| Dan McCabe |

The Panic in Needle Park plays at the Trylon Cinema on Wednesday, June 11th, as part of Bleak Week. For tickets, showtimes, and other series information, visit trylon.org.

“I thought it was something I could play. A few people could have done it, but it was a relatively castable role for me. I had made my theater bones playing these types of street characters, so I was grateful to have that choice for a first film.”1

Al Pacino on The Panic in Needle Park, from his 2024 memoir “Sonny Boy.”

What scene comes to mind when you think of Al Pacino? Michael Corleone calmly presiding over his nephew’s baptism while his associates slaughter his enemies in The Godfather (1972)? Detective Vincent Hanna exchanging round after round of gunfire with the professional thieves he’s been hunting for weeks in Heat (1995)? Coach Tony D’Amato giving the locker room speech of his life to his fractured football team in Any Given Sunday (1997)? For me, it’s the shootout in Heat, a movie that I played in the background, on a double tape VHS set, during many late-night paper writing sessions in college.

As one of the most acclaimed actors of his generation, or any generation, I could choose from hundreds of other options for the Pacino scene I love the most, each as iconic as the next. But what of his very first starring role, The Panic in Needle Park (1971)? Unless you’re a Pacino superfan, it’s probably not the first film that comes to mind in the pantheon of the actor’s finest moments. I watched it for the first time myself while preparing for this article.

What struck me most about Pacino’s performance in The Panic in Needle Park? I could see raw versions of the skill set that would make him a star—visions of the future roles he would go on to make famous.

What follows is a scene-by-scene comparison between Pacino’s performance in The Panic in Needle Park and his performances in Scarface as well as the miniseries Angels in America (2004). This will require discussion of plot points from these pieces. If you haven’t seen these works, and you plan to do so without any prior knowledge, here’s your off-ramp.

![A man standing and a woman lying on the floor in a cluttered apartment.]](https://www.perisphere.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/05/Panic_in_Needle_Park_003-1024x550.jpg)

Bobby and Tony Montana: Creating Redeeming Qualities in Unsympathetic Characters

By 1971, Pacino had already established himself as a promising actor in the New York theater scene, having won a Tony Award in 1968 for playing a young drug addict in the play Does a Tiger Wear a Necktie?. He plays a similar role in The Panic in Needle Park, as Bobby, a desperate small-time drug dealer and heroin addict navigating his way through a “panic”—slang for a period of exceptionally low heroin supply.

Roles depicting street characters came naturally to Pacino early in his career. Sadly, he drew from his experience growing up at the edge of poverty in the Bronx. As he details in his 2024 memoir, Sonny Boy,2 Pacino had close friends like Bobby—struggling and desperate young men who couldn’t see a future for themselves. An actor can only draw from lived experience so much, however, and Pacino’s early skill set endows Bobby with sympathetic qualities that keep the audience connected to Bobby throughout a film even when the character abuses his girlfriend and lets a puppy drown.

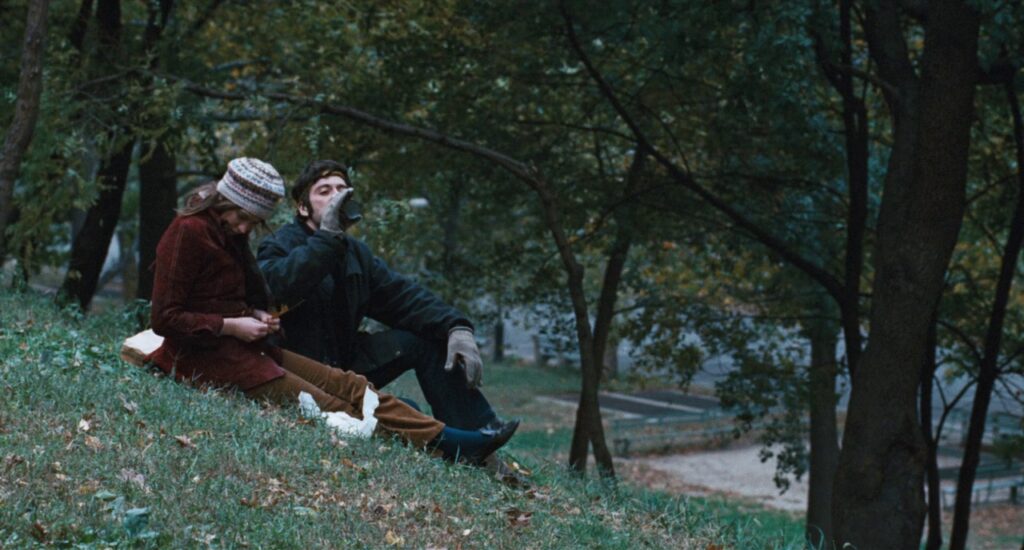

Look closely at the scene above, from early in the film. It is when we first meet Bobby. Pacino had won awards on stage playing guys like Bobby, so he certainly had the skill to play “apathetic, hard drug dealer.” We can see that quality by the way he swaggers down the street in the introductory shot to his character, and the confident way he carries himself in Marco’s (Raul Julia) apartment, ready to make a deal. Yet, his first line in the movie is when he tells Marco, “Your chick is sick.” After completing his sale (those drugs are definitely not “from Tangiers” as Bobby says), Bobby proceeds to go out of his way to give Helen (Kitty Winn) another blanket. Pacino is subtle, his character doesn’t berate Marco and he doesn’t oversell his concern for Helen—either of which could have resulted in melodrama that could pull the audience out of their suspension of disbelief. Pacino does just enough to connect Bobby to the audience—threading the needle perfectly between “hardman” and “soap opera love interest.”

We slowly learn throughout The Panic at Needle Park that Bobby is a fundamentally broken and toxic character, but he’s not a high-level monster. Don’t get me wrong, he’s horrible to Helen and to that puppy. However, Pacino’s work making him sympathetic to the audience is arguably less difficult than some of the even more malevolent characters he depicts later in his career. Tony Montana in Scarface, for example, kills dozens of people throughout the film and rules a cocaine empire with an iron fist. He would shoot a guy like Bobby for looking at him the wrong way without thinking twice about it. Yet, Pacino’s skill as an actor still connects Tony to the audience by portraying his redeeming qualities.

Tony’s positive aspects are woven throughout the film. Unlike Bobby, we don’t see him give a sick, young woman an extra blanket when he’s introduced. Rather, in his first scene, immigration agents ask Tony a series of questions. The agents are looking for an excuse to send him back to Cuba.

Tony doesn’t scream at them or confront them with hostility. He smiles and tells a story of his struggles living in a Communist regime. He doesn’t lie when the agents tell Tony they know he’s been to jail. He’s young, ambitious, and a straight-shooter who hates Communists. In other words, 1980s man.

Later in the film, we see Tony turn on the charm in other situations, mostly poolside. The aesthetic of Miami in the 1980s creates the potential to convey a certain level of cool, but Pacino’s demeanor and the way he delivers classic lines like, “In this country, you gotta make the money first. Then when you get the money, you get the power…,” sells Tony as someone who is both extremely dangerous yet somehow irresistible.

Bobby’s not half as dangerous or charismatic as Tony, but we can’t keep our eyes off of him, either. This is the nebulous, somewhat undefinable aspect of a leading actor that we call “screen presence,” but that quality does not occur in a vacuum. A key to Pacino’s success as a lead actor is cultivating this screen presence by portraying positive aspects of inherently negative characters like Bobby and Tony Montana.

Bobby and Roy Cohn: Power Dynamics and Underlying Characterization

About halfway through The Panic at Needle Park, Helen becomes a streetwalker in an effort to raise money to fuel her and Bobby’s growing drug addiction. After Bobby is released from a short jail stint, Bobby learns of her new profession. He beats her, but then they sleep together. After the sex, Helen reveals one of the men she’s “balled” is Bobby’s brother Hank (Richard Bright). This time, instead of reacting violently, Bobby whimpers. “Why’d you tell me that?” he repeats several times.

Pacino portrays a man trapped by his choices with little power to change them. He and Helen share a co-dependency almost as controlling as their drug addiction. Bobby is trapped and can’t find his way out. His addictions have robbed him of agency, so he lashes out with violence and whining. Pacino’s performance has an underlying consistency.

The way Pacino’s characters consistently react to their surrounding circumstances creates authenticity. For example, Bobby doesn’t have a sudden epiphany when he tells Helen that they should move out of the city—it’s another form of lashing out. Pacino delivers that line in the same way that he delivers other lines where the audience knows that Bobby is full of crap. The underlying consistency remains stable throughout the performance.

Throughout his career, Pacino has portrayed other characters who have events or circumstances that remove their agency. These characters are often trapped in dire situations. Like with Bobby, we can see consistent threads running through these characterizations, which adds to their believability. Consider his Emmy Award-winning portrayal of the historical figure Roy Cohn in the 2004 HBO miniseries Angels in America. At first glance, Cohn’s circumstances have nothing in common with Bobby’s—he’s a wealthy, powerful, crooked lawyer. His world changes when he’s diagnosed with AIDS.

What underlies these two performances is that undercurrent of consistency. Bobby lashes out aimlessly. Cohn desperately tries to regain control.

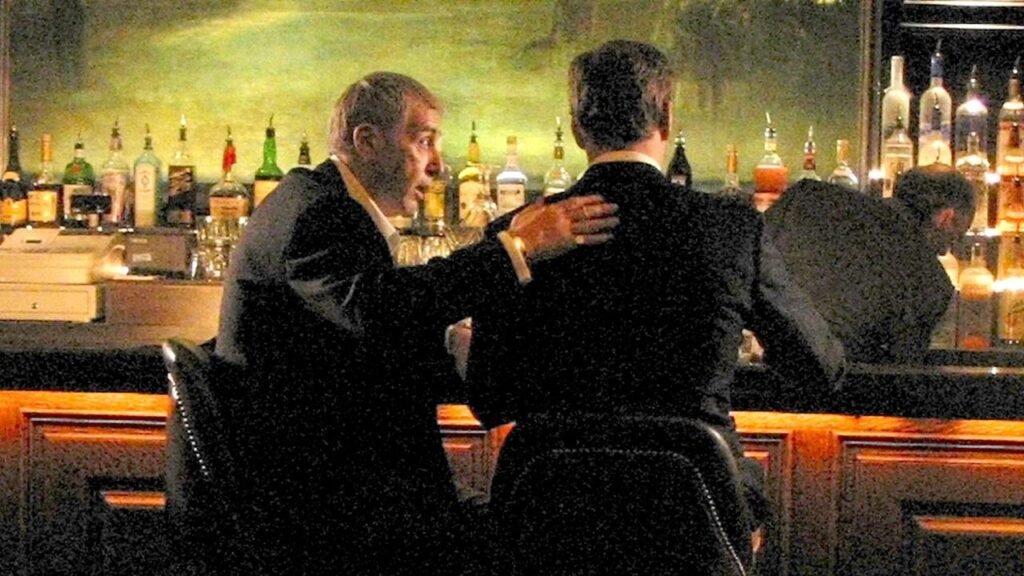

When we first see Cohn, we see a man of action. He’s on the phone in a Manhattan high rise, making moves. The real Roy Cohn was a dangerous and powerful man. During the scene in which Cohn finds out he has AIDS, he immediately tries to bully the doctor (James Cromwell) into staying quiet. It’s a great scene, as both Cromwell and Pacino are legendary actors and watching them spar is a treat.

But like Bobby’s undercurrent of pathetically lashing out, Cohn has his own undercurrent. He’s the master of the universe. He’s not a homosexual, he tells the doctor, those people don’t have power. He has power. The consistency isn’t in the power plays though—it’s in the constant bargaining to maintain that power. Even when he’s hallucinating on his deathbed, he’s bargaining with the ghost of Ethel Rosenberg (Meryl Streep), then takes great pleasure in imagining that he tricked her.

Perhaps, like a wealthier, more powerful version of Bobby, Cohn is quite pathetic too. Even on his deathbed, he hallucinates using his power to lash out at a long-dead foe. Yet, when Ethel’s ghost disappears, Cohn is left with nothing to do but die, like Bobby can only whimper in the aforementioned bedroom scene. Even so, this similarity is only surface-level. The underlying, consistent thread that makes these characters believable is how they react to being trapped in their respective circumstances. Cohn is trying to regain control of his life; Bobby never had any control of his to begin with.

These are only two examples of how Pacino’s performance in The Panic in Needle Park contains elements of his later performances. It’s the beginning of an actor developing his considerable skill set—one that resulted in dozens of memorable performances over the last 54 years. Other examples include how Pacino establishes a character arc, how he switches emotional gears in the same scene, or how he establishes a character’s sense of paranoia. Check out The Panic in Needle Park at the Trylon on June 11th as part of Bleak Week and you’ll see more of what I mean.

Edited by Finn Odum