| John Costello |

Star Wars plays at the Trylon Cinema from Friday, June 13th, through Tuesday, June 17th. For tickets, showtimes, and other series information, visit trylon.org.

Dear H.,

I’m writing you about a work featuring a bold woman, a man with a fast vehicle, and an ominous edifice, Jane Austen’s Northanger Abbey, in the hope that I can relate your interest in that book to another work. You love the social dynamics of Regency Britain, the close focus on manners and their subversion, and the cheery optimism of youth. The values and lessons of the book you so enjoyed apply to the movie of my youth. Hear me out, my young friend.

As a teenager, you walked out of a film—Attack of the Clones, I thought—because the whiny main male character bored you. The main female actor delivered a dead-eyed performance, likely the fault of the director. The acting was stiff, and there was no sense of social decorum or verbal jousting.

I think you would like a film featuring a young woman and young man who are brave and, in Austen’s words, “moreover noisy and wild,” like Catherine Morland in Northanger Abbey (Austen 2021, 4). They argue their cause and snipe verbally, turning sly when it suits their purpose. They also show the boldness of a young woman sneaking through the shut-off parts of an abbey to uncover a mystery.

I tell you now what I didn’t tell you when you first mentioned rejecting the film franchise: Begin at the beginning.

Her Chief Profit Was in Wonder

In Star Wars (1977), a bold and noisy young woman, Leia, plays a central role. The other youth, Luke, forms with Leia a heroine-hero pair. Catherine’s character echoes in both of them. Leia and Luke are at times vulnerable, bold, whiny, and filled with wonder. Both rise to heroic acts in response to the loss of a civility which Catherine ascribes to the “central part of England,” where “there was surely some security for the existence even of a wife not beloved in the laws of the land and the manners of the age. Murder was not tolerated, servants were not slaves” (Austen 2021, 176). Like the novel, the film sidesteps the existence of slavery, displacing the servile role onto robots, called droids.

The quote about security, laws, and manners appears late in the book, after Catherine realizes how her love of Gothic novels has spurred her mind to suspicious flights of fancy. This passage is the closest Austen comes to mentioning the rebellion and wars raging beyond the Midlands during the novel’s composition, from Wolfe Tone’s 1798 Rebellion in England’s principal colony, Ireland to the Napoleonic Wars. If Northanger Abbey is about a reader who reclaims awareness of a rules-based country from her rebellious, novelistic fantasies, Star Wars is about two young people who oppose tyranny and oppose empire.

Our Most Desperate Hour

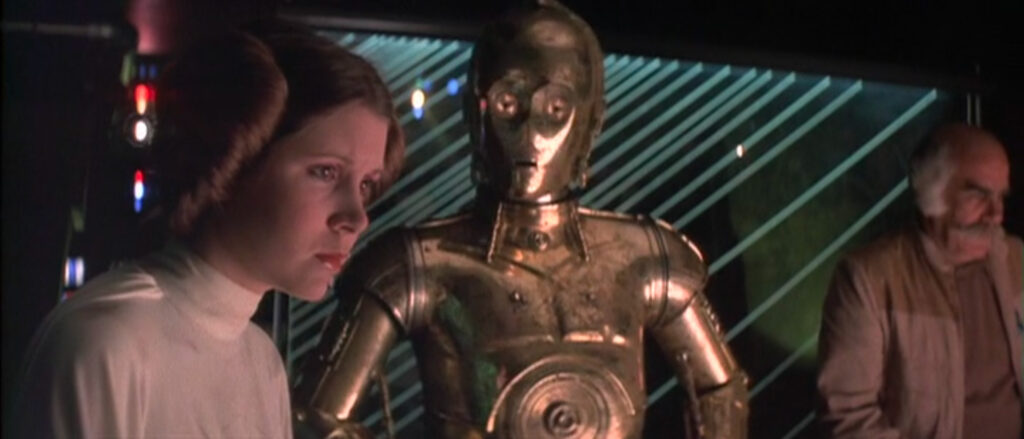

We first see Leia, a teenager dressed in a flowing gown, stooping over a small robot servant tasked with carrying secret plans. She engages in a firefight with three soldiers clad, like the three greatcoat-wearing men who force Catherine into a chaise-and-four, from head to toe in ominous garb. These soldiers are stormtroopers, a name evoking Nazi Germany and Neo-Nazi organizations.

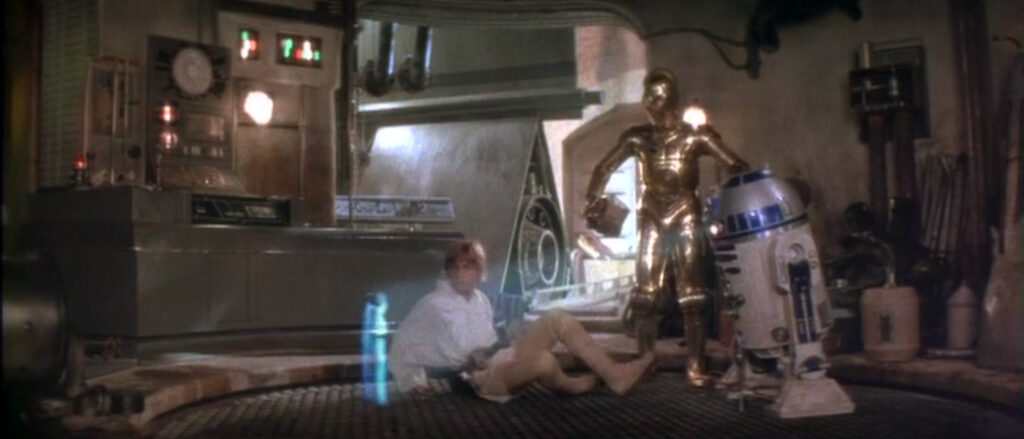

Leia’s droids escape with a message for an old general of great influence, Obi-Wan Kenobi. Where Austen says of Catherine, “Something must and will happen to throw a hero in her way” (Austen 2021, 7), so Leia is thrown in the way of Luke, who discovers part of her secret video message when it is played by one of the droids. (The droids provide comic relief throughout the film.)

Leia displays Catherine’s boldness, as when Morland steals into a bedroom and discovers papers secreted in a wardrobe. Luke shares Catherine’s ignorance and innocence. He dreams about leaving his rural agrarian life on a planet he calls the farthest from the bright center of the universe. He hesitates to go to war, even to rescue Leia or learn more about the father he never knew. (His mother is never mentioned, nor are the parents of any other character.) As circumstances force Leia to ask Obi-Wan for help, so do circumstances lead Luke to follow Obi-Wan.

I won’t try to convince you that Mos Eisley, where Obi-Wan takes Luke to secure passage off-planet, is like Bath. Both towns contain hidden dangers, and each has its share of scum and villainy. In the movie, there is no equivalent to Isabella or John Thorpe, the boastful, inconstant, dissembling siblings. The main movie villains, Tarkin and his thuggish enforcer, Vader, hardly compare to the Thorpes, who would happily betray each other for a battle station and a lightsaber.

The only person who approaches John Thorpe in terms of character is the murderous smuggler, Han Solo. “I defy any man in England to make my horses go less than ten miles an hour in harness,” John Thorpe declares (Austen 2021, 34-35). “She’ll make point-five past light speed,” Han boasts to Luke about his ship. Like Thorpe, Han sings the praises of his vehicle and chases money.

In the search for Leia, Luke is praised and encouraged by the general, who quickly becomes a father figure and abruptly abandons him at the ominous edifice. The Death Star. Like Northanger Abbey, the Death Star is a maze of passageways. Unlike the forcibly disbanded abbey, the battle station’s death and destruction are present, not historic. The Death Star threatens greater danger to the rebellion than Catherine imagines “Italy, Switzerland, and the south of France … as fruitful in horrors” pose to England (Austen 2021, 176).

It’s a Wonder You’re Still Alive

When Luke finally reaches Leia, she takes charge, fighting with the others toward escape, sometimes too hastily. (She and Han both share some of John Thorpe’s brashness, although they are generally more honest.) Leia shouts commands, shoots stormtroopers, and understands better their situation than her companions.

As Catherine struggles against her era’s social maneuvering and the connivance surrounding marriage, Leia fights for respect as a commander. Hers is a second-wave feminist struggle, seeking equal footing with men in fighting while also being entangled in expectations of femininity. Twice, she kisses Luke for luck, and at one point, she provides nurturing comfort for the death of someone who surely meant more to her than the bereaved. (Beyond representations of femininity, the movie’s portrayal of two species of desert-dwelling humanoids, Jawas and Sandpeople, is problematic in other ways.)

Yet, Leia appealed to women and girls I knew. My oldest female cousin often repeated Leia’s mocking command, “Into the garbage chute, flyboy,” usually when she wanted her younger cousins to get into her car faster. Leia projects a strength that was slowly becoming more common in movie heroines of that era.

Catherine and Leia are, in their ways, feminist icons. They are brave women who act against expectations. Their agency and defiance give them a complexity Luke doesn’t gain until several movies later, in part because he acts according to a set of expectations rooted in history, the history of the Jedi and his father.

Delivering to Luke his father’s lightsaber, Obi-Wan says, “An elegant weapon for a more civilized age. For over a thousand generations, the Jedi Knights were the guardians of peace and justice in the Old Republic.” Obi-Wan could be describing Catherine’s belief in that secure central part of England. Except rebellion and empire have spread to the farthest reaches of the galaxy.

Leia, a Princess, subverts one ideal of princesses and embodies leadership. Luke trades the expectation of farming for the expectation that he will become like his father.

Naturally They Became Heroes

I took the header for this section from Leia’s quote in the prologue of my 1977 paperback Star Wars novelization (Lucas 1977, 2). I’ll note that the novelization’s full title, Star Wars: From the Adventures of Luke Skywalker, doesn’t match the original movie title or later revisions to the movie’s title. While Leia is a hero for smuggling the stolen plans, she’s more of a leader, thinking quickly and strategizing how to achieve the concrete goal of defeating the Empire, than Luke, Han, or Obi-Wan.

She consoles a lost-looking soldier about to fly into hopeless battle. Arguing with Han, she shows more knowledge of Imperial methods than his boasting supposes. When threatened with execution, Leia harangues her captors, telling them, “The more you tighten your grip, Tarkin, the more star systems will slip through your fingers.”

During the final battle, Leia remains at the rebel base, her defiance and brashness muted. I like to imagine that she was strategizing with the other leaders, but this notion might be expecting too much from the era. The vast franchise later explains the ways her importance exceeds Luke’s. Even with her muted role, in this film it is clear that she leads the rebellion in ways Luke never will.

Yet Luke injects hope into the rebellion.

It Is a Period of Civil War

It doesn’t matter which version of the film you see. The original 1977 version of the film is less cluttered than later revisions, which paste in extra details and attempt to update special effects, now already outdated. Watching the original movie captures a moment in film history, the way the technology represented an advance for the era. There’s something amusing and authentic about the 48-year-old special effects, the visuals in balance with the orchestral soundtrack. Yet, even considering later adjustments, all versions of the film impart the same excitement and wonder.

The title is Star Wars. Sit back with your popcorn and pretend there is no history, lore, or endless explanations of minor details in the movie. The villains speak with English accents because the American Bicentennial has recently celebrated independence from Britain (declared a year after Jane Austen’s birth), and the English are briefly both distant historic enemies as well as our allies of living memory in the victory over Nazism (it made sense at the time.) You’re a kid seeking adventure and role models for late teenagerhood, and you are also an adult, one shrewd enough to understand the film’s political context.

Instead of the realm of history, the original Star Wars takes you into the realm of fable, a force kindred to what sustains Catherine Morland as she navigates fast vehicles, haunted buildings, and threats to civilized living. In the film, people in the wrong place find each other and achieve a kind of hope against the raw destructive power of technology. Looking to the past (“Long, long ago” the film declares at the beginning) can enable optimism about the future.

I hope you enjoy the movie.

Much affection,

J.

References

Austen, Jane. 2021. Northanger Abbey. New York: Union Square & Co. The header “Her Chief Profit Was in Wonder” is taken from p. 128.

Lucas, George. 1977. Star Wars: From the Adventures of Luke Skywalker. New York: Ballantine Books. The title phrase is taken from p. 2, where the source is named “From the First Saga, Journal of the Whills.” The header “Naturally, they became heroes” is taken from Leia’s quote, also appearing on p. 2.

The other three headers are taken from Leia’s dialogue in the movie and the film crawler itself.

Edited by Olga Tchepikova-Treon