| Malcolm Cooke |

The Great Escape plays at the Trylon Cinema from Sunday, August 31st, through Tuesday, September 2nd. For tickets, showtimes, and other series information, visit trylon.org.

For the past few months or so my father has been digging a very large hole in his backyard.

It started with some error in the installation of a rain garden I always struggle to comprehend the details of. The contractor said a previous hole that was filled needed to be completely redug to be 10 by 12 feet and 48 inches deep.

“I can have my guys do it.” He told my father.

“No, that’s fine, I’ll do it myself.” He responded.

The fascination with digging a hole, with or without any good reason to do so, is widespread. There are books like Louis Sachar’s well-known 1998 novel which has delinquent youths digging hundreds of holes in a desert as punishment. There are video essays and video games all about digging a big hole. #DiggingAHole on TikTok had 11.9 million views in 2022 (probably many more today).1 Some people spend decades digging vast and complex tunnels as part of the phenomenon of “Hobby Tunneling” and there is even an organization for “aimless digging” called HoleSoc.2

.

Some people have good reasons—at least ostensibly—to start digging holes, such as to dig a cellar or for an art project. But like in the case of the infamous “Moleman” of London, William Lyttle, such a project soon becomes irrelevant in the face of an ever-expanding compulsion. At the time of his death Lyttle had been digging for 40 years and the fines from damaged sinkage in the streets above his tunnels led to fines of over £350,000 for no real reason aside from him wanting to keep digging.3 For many people there seems to be something extremely compelling about the act of digging a hole for no other reason than the pure satisfaction of making it deeper.

So what does all this have to do with John Sturges’s 1963 classic war movie The Great Escape? Well, because it’s about digging a hole of course!

Sturges had encountered the memoir of the same name by Paul Brickhill in the 50s and was interested in making it into a film, but it wasn’t until his breakout success The Magnificent Seven that he had the influence to get the project made.4 The story follows a group of downed pilots from various allied air forces kept as prisoners of war. As Kommandant Von Luger (Hannes Messemer), the German Luftwaffe officer in charge of the camp, explains to RAF Group Captain Ramsey (James Donald) upon his arrival, this particular group of prisoners are those renowned for breaking out of countless other camps before being recaptured. This camp has the strongest and most sophisticated security methods employed so far in the war. In the words of Von Luger: “Give up your hopeless attempts to escape. And with intelligent cooperation we may all sit out the war as comfortably as possible.”

But of course both sides know that that won’t happen. “Colonel, do you expect officers to forget their duty?” Ramsey tells him.

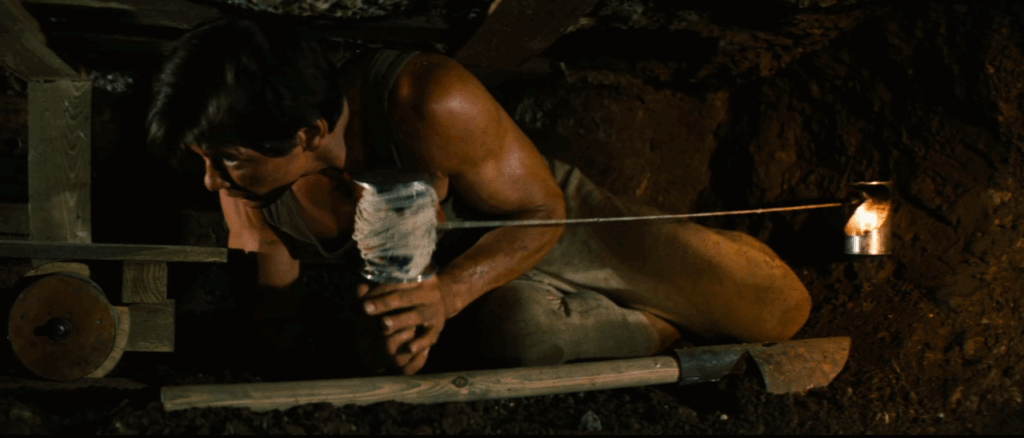

The duty to escape, of course, is where much of the fun is to be found in the film. While many of the characters and situations are fictionalized from Brickhill’s memoir, what’s left largely intact are the logistics of the construction of the three tunnels built in the film. The famous method of off-color dirt disposal through bags hidden in prisoners’ pants while gardening, the usage of wooden bed slats as tunnel supports, and choir practice to disguise the sound of hammers all actually happened.

The process of digging the holes (three tunnels, actually, nicknamed “Tom,” “Dick,” and “Harry”) is grounded in hijinks and comedy, but also the myriad human dramas of the wide cast of characters. Although Steve McQueen’s Captain Virgil Hilts is the most protagonist-y of the bunch, it’s a true ensemble cast. We see Danny Welinski’s (Charles Bronson) ironic claustrophobia despite completing 17 previous tunnels, Colin Blythe’s (Donald Pleasence) slow loss of eyesight, or the tragic sense of doom that surrounds Roger Bartlett (Richard Attenborough) as he has been informed by the SS that this will be his last chance at escape; if he is caught again he will be summarily executed. The action-adventure genre trappings are woven with the humanity and experiences of its characters and their hopes and fears.

Even the Luftwaffe, in comparison to the more stridently ideological SS and Gestapo, are portrayed as somewhat sympathetic. Von Luger has respect and pity for the POWs. A youthful soldier named Werner (Robert Graf) gives the nazi rank and file a human face, as a well-read family man whose hapless naivete is exploited by the heroes to smuggle in contraband.

But it’s not all fun and games, and the Nazis are still Nazis. Werner is the one to eventually uncover the tunnel nicknamed “Tom,” a moment of defeat which drives Scottish airman Ives over the edge of despair as he is killed in a last hopeless dash over the fence. And despite his sadness and regret, Von Luger can do nothing to stop the SS from executing 50 of the recaptured escapees, including Bartlett, near the end of the film.

Indeed, even with the excitement of the escape, of the 76 men making it to the other side, ultimately only three get away. Such a downer ending was part of what made the film such a hard pitch, as producer Samuel Goldwyn reportedly said, ‘“What the hell kind of escape is this? Nobody gets away!”’.

But the theme becomes clear with the film’s ending, as a recaptured McQueen is escorted off to the solitary confinement cell called the “cooler” and begins tossing his baseball against the wall, something he does when he’s planning an escape. He may have failed this time, but there’s always another hole to be dug.

The Great Escape is ultimately about resistance; perpetual forward motion in spite of a seemingly hopeless situation. Right before he is shot, Bartlett says, “You know Mac, all this—the tunneling, organization, Tom and Harry—kept me alive. And even though we… I’ve never been happier.” It’s tragic, but also with a tinge of hope. The idea that dogged resistance against a fascist regime until the very end can be its own source of vivacity. Even after complete failure, it was still worth it just to try.

It’s a broad theme, something people might even call clichéd or maudlin. But there’s a reason so many people are entranced by the urge to pick up a shovel and strike earth. Whether it be the thousand extant crises in the world or just your own age-old personal strife, there’s something comforting about the idea of taking control of some small part of the world in front of you, making some small kind of progress forward, one shovelful of dirt at a time.

My brother, over a decade before my dad started on his most recent hole, also had the idea to start digging in the backyard. I was probably eight or nine and he was 13 or 14 and I remember looking out the window to see him standing there in the hot sun, proud of his upturned dirt. Perhaps it’s an apocryphal family tall-tale that grows each time it’s told, but I think he got almost six feet deep. Maybe there’s something to say about digging a hole just for the sake of it. Hey, there’s a hardware store on the same block as my apartment. You can get shovels there.

It wouldn’t be too hard to find a spot and start digging.

Footnotes

1 Andrew Lloyd, “The Return of An Ancient Hobby: Digging Holes” Vice, August 18, 2022, https://www.vice.com/en/article/the-return-of-an-ancient-hobby-digging-holes/

2 Sarah Laskow, “The Pursuit of Personal Tunneling” Slate, September 9, 2015, https://slate.com/human-interest/2015/09/the-history-of-inspired-diggers-who-have-taken-to-making-their-own-tunnels-as-a-hobby.html

3 “Mole Man of Hackney leaves council in a £350,000 hole” The Standard, April 12, 2012, https://www.standard.co.uk/hp/front/mole-man-of-hackney-leaves-council-in-a-ps350-000-hole-6482034.html

4 Sheila O’Malley, “The Great Escape: Not Caught” Criterion.com, May 12, 2020, https://www.criterion.com/current/posts/6941-the-great-escape-not-caught

Edited by Olga Tchepikova-Treon

Pingback: What are We, Some Kind of Dirty Dozen? – Perisphere