| Dan McCabe |

Herzog’s The Dark Glow of the Mountains (1985) concerns itself with the spirit of mountain climbers, not just filming their exploits. It is part of the 45-Minute Documentaries of Werner Herzog playing at the Trylon from August 8th through 10th.

The 45-Minute Documentaries of Werner Herzog play at the Trylon Cinema from Friday, August 8th, through Sunday, August 10th. For tickets, showtimes, and other series information, visit trylon.org.

In 1999, acclaimed German filmmaker Werner Herzog came to the Walker Art Center for an on-stage interview with the late film critic Roger Ebert. During the interview, Herzog made his “Minnesota Declaration”—a twelve-point denunciation of Cinema Verité, a style of documentary that aims to film reality as-is with little visible interference from the filmmaker.1 “There are deeper strata of truth in cinema, and there is such a thing as poetic, ecstatic truth. It is mysterious and elusive, and can be reached only through fabrication and imagination and stylization,” Herzog said. The documentarian should not limit themself to the artificial conventions of Cinema Verité. Herzog calls this theory Ecstatic Truth.

Dziga Vertov, here in a photograph taken by his brother and cinematographer Mikhail Kaufman. Kaufman is the “Man with a Movie Camera” in the film of the same name.

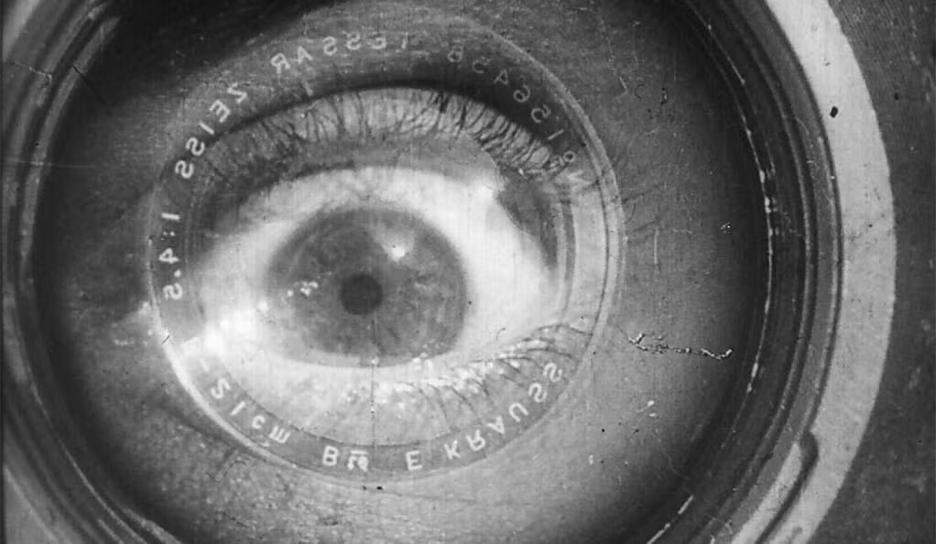

The idea of Cinema Verité comes from a French translation of “Kino-Pravda,” the name for a groundbreaking series of short, silent documentary films made by Soviet filmmaker Dziga Vertov in the 1920s. Both terms roughly translate to “film truth” in English. The foundation of the concept is Vertov’s earlier theory of the Cine-Eye. “I am the Cine-Eye. I am the mechanical eye. I the machine show you the world as only I can see it. I emancipate myself henceforth and forever from human immobility. I am in constant motion… My path leads towards the creation of a fresh perception of the world. I can thus decipher a world that you do not know,” Vertov wrote in 1923. Vertov believed that the camera could illuminate truths that the human eye could not see, and that the camera should be allowed to do its work, free from the structural conventions of literature or the spectacle of theater.

The French theorists, inspired by Vertov,2 set forth the ground rules of Cinema Verité, and generally defined it as a filmmaking style in which the audience is unaware of the filmmaker’s presence (although they may be aware of the camera’s presence). Films in this category often contain little or no voiceover. If there are interviews, the audience usually doesn’t hear the questions. The filmmaker takes themselves out of the story as much as possible. The idea is that taking away the hand of the director illuminates the truth.

Herzog believes this to be nonsense.

There we have two important filmmakers standing on opposite ends of the twentieth century with seemingly opposing views of what makes an effective documentary film. But was Herzog truly rejecting Vertov’s theory of the Cine-Eye? Or was he simply providing a more expansive definition of what a documentary could be if a filmmaker used all tools at their disposal? Are the theory of the Cine-Eye and the theory of Ecstatic Truth so far apart?

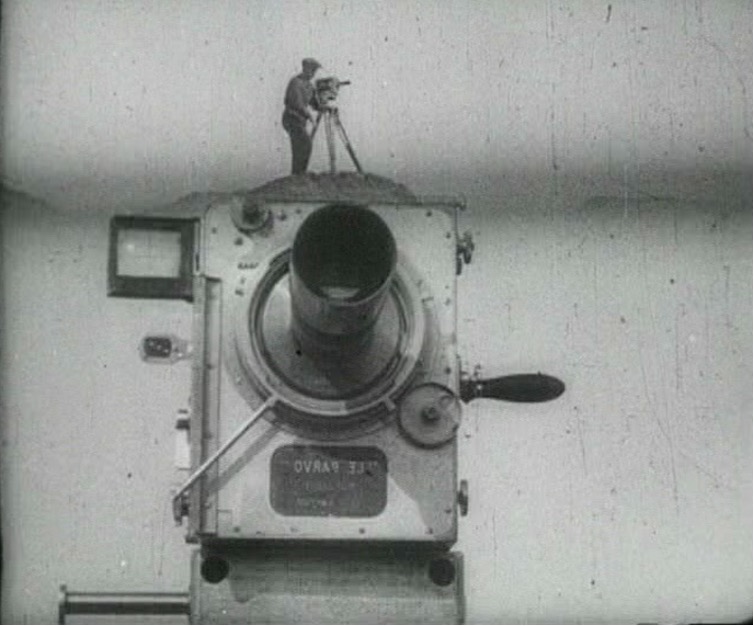

This split-screen image from Man with a Movie Camera makes it appear as if Mikhail Kaufman is shooting the film from the top of a giant camera. It is one of many innovative shots from the film.

The name Dziga Vertov echoes across the decades for those interested in the history of the motion picture, but he remains quite a mystery. His career peaked a century ago, making movies either for, or sanctioned by, the totalitarian Soviet regime. Some of his early films are lost, and much of what exists of the rest of his work remains inaccessible. You won’t find the Kino-Pravda series (1922) on streaming services, for instance. Despite these obstacles, his film Man with a Movie Camera (1929) has been the highest-ranked documentary in the Sight and Sound polls for 2012 and 2022.

Man with a Movie Camera lives up to its reputation as a groundbreaking documentary. Vertov included jump cuts, dissolve transitions, fast and slow motion, split screens, double exposures, and more: some of the earliest examples of these types of shots. It’s a one-hour summary of the anatomy of the moving image. At a time when movies had an average shot length of over 10 seconds, its shot length clocks in at just over 2 seconds, equivalent to modern blockbusters.

It took Vertov and his team four years and three different cities (Moscow, Kyiv, and Odesa) to create his idealized day in a 1920s Soviet city, so there is some artifice to the film. In contrast, one of my favorite Cinema Verité style documentaries is Barbara Kopple’s Harlan County, USA, which documents a single coal miners’ strike from start to finish. Does this mean that Man with a Movie Camera doesn’t qualify as Cinema Verité? Hardly. Even if Vertov’s “one day in a single city” is in truth a mosaic of three cities over several years, I don’t think that detracts from Vertov’s stated purpose. He was creating something new: a documentary film without a “script;” one entirely separated from the conventions of the stage, seeking deep truth. Contrast that to his contemporary, Robert J. Flaherty whose Nanook of the North (1922) was notoriously scripted.3

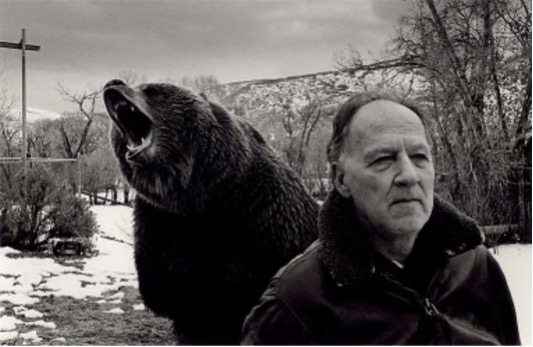

Werner Herzog filming Cave of Forgotten Dreams (2010), a key example of his theory of Ecstatic Truth in action. In the film, Herzog imagines the artistic intent of anonymous artists who lived 30,000 years ago.

One can assume that, as a director of both narrative and documentary films, Herzog does not share Vertov’s disdain for the conventions of theater and literature. He purposely injects story and artifice into his documentaries. In Cave of Forgotten Dreams (2010), Herzog used 3D cameras to emphasize the intent of the artists of the Chauvet Cave in Southern France. Herzog is merely speculating at the aims of these artists, who lived 30,000 years ago.

Here, in a cave so fragile that Herzog could only film it for a couple of days, you can see his vision of “Ecstatic Truth” in action. I left the film aware of the spirit of these cave-dwelling painters who lived before the Agricultural Revolution, even if that spirit only exists in Werner Herzog’s brain. There’s a reachable, common truth in art, and if Herzog sought to illuminate that truth, he succeeded.

A promotional still from Grizzly Man (2005). Throughout the film, Herzog is baffled by his subject, and makes that entirely clear to the audience. Interestingly enough, this is the same kind of split-screen image that Vertov pioneered in Man with a Movie Camera.

Another example of Herzog’s “Ecstatic Truth” in action comes from Grizzly Man (2005). If a key tenet of Cinema Verité is the removal of the filmmaker’s hand, Grizzly Man sits at the opposite end of the spectrum. From the very first shot, Herzog’s voiceover makes clear that he finds his subject, late bear enthusiast Timothy Treadwell, either foolish, insane, or both. Herzog presents a man who thought he was friends with bears and got eaten by one with the tinge of “what exactly did he think was going to happen?” Imagine something like The Beatles Anthology (1995) with a voiceover stating “of course these talented artists were destined to have a bitter breakup,” and you have Herzog’s voiceover in Grizzly Man.

Herzog absolutely has a point in his Minnesota Declaration. The filmmaker’s hand is never absent from a documentary. They select the subject, they frame the shots, they compose the order. Harlan County, USA tells only the coal miners’ side of the story of the strike. The film includes the old labor anthem, Whose Side are You On?, and it’s crystal clear whose side Kopple was on. The Beatles Anthology tells the story of the band in their own words with no voiceover, but it’s clear that the filmmakers traded access for avoiding certain topics. The Beatles’ bitter breakup, for example, gets very little screen time compared to their nostalgic tales of their early days.

One could counter that the modern nature documentary especially would not be possible with too much hand of the filmmaker. By their nature, other animals view humans as large predators and would steer clear of a film crew if they made their presence known. That, or the film crew would put themselves in danger. The popular BBC Earth series, for example, must rely on the power of the camera to tell its story. However, what would those documentaries be without David Attenborough’s voiceover?

By superimposing images, Vertov created the image of the “Cine-Eye” in Man with a Movie Camera.

Werner Herzog asks that filmmakers use those tools, all of them, without reservation. He is one of the modern era’s most vibrant filmmakers, unbound by convention. His theories of cinema build upon those that came before. He proposes an artform without limitation, documentaries that pursue truth using all the powers of the director and their team. In my view, Dziga Vertov did exactly that.

What is Man with a Movie Camera if not “fabrication, imagination, and stylization?” True, Vertov’s subjects are real people going about their everyday business, but Vertov and his team cut those images in to montages and used double exposure to create new images. He is not simply, as Herzog put it, a “tourist who take(s) pictures of ancient ruins of facts”; he uses the tools of the filmmaker to provoke reaction. He wants the audience in awe of his “ideal city,” and even ninety-six years later, he gets us there.

Dziga Vertov imagined the potential of the Cine-Eye, and through experimentation created a new language of expression. Aren’t we all seeing the world through the Cine-Eye these days? We have the technology in our hand to create endless videos and pictures, but how often do we look back at those videos and pictures? What draws us to the ritual of filming the world around us and either filing it away for later viewing or sharing it in a sea of content? Did Vertov imagine this world when he sought a language for film set apart from the language of theater and literature?

As for me, I think these two great filmmakers touched upon a similar concept: that movies have a unique language and power, and filmmakers should not confine themselves into boxes, whether those structures are created by the conventions of literature and theater or the theories of Cinema Verité. Both believed in the power of film, but especially, film without limitation.

Footnotes

1 The entire interview can be found on the Walker’s YouTube channel.

2 Edgar Morin and Jean Rouch are credited with coining the term in the early 1960s, but “the ground rules” of what it means are often disputed, and different filmmakers have had different definitions.

3 “Nanook” wasn’t even the real name of Flaherty’s subject, and at least one of “Nanook’s” on-screen wives was allegedly Flaherty’s mistress.

Edited by Olga Tchepikova-Treon