machine.

Footnotes

1 Greg Grandin, The End of the Myth: From the Frontier to the Border Wall in the Mind of America (Henry Holt and Company, 2019).

Edited by Olga Tchepikova-Treon