| Alex Kies |

The Ceremony plays on glorious 35mm at the Trylon Cinema from Friday, August 22nd, through Sunday, August 24th. For tickets, showtimes, and other series information, visit trylon.org.

Lots of interesting things happen at weddings and funerals. It’s a shame to miss any of it.

– Ritsuko

Although he is a key figure of Japanese New Wave, and his final films were consciously West-facing, Ōshima Nagisa never quite took off in the West like his friend Kurosawa Akira. His work is often so insular and specific to Japanese culture and history a bit of homework is necessary (for me) to fully appreciate. Case in point, his 1971 film The Ceremony.

The Ceremony follows Masuo, Tadashi, Temurichi, and Ritsuko, a group of cousins from the Sakurada ie (family clan) over 25 years. The film begins in the present with Temurichi telegramming the others that he is committing suicide at the old family estate. Masuo and Ritsuko’s journey home is punctuated with protracted flashbacks to key moments of their family lives.

Each of these episodes coincides with a Sakurada family gathering or ritual and corresponds to significant events in Japanese history:1

- 1947—Masuo’s Return Home—Manchurian Repatriation

- 1952—Masuo’s Mother’s Funeral—U.S./Japan Security Treaty

- 1956—Uncle Isamu’s Wedding—The Growth of the Zaibatsu (family-owned private conglomerates, often in banking, construction, shipping, etc.)

- 1961—Masuo’s Wedding—The Renewal of the U.S./Japan Security Treaty

- 1971—Masuo and Ritsuko’s Return Home—The Suicide of Mishima Yukio (whom Ōshima debated and eulogized)2

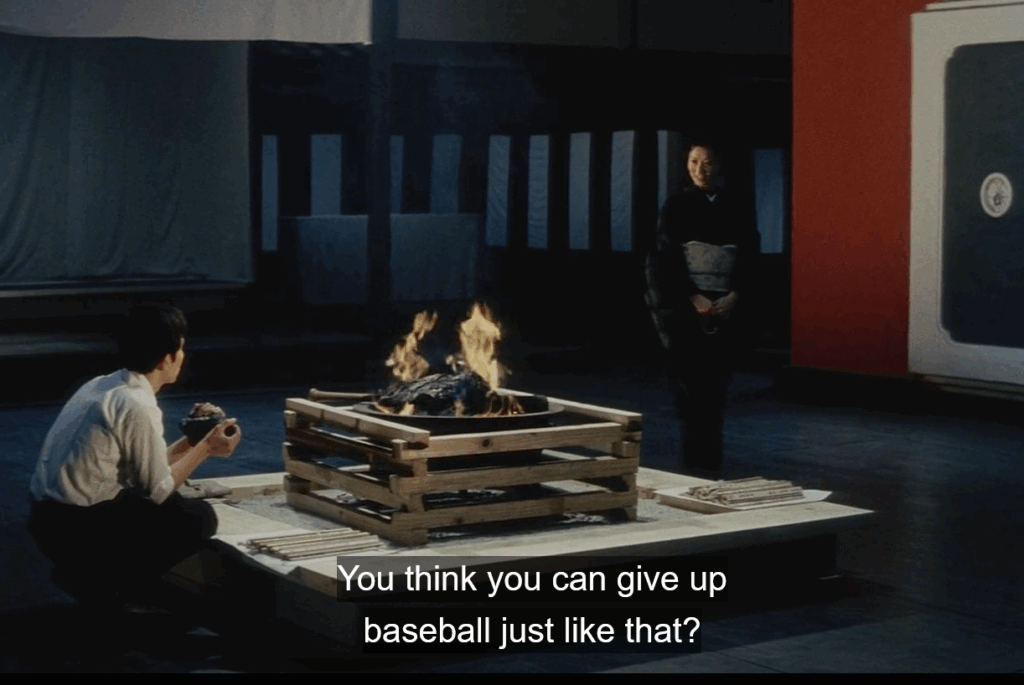

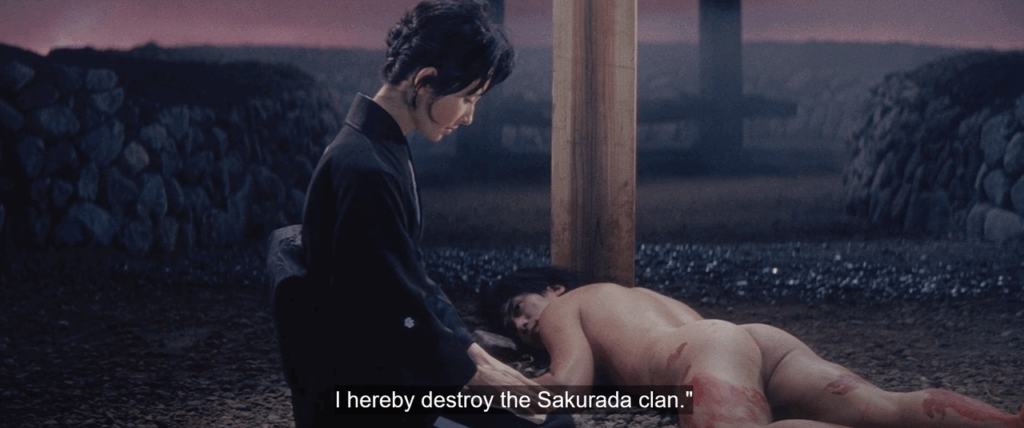

The relationship between these scenes and the real-life events is variably oblique. Masuo and his mother return home from wartime Manchurian exile (Masuo is literally “Man of Manchuria”), icily received back into the ie. While Japan acquiesces to a domestic American military presence, Masuo gives up a home run in a baseball tournament (a Western import) as his mother dies. As the family fortunes soar in the late 50s, Uncle Isamu and his bride sing L’Internationale at their wedding feast. As Masuo is married to an absentee bride for familial considerations, Japan renews its security contract with the Americans. Finally, the climactic suicides of Temurichi and Ritsuko mirror Mishima’s, representing the death rattle of traditional right-wing patriarchal militarism.

As the film ends, Masuo is the survivor and heir to the Sakuradas. For the duration of the film, he’s been buffeted about by the winds of history and the whims of his family, all of whom are externalized representations of this postwar Japanese psyche, all of whom are stripped away or revealed to be illusory. In her excellent (if a bit heady) The Films of Ōshima Nagisa: Images of a Japanese Iconoclast, Maureen Turim explains:

Masuo… is not to be taken as an explanation of the text but as a device within it… [The Ceremony performs a modernist theory] of subjectivity, the divided psyche, the processes of displacement, condensation, and reversal into the opposite, rather than merely representing a character as displaying this psychic state. (112-113)

Masuo’s grandfather is the embarrassed patriarch, a vestige of traditional ie dynamics, holding everything together through intimidation, money, and sexual abuse. Masuo’s father’s will indicates he committed suicide in despair over the Emperor’s renunciation of his divinity. One of Masuo’s uncles, a POW, wrote a denunciation of the Imperial Army in Chinese captivity, but refuses to speak at home. Uncle Isamu’s dialogue rarely transcends Communist sloganeering.

Ōshima, a big Buñuel fan, never provides a coherent explication of anything. The audience of the narration changes from flashback to flashback. In the present day, Ritsuko challenges the accuracy of Masuo’s recollections. Funerals are given without bodies. People are buried alive without funerals. Masuo is married without a bride present. The roles characters play for each other and their relationships change from scene to scene: Masuo’s Aunt Sutsuko assumes a motherly role. Ritsuko is a cousin, sister, and lover for her male cousins. Masuo is “living for” his dead brother, father, and mother. A thrice-recurring flashback of a childhood baseball game (a ritual from the West Matsuo learned in Manchuria) the cousins play umpired by Aunt Sutsuko significantly requires several ghost runners.

But once Masuo casts these associations aside, we find him looking into an uncertain future, unsure of himself, with a great deal of responsibility but no agency.

Ōshima is a singular filmmaker in Japanese history, let alone filmmaking history, in that he didn’t begin making movies because he loved them and had always dreamed of making them:

I joined Shochiku Ofuna Studios as an assistant director in 1954. I wasn’t a film lover; it was just that no other company would hire me, so I happened to end up at a film company.3

He was not content to merely be a filmmaker, either. He fashioned himself into a public intellectual. He wrote for venues from gardening magazines to legal journals. As previously mentioned, he also served as Mishima’s leftist interlocutor (though Ōshima was by that point well-disillusioned with the Japanese Left). He also translated books into Japanese, most notably Men are from Mars, Women are from Venus. He devoted years of his career to directing and hosting television documentaries, which, like his narrative films, often concerned gender relations, people at the margins of society, particularly gaijin—outsiders living in Japan. Masuo is a prime example of one such figure, like Englishmen in Merry Christmas, Mr. Lawrence, homosexuals in Taboo, African Americans in The Catch, Koreans in Death by Hanging, Catholics in Band of Ninja, and French guys who get cuckolded by orangutangs in Max, Mon Amour.

Ōshima deprioritizes entertainment for intellectual stimulation. He eschewed traditional structures and techniques and imposed Oulipian constraints on himself. Famously, for a long time, he excluded green from his films.

A key aspect of his self-conception as an artist showcased in The Ceremony is self-negation, his own little twist on the Auteur Theory. The Auteur, he felt, defies and makes “absolute his ego’s images… renders himself unable to grasp all reality except in the context of those images.”4

In order to create “new films,” the filmmaker must engage in absolute self-negation:

Once a filmmaker has created a work, the method expressive of his active involvement must be thought of as part of his external reality… Only the maintenance of a state of tension between reality and the discovery of a new method of perpetual active involvement will enable him to make works that are a true expression himself.

Thus the filmmaker must always seek a new tension with reality and constantly negate himself in order to continue to create a new artistic involvement.5

Believe it or not, he was a big hit with the French.

But the fascination with effacing the ego and identity that pervades his writing, filmmaking, cannot be completely intellectual. He grew up at the same time and place as Masuo, likewise without a father figure. Ōshima’s essay, “My Father’s Nonexistence: A Determining Factor in My Existence,” (originally appearing in Techniques for General Education two years after the release of The Ceremony) explores growing up after the war without a father, and it’s hard not to read into this passage with The Ceremony in mind:

I am 99 percent submissive to older men and exceedingly courteous. However, the 1 percent in me that can’t possibly be deferential is resolutely rebellious and impolite. It is clear that this behavior works against me in life. Conversely, though, accumulating these handicaps helped make me at least slightly out of the ordinary. Therefore, this behavior pattern, which gets me in trouble, is important in itself, and insofar as my father’s nonexistence was the basis for it, I should probably be grateful for his nonexistence…6

Ōshima’s idiosyncratic perspective led him to found his own production company early on in his career to avoid studio interference. His films were rarely hits in Japan but were well-regarded critically. His final five films, In the Realm of the Senses, Empire of Passion, Max, Mon Amour, Merry Christmas, Mr. Lawrence, and Taboo all deal with the nature of sexual politics. The first three about heterosexual marriages, and the latter two about the homosexual overtones of bushido culture.

In the Realm of the Senses, his first film after The Ceremony, concerns a real-life tale of sexual obsession in the early 1930s, complete with unsimulated sex scenes. The Japanese Government itself brought obscenity charges against Ōshima, which led to a six-year trial. As a result, Ōshima spent much of the rest of his career pursuing Western money, audiences, and stars. But all of these films (except Max, Mon Amour) are still explorations of what being Japanese meant, and what it means.

Footnotes

1 Ruth McCormack. “Ritual and the Family and the State: A Critique of Nagisa Ōshima’s The Ceremony.” Cineaste 6: 20-26.

2 Ōshima Nagisa. “Mishima Yukio: The Road to Defeat of One Lacking in Political Sense.” Cinema, Censorship, and the State: The Writings of Nagisa Ōshima 1956-1978. 222-229.

3 Ōshima Nagisa. “Perspectives on the Japanese Film.” Cinema, Censorship, and the State: The Writings of Nagisa Ōshima 1956-1978. 7.

4 Ōshima Nagisa. “The Laws of Self-Negation.” Cinema, Censorship, and the State: The Writings of Nagisa Ōshima 1956-1978. 52.

5 Ōshima Nagisa. “Beyond Endless Self-Negation: The Attitude of the New Filmmakers.” Cinema, Censorship, and the State: The Writings of Nagisa Oshima 1956-1978. 48.

6 Ōshima Nagisa. “My Father’s Nonexistence: A Determining Factor in My Existence.” Cinema, Censorship, and the State: The Writings of Nagisa Ōshima 1956-1978. 202.

Edited by Olga Tchepikova-Treon