| Ben Jarman |

Captain America: The First Avenger plays on glorious 35mm at the Trylon Cinema from Sunday, August 24th through Tuesday, August 26th. For tickets, showtimes, and other series information, visit trylon.org.

Up until his death, Stan Lee showed up in a cameo role for every movie that’s part of the Marvel Cinematic Universe (MCU). Even general audiences loved finding him pop up as a postman or security guard. Appearances like this quickly made Stan Lee a household name, everyone mistakenly knowing him as the creator of the Marvel Universe. However, Lee only assisted with aspects of the Marvel Universe. Comics, being a visual art form, need artists to pencil stories to life. Though Lee promoted the basics of many important Marvel comics, he didn’t create them or bring them to life like the artist Jack Kirby. Even more, Lee had absolutely nothing to do with the creation of Captain America—unlike Kirby, who co-created the character with Joe Simon in the 1940s. Without the visual stories rendered by Kirby for Captain America, Joe Johnston’s film, Captain America: The First Avenger and the entire MCU would not exist.

After Jon Favereau successfully brought Iron Man to screens, Captain America was one of the next options for a big screen adaptation. Thoughtfully, the producers agreed to make the film a period piece, matching the style and setting of the original comic. Director Joe Johnston was brought in to direct, partially due to his experience handling another World War 2 superhero adaptation, The Rocketeer. In an interview with SlashFilm, Johnston states, “This period particularly is appealing to me, because visually the 30s and the 40s feels to me like it was a time when people cared more about what stuff looked like.” In addition to this, he needed an understanding of the Captain America character. In the same interview, Johnston reveals, “I read every Captain America comic that I could get and I sort of researched where he came from and where he started and the various iterations of him over the decades.” Johnston had all the right tools to assemble the film, so now it was time for action.

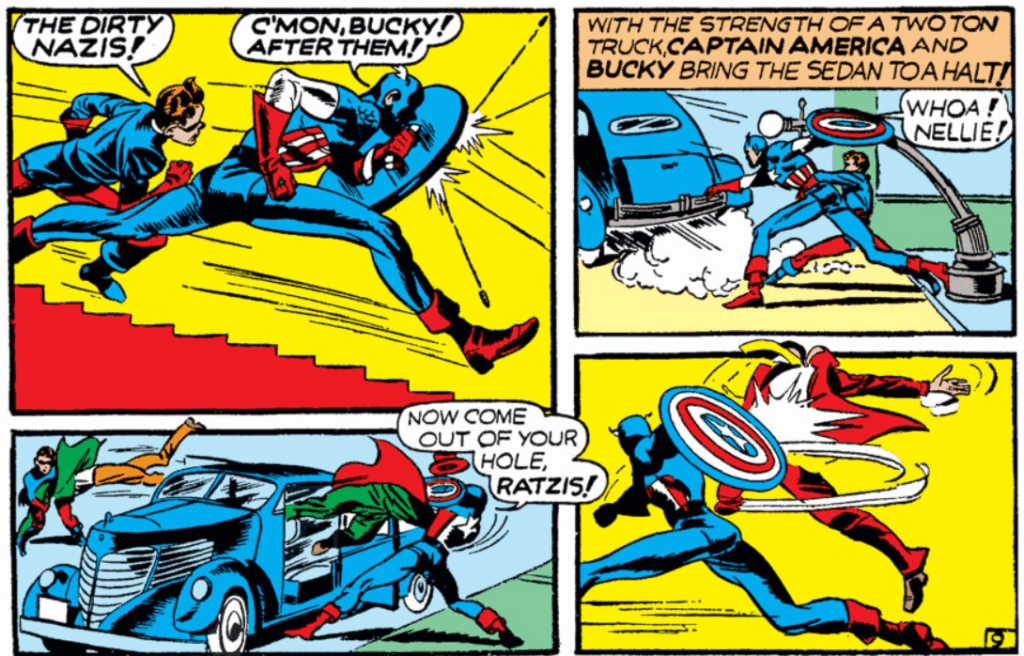

Captain America Comics 2, page 9 (1941).

Where does the action come from? Most likely from the actors and the crew working on the film, but what was the inspiration? Partners Jack Kirby and Joe Simon need to be thanked for this. In the 1940s, World War 2 was in full effect and the country needed inspiration from heroes in real life and fiction. Captain America was just the ticket. Fighting the nefarious Adolf Hitler right on the cover of the first issue, Captain America and his partner Bucky were a great force of spirited propaganda aimed to embody the qualities needed to stop the Axis Powers. Even more, Captain America was once just weakling Steve Rogers, a kid from the streets of New York unfit for combat. Unlike the cosmic invincibility carried by a rival publisher’s Superman, Rogers was just a regular guy, volunteering to take the serum that would turn him into a super soldier. This was a man no different than any man walking down the street; a man with his own problems to relate to.

How close was Jack Kirby to this “regular guy?” Pretty close! Kirby’s immigrant parents raised him in a New York City apartment.1 The streets were home, taking odd jobs to help the family and fist-fighting other kids that formed the numerous gangs in the area.2 This was the American dream; fighting, physically and mentally, for your place. Here is young Steve Rogers, growing up in the same place as Kirby, now brought to the screen. The scene in question sees a frail Rogers cornered in an alley facing the neighborhood bully. Knocked down, but never giving up, Rogers rises and says, “I can do this all day.”

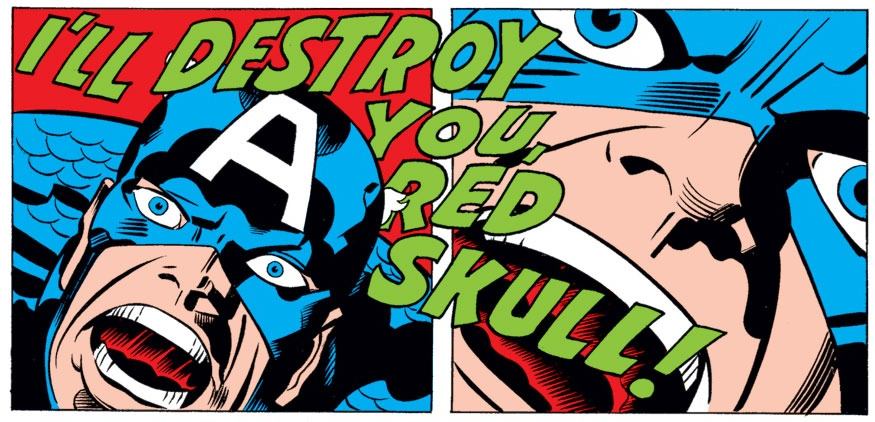

The Avengers 4, page 4 (1963).

Eventually, Kirby himself was sent to war just like the character he drew.3 The horrors he encountered were jarring compared to the war stories he told through Captain America. In a letter to his wife, Kirby writes, “I landed on another planet. The GIs remind me that war is real and that the Nazis that started this horror are not comic book characters.”4 In France, Kirby was on the frontline acting as a replacement for other ravaged troops. Pushed to his limit, Kirby was removed from the action due to frostbite and eventually made it back to the United States. His memories of the war haunted him for the rest of his career. You could certainly see it in his drawing style.

Even before the war, Jack Kirby had a drawing style he championed. His fights were big and could really convey motion and action like no other. Kirby set the standard according to MAD Magazine creator Harvey Kurtzman, who says, “His understanding of mass and movement was uncanny, filling his pictures with so much action that they bulged beyond the borders of the panels.”5 At the center of this was Kirby’s love of cinema. In The Comics Journal, Kirby says, “I was a movie person. I think it was one of the reasons I drew comics.” His drawings captured the moving pictures of cinema with still drawings. After the war, this continued, but his style evolved, creating art with exaggerated elements. His imagination often became larger than life, making it possible to quickly create worlds so engaging that audiences wanted more.

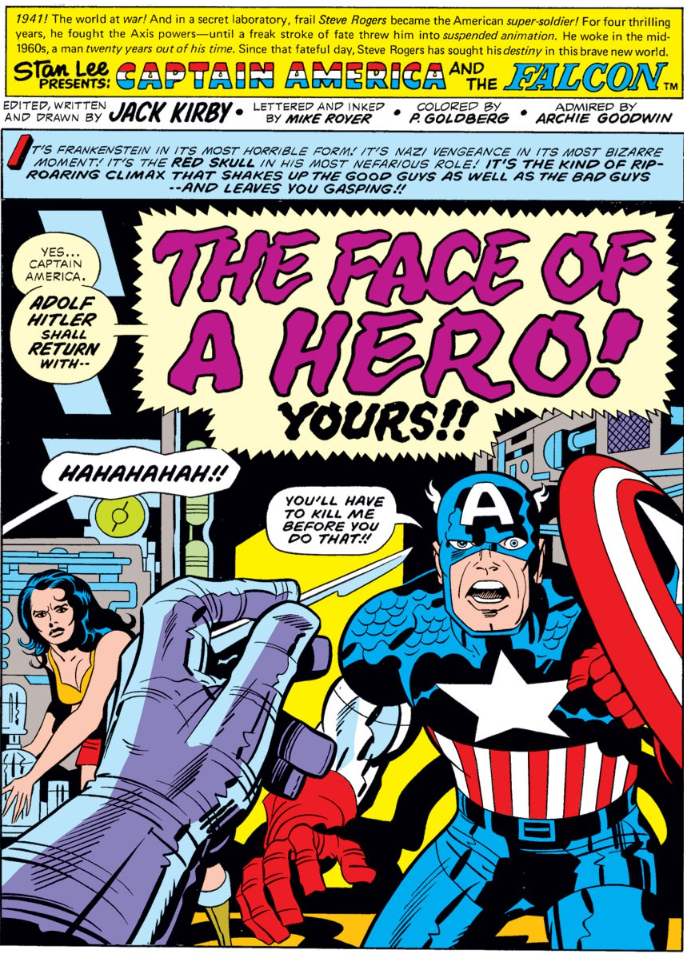

Captain America 213, page 4 (1977).

Several years after the war, Kirby was back working with the same publisher that printed Captain America. One day he entered the Marvel offices in New York City and saw the furniture being removed. Stan Lee, the young nephew of the publisher, was upset because the company was out of money. Kirby knew he had to do something because he had a family to care for, so with little hesitation, he got to work on the creation of new Marvel comics that could capture the attention of readers. In the same interview from The Comics Journal, Kirby states, “I came up with The Fantastic Four, I came up with Thor (I knew the Thor legends very well), and the Hulk, the X-Men, and The Avengers. I revived what I could and came up with what I could. I tried to blitz the stands with new stuff. The new stuff seemed to gain momentum.” He even brought Captain America back to life from the icy waters of the ocean, just as seen at the end of Johnston’s movie.

Kirby left Marvel in 1970—not because he was too old, but because he was treated unfairly by the publisher. Years of missed royalty checks and credit discrepancies soured him. It was all centered on his partnership with Stan Lee. Lee acted as someone to bounce off ideas, but ultimately, Kirby orchestrated everything else. In the background, Kirby’s ideas were also used to make cartoons, posters, and clothing without compensation or his knowledge. Kirby elaborates in The Comics Journal, “I should have told Stan to go to hell and found some other way to make a living, but I couldn’t do it. I had my family. I had an apartment. I just couldn’t give all that up.” After experiencing the same treatment with Marvel rival DC, Kirby returned to Marvel once again, taking on Captain America for a third time.

Recently, Marvel released a new version of Fantastic Four. Unlike other MCU characters he created, elements of the film were much more in line with Kirby’s vision. Galactus has the same complex mechanical details common in Kirby drawings. Yancy Street was used, which is a stand in for Kirby’s own childhood neighborhood. This focus on Kirby in the film commemorates the importance of the Fantastic Four as his creation and how it saved Marvel Comics. Large sums of money were tossed at this movie and all the films in the MCU. Captain America, Ant Man, and Iron Man are responsible for one of the most successful movie franchises ever and it came out of the head of a kid from the streets of New York City. And this isn’t so farfetched; comics are just movies that require a bit of imagination to move. In an interview with Tim Skelley, Kirby says, “I feel comics themselves are sort of a frozen movie. Each artist is producer, director, and casting director. It’s got to be written like a movie, staged like a movie, and each character acts as individual characters … at least mine do, and I feel that gives the comic strip some sort of life and some sort of motion.”

Captain America 212, page 1 (1977).

Footnotes

1 Scioli, Tom. Jack Kirby: The Epic Life of the King of Comics. Ten Speed Press, 2020. 2.

2 Scioli, 8.

3 Scioli, 53.

4 Azéma, Marc and Jean Depelley, directors. Kirby at War. Passé Simple / Metaluna Productions / France 3 Grand Est, 2017.

5 Evanier, Mark. Kirby: King of Comics. Abrams, 2017. 56.

Edited by Olga Tchepikova-Treon