| Lucille Hanson |

Constructing A House, Criterion Collection, 2009

Hausu plays on glorious 35mm film at the Trylon Cinema from Wednesday, October 29th, through Tuesday, November 4th. For tickets, showtimes, and other series information, visit trylon.org.

“How to describe Nobuhiko Obayashi’s indescribable 1977 movie House (Hausu)? As a psychedelic ghost tale? A stream-of-consciousness bedtime story? An episode of Scooby-Doo as directed by Mario Bava?”

That quote is what opens up the description on the Criterion Collection release of House, which is how I and many other people first watched House. This release, first put out in 2009, was the first time the movie had been in the US, 32 years after its initial release in Japan. One year for my birthday, I got together with my friends and screened House to much success. Before the screening, I provided a bit of context for them as to what they were about to see. The movie is pretty easy to describe, despite what all the blurbs I’ve read tend to say (but that also could be because I’ve seen this movie numerous times). Instead of providing them a synopsis of what they were about to see, I prepped them with a crash course in the making of House: the directorial debut of TV commercial director Nobuhiko Ôbayashi, who was given the chance to pitch a movie to Japanese studio giant Toho.

The story of Nobuhiko Ôbayashi’s House is one of my favorite film production stories of all time. It’s a tale of ambition, controlled chaos, and unwavering passion. All of that and more is a huge chunk of why I deeply admire House, but it’s also just a unique, bizarre haunted house story with never-ending charm. It’s an odd movie, but with more and more viewings, its oddity makes sense. If you were to describe it simply: House is a movie where a group of seven girls go visit one of their aunts, who lives in the Japanese countryside with her cat, where strange supernatural occurrences start to happen, causing the girls to disappear one by one. But that doesn’t even begin to scratch the surface of this movie’s absurdity, beauty, and creativity that makes it beloved by the majority of folks who watch it.

It’s the year 1975, and Universal Pictures just released Jaws, a blockbuster smash hit directed by the 27-year-old Steven Spielberg. Since the ’60s, movies haven’t been doing so hot financially, as televisions were the hot commodity at the time, especially in Japan. Cinema attendance has been dropping heavily due to TV, going from 1.2 billion attendees in 1960 to 0.2 billion in 1980.1 One of the big movies bringing everyone out of their houses to the theaters in the US is Jaws, a big genre-bending movie with a wide array of appeal. Toho especially takes notice of this and their solution to get people back into theaters is to take the formula of Jaws and make it themselves. Not a shark movie or creature feature, but the idea of a big budget movie made by a young up-and-coming director.

Nobuhiko Ôbayashi at this point was a commercial director, a profession that he took that was looked down upon by most of his friends and other directors in filmmaking. Aside from commercials, he had made a short film called Emotion nine years prior that he had screened around colleges, so Toho reached out to him simply asking for an idea. They weren’t looking for him to direct, despite how eagerly Ôbayashi jumped at the opportunity. Ôbayashi ended up going to his 9-year-old daughter, Chigumi, who the movie credited with making the story. He asked her for ideas on things that scared her, and she provided numerous examples extending from her real life (The Watermelon, The Clock, Sweet’s Futon Attack and the Piano were just a few of the ideas taken from her fears). Nobuhiko later explained, in an interview on the Criterion disc (where all forthcoming quotes will be taken from), “[adults] only think about things that they understand… children come up with things that can’t be explained.”2 He and screenwriter Chiho Katsura then pieced it all together, and wrote the aunt and her backstory from personal experiences with WWII and Hiroshima.

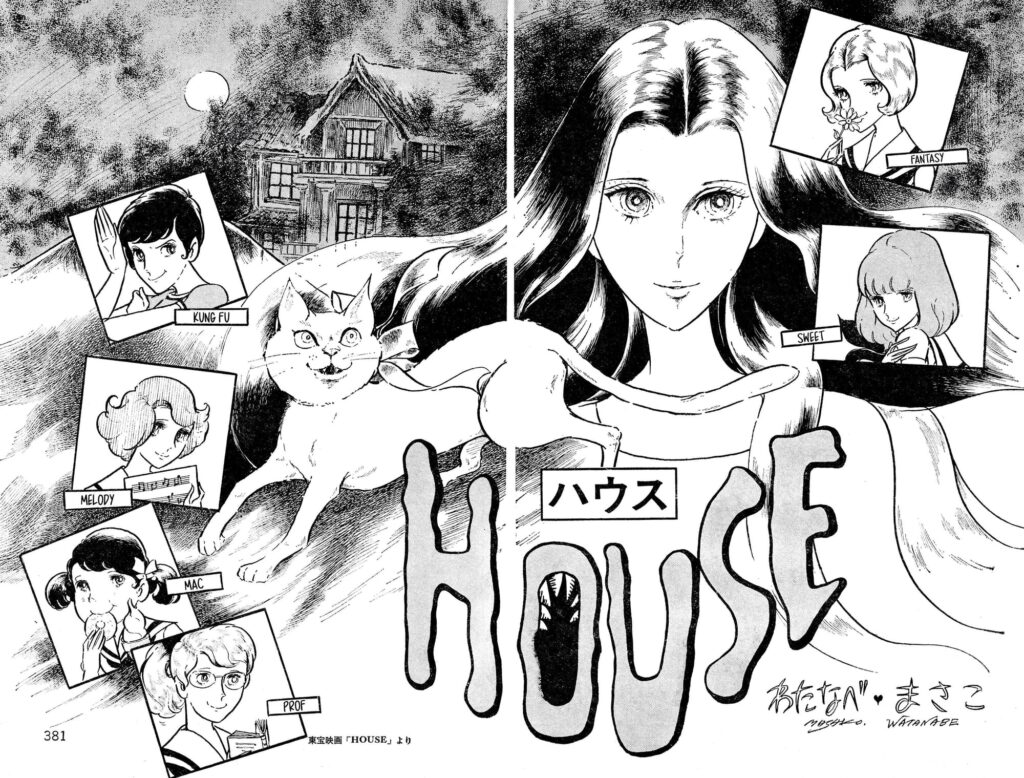

The duo fully expected the script to only be approved after months and months of heavy discussion at Toho, if not completely rejected. Three hours after submission, it was greenlit. However, no one at Toho wanted to direct it as they felt it will ruin their career. Ôbayashi jumped at the chance to offer his directing duties but was turned down by Toho because he wasn’t part of their studio system. He asked if he can tell people that Toho will be making it, to which they say yes. He then made a poster design, slapped it in business cards, and started promoting House like WILDFIRE. Before House was even in production, Ôbayashi’s promotion led to the script’s adaptation into a novel, manga, and radio drama. A soundtrack was recorded too. Two years later, in 1977, Toho gave in and told Obayashi that he can direct it.

Masako Watanabe, House, P. 10.

Given that Nobuhiko had two years of preproduction which he “used every second” in between the 200+ commercials he made during that time, he started casting the movie in his head. Besides the performers who play Gorgeous and Auntie, the main actresses are mostly models that Ôbayashi worked with in these commercials. Yoko Minamida, who plays the aunt, was the most experienced actress at the time. Nobuhiko said this role was hugely important for her because in Japanese Cinema “once an actress plays a mother, she’ll never be cast as a young girl again.”

Nobuhiko found it a bit of a challenge to use his words to direct the girls. So instead, he sat at a piano and played the theme song to House in different keys to channel the right emotions for their performances. Nobuhiko says that he always considered “making movies [as] a kind of fun,” and it’s good to know that the cast and crew felt the same way. They could not stop giggling, cracking jokes, and playing around. Making House was like he was making a movie with his friends. Storyboards weren’t made for House. Instead, Nobuhiko came up with shots on the day of shoot, which led him and cinematographer Yoshitaka Sakamoto to do all of the effects in-camera. They wanted them to look fake, like something a child could reasonably do on their own (things like pouring blue paint over someone to act as a chromakey), so they avoided asking Toho’s in-house effect team for help. They were constantly experimenting with different techniques and wouldn’t see the results until the editing bay, so no one knew how the effects would turn out. Personally, I think they turned out incredible, and led to some incredible stylistic choices that helped the movie stand out to those who end up watching it.

House finally came out in 1977 to financial success, but it was critically panned. Nobuhiko remarked that he remembered some of the reviews saying things like “this is not a film” and that House’s successful was “the death of Japanese Cinema.” In the same interview, he stated “It didn’t receive many reviews. I think reviews were often ten lines or less.” Co-Writer Chiho Katsura actually spoke to Yorihiko Yamada, one of House’s producers, who ended up saying that they “didn’t want to have a hit with this sort of movie.”

I’ve seen House countless times, and nearly every time I get something new out of it. My experience has gone from “bizarre and WTF did I just watch” to “a very goofy, charming horror comedy” to “a goofy haunted house movie that’s also an emotional fairy tale about the effects of WWII on everyone young and old.” Its initial reputation, and permanent history on the back of the Criterion cover is honestly a tragedy. Sure, for a first time viewing its mishmash of descriptions preps you well, but for subsequent viewings, its legacy being “an episode of Scooby Doo directed by Mario Bava” almost feels like a joke. House is still goofy, visually bizarre and has a lot of moments that are genuinely funny and charming, but the emotional core of the movie is the Aunt, and its post-WWII generational trauma is unavoidable when watching the movie. The Aunt is a character who is jealous of all the girls for not going through the war. To her, they have never had any pain or suffering in life, so her jealous spirit eats them so she can remain young and wait for her husband forever. There’s so much in each of the girls’ interactions that adds more meaning/motive to why the Aunt does what she does. There are numerous images and moments that made me genuinely emotional while rewatching House for this piece. It also has a guy who gets so scared that he turns into a pile of bananas. Both can coexist and do perfectly in House.

Nobuhiko ended up making 55 feature-length works in his career some more explicitly spelling out his grief from WWII (2017’s Hanagatami being the big example, which he had written long before House), but never losing that childlike whimsy in his filmmaking spirit. It’s why so many people come back to his movies time and time again. It’s why people still flock to House after all these years. It’s why Trylon runs House on Halloween every year. Regardless of what you make of them, there’s power, joy and wonder to all of his movies, especially House. And with Trylon running some more of his films after their week-long run of House, I hope that fans of House will attend these other screenings to see the joy, wonder and passion that kept fueling him for decades. I know I will.

References

1 Currents Of Japanese Cinema, Tadao Sato, P. 244.

2 Nobuhiko Obayashi, Chigumi Obayashi, Chiho Katsura, “Constructing A House”, Interview by Criterion Collection, 2009. All subsequent quotes in the text are from this interview unless otherwise noted.

Edited by Olga Tchepikova-Treon

I’ve heard on the street that the Trylon hasn’t been around for 21 years. (╭ರ_•́)

Error on my part! The Trylon description for House had “for the first or twenty first time”, so I included that as a little piece. Maybe they’ve been running it since the Oak Street Theater days, but that’s hard to check. Either way — definitely should’ve fact checked that part. My apologies!

No worries! If you’re curious, this is actually year sixteen… so almost!

I went on a second date to see this movie for the first time, around four or five years ago, and now I’m taking my best friend to see this with me next week