| Devin Bee |

Raiders of the Lost Ark plays in glorious 35mm at the Trylon Cinema from Friday, July 11th, through Sunday, July 13th. For tickets, showtimes, and other series information, visit trylon.org.

During his brief retirement from directing movies—between Behind the Candelabra (2013) and Logan Lucky (2017)—Steven Soderbergh was doing some of his most exciting work. He acted as director, editor, cinematographer, and primary camera operator for all 20 episodes of The Knick, a Herculean undertaking and perhaps the most dazzling filmmaking of his career. He also performed the latter three duties on Gregory Jacobs’s Magic Mike XXL, a film whose luscious cinematography is remarkably attuned to the interplay of lighting and skin tone.

Soderbergh started a blog during this time as well, using it as an outlet for all manner of cinema-related items. The most fascinating of these is a series of posts from 2014, in which he shared experiments he’d conducted with other filmmakers’ work: a mash-up of Hitchcock’s Psycho and Gus Van Sant’s shot-for-shot remake, a 106-minute cut of Michael Cimino’s Heaven’s Gate (Cimino’s preferred version is over twice that length), and a silent, black-and-white version of Steven Spielberg’s Raiders of the Lost Ark.

The first two of these projects are works of clear authorship. That is, Soderbergh has taken existing material and refashioned it to create new films, related to but distinct from their source material.

What he’s done with Raiders of the Lost Ark seems, on first blush, much less intriguing. It’s pedagogical rather than artistic: Soderbergh has merely removed the sound and color to accentuate Raiders’s masterful staging and editing, his only addition a score meant “to aid you in your quest to just study the visual staging aspect.” Soderbergh’s Raiders, then, is not meant to stand alone, but to enhance appreciation of the original.

This seemingly dry academicism is partially why I never watched Soderbergh’s version back when he initially posted it.

The other reason is that I have no affection for Raiders. In my formative years as a film lover, I developed opinions that could generously be deemed skeptical of Steven Spielberg and outright hostile toward George Lucas. I won’t enumerate what are fairly shopworn grievances about the work of both. But in short, I crave friction in art, and their films go down too easy. While my tastes have evolved significantly over the years, my prejudices toward Spielberg and Lucas remain sturdy. The collaboration of both on Raiders is largely the reason I’ve not revisited the film in nearly 20 years.

But in light of Raiders coming to the Trylon, coupled with my distaste for uninterrogated intransigence, the time seemed ripe to participate in Soderbergh’s Raiders exercise. I was curious: how would it play for a viewer with only vague impressions of the original?

As mentioned above, Soderbergh wants his version of Raiders to highlight the staging, which he roughly defines as “how all the various elements of a given scene or piece are aligned, arranged, and coordinated.” In this respect, his version is a resounding success. With the film stripped down to its basics—no quippy dialogue, no iconic score, no warm, earthy color palette, no granular plot details—the fluidity and coherence of the visual storytelling come to the fore. Save for a few scenes of expository dialogue (and even in those the tenor is clear), you always know exactly where you are and what’s happening. All aspects of a given image gracefully work together to guide your eyes where to look. Appearance and performance individuate each character, and the dynamics between characters quickly become clear. Every shot and scene has been sequenced and visually constructed to flow seamlessly from one to the next. Add a few title cards and Raiders functions beautifully as a silent film. Reaction shots often even have a distinct silent-film flavor, with characters posed tableau-like, faces frozen in exaggerated expressions of emotion. None of this comes across as hand-holding; visual elegance just characterizes every aspect of the storytelling.

But the pleasures extend beyond those aspects of the original that are thrown into relief. If Soderbergh wanted to create the conditions to “just study the visual staging aspect,” perhaps he should’ve removed the sound and left it at that. By turning the film black-and-white and, more crucially, adding new music, Soderbergh has performed a bit of alchemy.

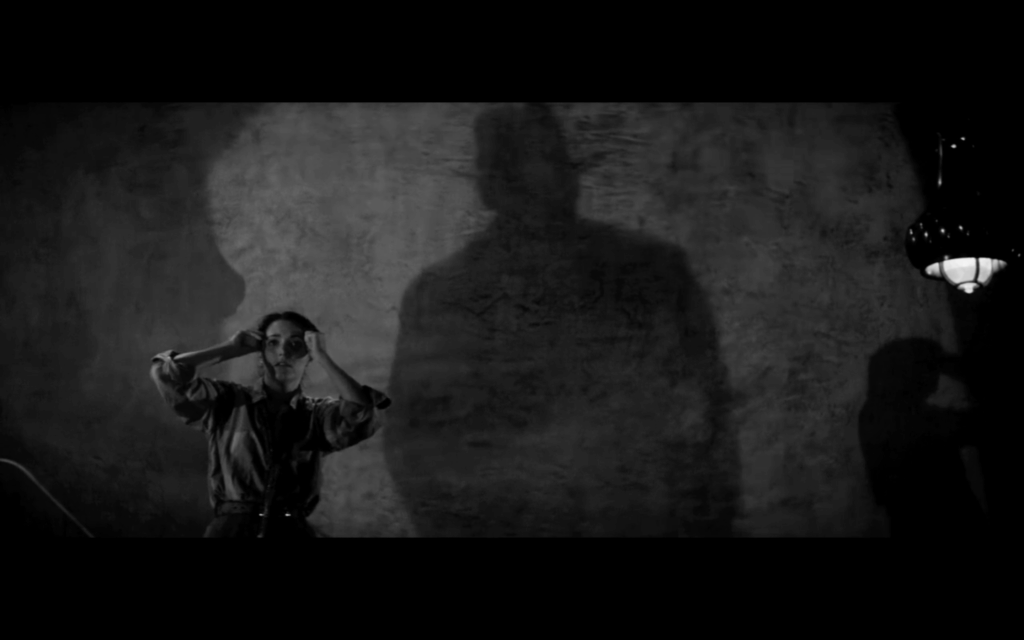

Light and shadow conspire to produce powerfully expressive monochrome images—stygian blacks, smoky grays and whites, sparkling beads of water on flesh. But a transformation occurs that transcends surface appearance. With the stark chiaroscuro accentuated, and the story’s complementary dialogue and music removed, the film’s tone shifts. Raiders starts to seem less like a breezy swashbuckler and more like a horror film. The darker qualities—both literal and figurative—become more prominent: the shadowy figures lurking about; the smoke, fog, dust, and sand obscuring what the eye can see; the skeletons and decomposing corpses; the spiders and snakes; the gore; the thunderbolts, bright and jagged, cutting paths through a sky of turbulent dark clouds. Even our hero, Indy (Harrison Ford), cuts a slightly sinister figure—frequently materializing out of darkness; casting a monstrous shadow on the wall over Marion (Karen Allen) in their first shared scene (an image that disquietingly rhymes with the entrance of a gang of Nazis minutes later). With the horror elements emphasized, it only seems natural that the film climaxes with an army of angry spirits unleashing carnage on those who played with forces they didn’t understand.

But it’s the use of music that transforms Soderbergh’s version into something alien. It’s the first thing you notice, bursting out of the silence and a black screen: a pulsing, four-on-the-floor beat and crunchy, alternating synth notes. A thick sonic texture gradually builds—an ascending run of rapid-fire bleeps and bloops, syncopated ticking, a spare, ghostly melody, and myriad other electronic elements. The soundscape is radically different from John Williams’s famous Raiders score. It is, rather, “In Motion”—a piece composed by Trent Reznor and Atticus Ross for The Social Network. In fact, Soderbergh has set the entirety of his version of Raiders to Reznor and Ross’s music, drawing not only from their score for The Social Network but also The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo.

The music is anything but neutral; music worth its salt never is. And it’s not as if Soderbergh has chosen music—like the ambient works of Brian Eno—designed for background submersion (though that would have produced its own interesting effects). He’s chosen some of the most striking film music from the twenty-first century, music that creates unique moods and textures when combined with the black-and-white images of this rendition of Raiders.

One effect is that the ever-present music and its emphasis on rhythm amplify the musicality of the film’s visual movement. The camera, bodies, and objects in motion combine with the editing in a narrative dance. The action and fight scenes in particular move with an inventiveness and rugged grace that makes me vibrate with giddiness.

And it’s in the use of music—the one addition in an experiment of subtraction—that Soderbergh can’t repress his filmmaking instincts. The clearest evidence of this is that the music starts and stops in alignment with the film’s visual rhythm—at the beginning or end of a scene or at some other point of transition, like a significant cut or a shift in tenor or pace. It also seems, in each instance, that Soderbergh has considered: which piece of music will interact with the images in interesting ways? What will yield striking resonances? Sometimes this results in a little chime between sound and image, as when a fight beside a running airplane is accompanied by music featuring a sound like a sputtering propeller. Sometimes it’s the pleasant familiarity of a reprise. Frequently, it’s a moment when the black-and-white picture, Spielberg’s filmmaking, and the music of Reznor and Ross combine to induce a trance-like state, a powerful aesthetic experience unique to this version of the film.

Soderbergh’s Raiders accomplishes what it sets out to do. It’s hard to imagine coming away from it without a newfound appreciation of Spielberg’s craft, his undeniable virtuosity. But it’s much more than the didactic exercise Soderbergh presents it as. It’s like a good remix, harnessing core features of the original to create a new experience, one that reflects on its source but has a potency all its own. So, yes, I certainly want to return to Spielberg’s original. But right now all I can think about is Indiana Jones in stunning black-and-white, moving through shadows to the sounds of fat synths, industrial wails, and spare piano figures.

Edited by Olga Tchepikova-Treon

Now I wanna see Soderbergh Indy.