| Dan McCabe |

Julie Andrews in The Sound of Music (1965). If you’re like me, this image immediately begins playing “The Hills Are Alive…” in your head.

The Sound of Music plays for one day only at the Heights Theater on Sunday, July 20th, as a collaboration on our Nazis…We Hate These Guys! series. For tickets, showtimes, and other series information, visit trylon.org.

I recently visited New York, and as I walked along West 45th Street through its famous theater district, I couldn’t help but imagine the marquees that came and went from the Great White Way over the last century. One such show, opening in 1959, was The Sound of Music, which, of course, became the source material for Robert Wise’s 1965 film of the same name. The Sound of Music on stage won five Tony Awards, and the film version symmetrically won five Oscars.

From Rodgers and Hammerstein’s acclaimed final show to the highest-grossing film of the 1960s, The Sound of Music followed a familiar path in the middle of the twentieth century. Between 1955 and 1972, ten Best Picture nominees and four winners were adaptations of Broadway book musicals. The lists of the highest-grossing films of those three decades include numerous such adaptations including South Pacific (1958), My Fair Lady (1964), and Grease (1978).

Imagine the development of motion picture technology on one train track, taking you from the advent of sound to color to modern special effects. Then, imagine another track, only this one following the artistic development of the Broadway musical from the musical revue to the book musical to the boundary-pushing shows of the 1970s and 1980s. You’ll see these lines run parallel during the middle of the twentieth century, but start to diverge around the 1970s.

The Waltz of the Shadows in Gold Diggers of 1933 is an example of the spectacle of early Hollywood musicals.

1920s to 1940s

Let’s go back to the beginning. Before the advent of sound in movies, Broadway musicals and Hollywood did not have a strong connection. That’s not to say that there was no connection between theater and film before sound; after all, legends like Charlie Chaplin and the Marx Brothers began their careers on stage. But with no sound, the fledgling film industry had no need for songs or singers. That all changed in 1927, when one of Broadway’s biggest stars headlined Warner Brothers’ The Jazz Singer (1927) and forever changed the development of the motion picture.1 Overnight, the demand for music, musicians, and singers in the film industry went through the roof.

Meanwhile, Broadway was going through its own transition. From the late 1890s through the mid-1920s, revue musicals like The Ziegfeld Follies and vaudeville shows dominated the New York theater scene. This began to change the same year that Hollywood began the transition to sound. Showboat (1927), written by Jerome Kern and Oscar Hammerstein and produced by Florenz Ziegfeld (of the famous Follies), is considered the first “book musical.”2 Unlike revue musicals, which relied on a series of unrelated song and dance numbers to keep audiences engaged, the book musical followed a central story.

Showboat and its successors such as Anything Goes (1934) and Pal Joey (1940) created a talent and content pipeline for motion picture studios hungry for big song and dance spectacle. Ginger Rogers, for example, made her Broadway debut in the Gershwins’ early book musical “Girl Crazy” in 1930, and within a few years was one of Hollywood’s biggest stars. Hollywood also began to copy the “book musical” format during this time in films such as Gold Diggers of 1933 (1933) (starring none other than Ginger Rogers).

The ballroom from The Sound of Music is an example of the elaborate set designs that studios had no problem paying for during the peak of the Broadway to Hollywood pipeline.

1940s to 1970s

While you can set apart the musicals of the 1920s and 1930s from the revue format, these shows often had light or non-existent plots and musical numbers that had little reason for being there aside from entertainment value. There’s not anything wrong with this per-se—after all, musicals such as Anything Goes get revived to this day.3 That said, Oklahoma! (1943) is considered by many the first modern musical.4 Rodgers and Hammerstein developed this show differently than their previous shows with other collaborators (Lorenz Hart and Jerome Kern respectively). Oklahoma!, and subsequent Rodgers and Hammerstein musicals like The Sound of Music (1959) followed a simple rule: no song or dance numbers for their own sake. Everything needed to advance the plot or the development of the characters. At first, this approach was looked at as folly,5 but Oklahoma! was a triumph, running for a then-record 2,212 performances.

It’s hard to overstate Oklahoma!’s overnight influence on Broadway, but in contrast, the major development on the other coast was more gradual. Slowly, the motion picture studios began to release color films. The Technicolor process was not cheap, and was often reserved for surefire hits during this period. Now, you might be thinking, what does this have to do with the Broadway musical? Well, look at the film adaptations of the Broadway musicals in between 1955 and 1975, and you will notice something. They are nearly all shot in rich Technicolor.

Got a hit Broadway show? Great! You have a script, set pieces, even a cast in some cases that the studios could simply lift from New York, shoot in color on a soundstage, and watch the money roll in. When these productions began getting Oscars, that justified spending even more on production value. Open a film with establishment shots of the Austrian Alps that probably cost a fortune to get? Why not? You’re only making the most popular film of all time up until that point: The Sound of Music.

Now, you might think, “How could 20th Century Fox know that The Sound of Music would be a monster hit?” The award-winning swan song of Rodgers and Hammerstein starring newly-minted Oscar winner Julie Andrews? Even if the movie wasn’t great—and it is truly a capital “G” great film—it would have printed money for the studio. That was the power of the Broadway musical during the 1950s and 1960s. As the most successful example, The Sound of Music represents the cultural, commercial, and quality apex of the mid-century Broadway to Hollywood pipeline.6

Liza Minnelli in Cabaret (1972). Cabaret was the last musical nominated for Best Picture until Chicago (2002).

1970s to 2000

So what happened? How did this surefire formula for Hollywood success fall apart? What happened on the West Coast is a little easier to explain so I’ll start there. Since the beginning of the sound era, arguably the pinnacle of Hollywood spectacle was the song and dance musical. From the “big waterfall” number in Footlight Parade (1933) to the symphonic dances in West Side Story (1961) to those alive hills in The Sound of Music, the “big number” represented “movie magic.” That is, until a menacing shark (Jaws, 1975) and a galaxy far, far away (Star Wars, 1977) hit the screen. Special effects began to mean making the fantastic seem real, and no longer meant hundreds of singers and dancers. In other words, changing technology and changing tastes caused Hollywood to make fewer big budget musicals.

Broadway changed during these years as well. Broadway moved towards more experimental theater that wasn’t as easily translatable to film like the Rodgers and Hammerstein shows of the previous era. For example, A Chorus Line (1975) and Cats (1981)—two of the most successful shows of between 1970 and 2000—resisted successful adaptation. Indeed, attempts to make films based on these shows were commercial and critical failures in 1985 and 2019 respectively. Other successful shows such as Sweeney Todd (1979) had subject matter that kept them off the screen for decades.7

Broadway itself had its share of problems during this time as well. New York City suffered through a brutal economic downturn in the 1970s and 1980s and the famed “Great White Way” of the previous decades suffered for it in terms of safety and reputation. Tragically, the AIDS crisis also hit Broadway hard during this period, taking a generation of talented artists. It’s no coincidence that the many of the most popular shows of this period came from Europe rather than New York (e.g. The Phantom of the Opera (1986), Les Miserables (1985)).

As a result, the popularity of musical theater faded. It could no longer lay claim to the dominant cultural force it possessed in the 1950s and 1960s. Hollywood could no longer justify throwing gobs of money at Broadway adaptations. At least not until the current century.

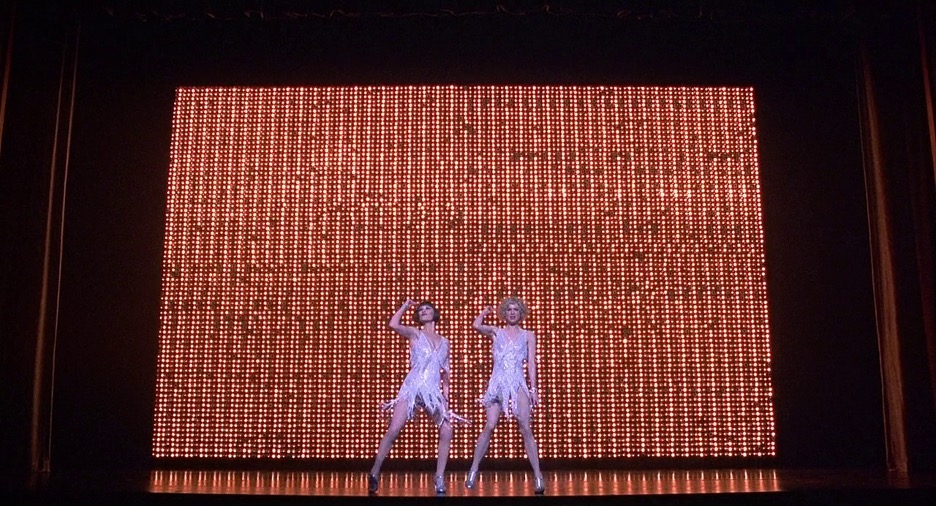

Renee Zellweger and Catherine Zeta-Jones in Chicago. Chicago won Best Picture at the Oscars and began a revival of notable Hollywood adaptations of Broadway musicals.

Broadway’s fortunes began to improve with the New York City economy in the 1990s. While musical theater never regained the kind of cultural power it had in the days of Rodgers and Hammerstein, an improved image of Broadway itself may have justified studios taking chances on more frequent adaptations. Chicago winning Best Picture in 2002 certainly helped, and even so-called “unadaptable” shows like Sweeney Todd and mega-productions like Wicked (2003) and Les Misérables got their turn to shine on the big screen. There are even examples of musicals adapting films, and then another film adapting that musical.8

While the Broadway-to-Hollywood pipeline is certainly back in working order, none of today’s adaptations can lay claim to being the critical, commercial, or cultural masterpiece that is The Sound of Music. There’s a reason ABC plays it every year around the holidays. My Favorite Things? Definitely not a Christmas song, but The Sound of Music’s association with the holiday season is so powerful that it commonly appears on Christmas albums. That said, it is a wonder to see it on the big screen, which I was fortunate enough to experience a decade or so ago, and you can watch it on July 20th at the Heights Theater in Columbia Heights. If you do, you can think about it as the pinnacle of a time when adapting successful Broadway musicals was a surefire hitmaker for Hollywood.

Footnotes

1 The Jazz Singer is notable as the first sound film, but Al Jolson’s blackface performance renders the film unwatchable.

2 Musicals: The Definitive Illustrated Story. (Dorling Kindersley, 2021), p. 14-17.

3 The 2011 Broadway revival of Anything Goes won the Tony for Best Revival of a Musical.

4 Musicals: The Definitive Illustrated Story. (Dorling Kindersley, 2021), p. 58-61.

5 Walter Winchel, the famous newspaper columnist, sent one of his staff to review the previews of Oklahoma! The staffer curtly summarized the show as “no legs, no jokes, no chance.” Ibid. p. 58.

6 When adjusted for inflation, The Sound of Music is the third highest-grossing film of all time in the United States.

7 Sweeney Todd is one of Stephen Sondheim’s masterpieces. It also has a song where the main characters gleefully discuss stuffing the remains of their murder victims into pies. Rodgers and Hammerstein it is not. It was finally adapted into a film in 2007.

8 Examples include The Producers (Film 1967, Musical 2001, Musical Film 2005) and Mean Girls (Film 2004, Musical 2017, Musical Film 2024).

Edited by Olga Tchepikova-Treon