| Lucas Hardwick |

Night of the Juggler plays at the Trylon Cinema from Friday, November 7th, through Sunday, November 9th. For tickets, showtimes, and other series information, visit trylon.org.

***Mildly rotten apples ahead***

In the hierarchy of entertainment juggling is somewhere between miming and magic outranking puppet shows but only slightly less compelling than street buskers (depending on what the busker is playing, of course). In case you’re wondering how low the bar is, parades are dead last—they don’t even make anyone pay to go to a parade.

Juggling, like everything else in the world it seems, naturally dates back to ancient Egypt with the earliest recorded instance of the act scrawled on a panel of the 15th tomb of an unknown Egyptian prince in the Beni Hasan cemetery located between Asyut and Memphis. Given the Egyptian custom of surrounding themselves with things they loved while they were alive, it seems the mysterious prince really got a kick out of juggling, and that jugglers, like most things in found in Egyptian tombs, may have held some kind of religious relevance.

We all know someone who can juggle and its almost always the person in the room we least expect, and they’re always more than happy to show off the fruits of their learned ways, somehow conjuring three palm-sized objects ripe for tossing in the air for a few seconds before fumbling them to the ground, graciously receiving peppered applause, feigning humility and saying something like, “It’s been a while.”

The most obnoxious juggling entity, however, is the ex-boyfriend, when sometime in the early phase of new girlfriendom it’s revealed that, “my ex could juggle,” and the present non-juggling suitor is forced to smile and nod and say, “That’s cool,” in the name of decorum and maintaining any possibility of eventually getting to second base.

But despite its social ramrodding tendencies, juggling is the Taylor Swift of recreational peculiarities—exasperating, yet brimming with talent. One should look no further than the Gandini juggling troupe’s “Smashed” performance where for one hour nine jugglers juggle 100 apples in a quirky stage show that plays like the haunted dreams of a Cold War era Hungarian hobo clown set to music ranging from Bach to Tammy Wynette.

Juggling apples dates back to the 5th Century AD. The Irish warrior Cú Chulainn is said to have juggled nine apples, a shield, and a sword simultaneously. In the 1700s French acrobat and juggler L’incomprable Dupuis juggled only three apples at a time but his specialty was catching them on forks held in both hands and in his mouth. In the 1910s juggler Charles Carson became the first person to perform the “eating the apple” trick establishing his own health care plan consuming around 60,000 apples in his juggling career.

Most jugglers, however, are subscribers to the Apples Are Satan Gazette as the ol’ “eating the apple” trick has long plagued the juggling community as the most hated bit amongst jugglers. Jugglers abhor this trick not only because it’s incredibly difficult to perfect, but because audiences love it although it lacks the technical artistry jugglers pride themselves in using to suck all the air out of the room.

In a move that’s sure to go down in history as shots fired in a juggler civil war, speaker, author, entertainer, STEM advocator, Guinness World Record holder of Guinness World Records, and professional show-off David Rush dared to put the eating the apple trick to the ultimate test. Rush is the current world champion of the “most bites taken from three apples whilst juggling in one minute.” In June 2024 Rush is recorded as taking 198 bites from three apples in one minute beating his own record of 164 bites in 2016. Though it may lack any technical artistry, Rush’s single minute attempt to keep doctors away for life is something behold.

There is no one kind of apple that jugglers prefer but in the spirit of a loathed tradition within a loathed tradition, it’s safe to assume Minnesota’s own Honeycrisp apple would be the perfect apple for juggling. It’s round shape, versus the top-heavy Red Delicious or the sometimes unbalanced Fuji apple, provides a comfortable grip and evenly distributed weight fit for hands of all sizes. Honeycrisp’s larger cell structure allowing for its signature crispness and ease of rupture offer the perfect density for tossing and eating at consistent rate.

However, much in the way jugglers detest the “eating the apple” trick, apple farmers likewise disrelish the finicky-to-grow Honeycrisp.

Like a lot things we love in the world, Honeycrisp was developed pretty much by accident. Borne from a program that began in 1960 by the University of Minnesota to create a winter-hardy apple, the Honeycrisp stemmed from what was believed to be a cross between the Macoun and Honeygold apples. The seedlings from this hybrid were designated as MN 1711 and set to be discarded after being damaged during the winter of 1977.

In 1982 University of Minnesota horticulturist and Honeycrisp hero David Bedford rescued one of the original MN 1711 clones from termination at the 11th hour and decided to give it another shot. At long last, after nearly 30 years of development, a patent for Honeycrisp was secured in 1988 and the apple was finally released to the world in 1991.

Later genetic testing found that Honeycrisp is actually the child of the Keepsake apple and an unreleased variety by UMN known only as MN 1627. Further ancestral research revealed that Honeycrisp is the grandchild of Golden Delicious and Duchess of Oldenburg, an English apple brought to the US in 1835.

Eventually named the official fruit of the state of Minnesota, Honeycrisp was the first apple to ever be patented, changing the apple game going forward leading the way for other patented brands like SweeTango and Cosmic Crisp.

Though it be America’s darling apple with just the right sweet to tart ratio and perfect crisp, Honeycrisp is a real pain in the ass to grow. First of all, Honeycrisp apple flowers are self-sterile and require another apple variety in proximity to serve as a pollenizer, so farmers are looking at planting a whole different kind of apple just to get Honeycrisp. Secondly, Honeycrisp’s firmness doesn’t do well in high yields, so less is more which like everything else in the world, cuts into farmers’ bottom line, also making Honeycrisp a more costly apple for consumers. Honeycrisp is commonly prone to apple ailments like powdery mildew and black rot. Its wood is brittle requiring more support, it can crop early, and it has a thin skin making it difficult to store. And because Honeycrisp can often grow big, it is given to the calcium deficient affliction of bitter pit.

While tedious to grow, Honeycrisp’s simple virtue of being a perfectly delicious apple is akin to the honest delight found in the juggler-maligned “eating the apple” trick. Unbeknownst to the affected parties, jugglers and apple farmers are united in a single cause, in a single spirit, against the unwieldy reign of big apple.

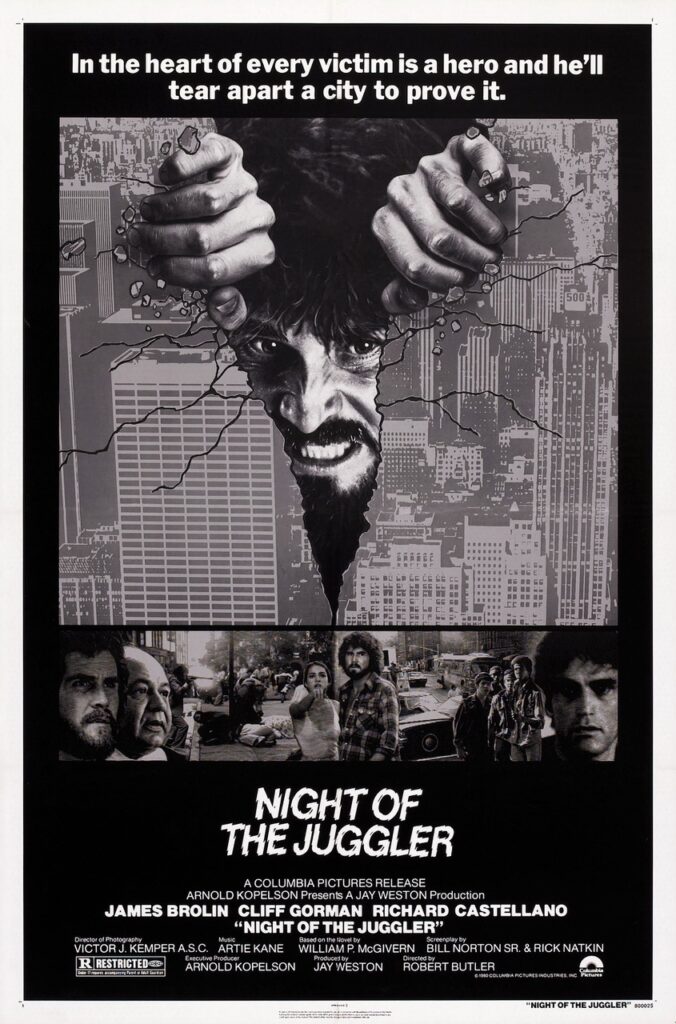

And speaking of systemically troublesome big apples, New York City is a town struggling to keep its priorities straight in Robert Butler’s 1980 sleaze adjacent, kid-for-ransom, dog-mauling thriller Night of the Juggler. Not only are there zero jugglers in the film, it takes place mostly in the daytime, making the title of the William P. McGivern book it’s based on mostly an obscure suggestion. But besides the obvious, Night of the Juggler portrays Fun City’s infrastructure as a fumbling gang of tough guys who are, least of all, eager to help.

South Bronx property owner Gus Soltic (Cliff Gorman) is fed up with the gentrification efforts by big-name land development honchos like Hampton Clayton (Marco St. John), and he’s got a real axe to grind with the city for letting the place go to hell making it easy for Clayton to buy up all the property at bargain basement prices and raze it to the ground. A justifiable argument by anyone in the landlord business, but it becomes especially dangerous coming from the noodle of a certifiable wacko with the relentless hellbent resolve of a Batman villain.

So Gus does what any certifiable wacko with relentless hellbent resolve does and kidnaps who he believes is Clayton’s daughter and dangles a million dollar ransom over the Claytons and the city’s heads lest he resort to chopping his abductee into pieces and mailing her all over town. The trouble is, in time-honored switcheroo fashion, Gus has nabbed the wrong mop-headed kid in frumpy overalls and instead finds himself on the business end of the merciless grit of truck driver, ex-cop, and dreamboat dad to the girl he’s actually kidnapped, Sean Boyd (James Brolin).

In the meantime, New York police Lieutenant Tonelli (Richard Castellano) is more concerned with his daughter’s wedding plans than he is tracking down the Travis Bickle of slumlords. While not a direct antagonist, Tonelli is almost worse given his languid approach to finding Soltic. The main authority of law enforcement in this film couldn’t be more distant from the commoner temperaments of Boyd and Soltic, strutting around in a three-piece suit complete with cufflinks, scratching his head over nuptial details. He’s planning his daughter’s wedding, and Boyd is trying to avoid planning his daughter’s funeral. If Tonelli devoted half the energy to finding Soltic as he did trying to avoid phone calls about bridal wear, this whole thing would be wrapped up in time for the ballet Sean and his daughter Kathy (Abby Bluestone) are planning to attend for her birthday.

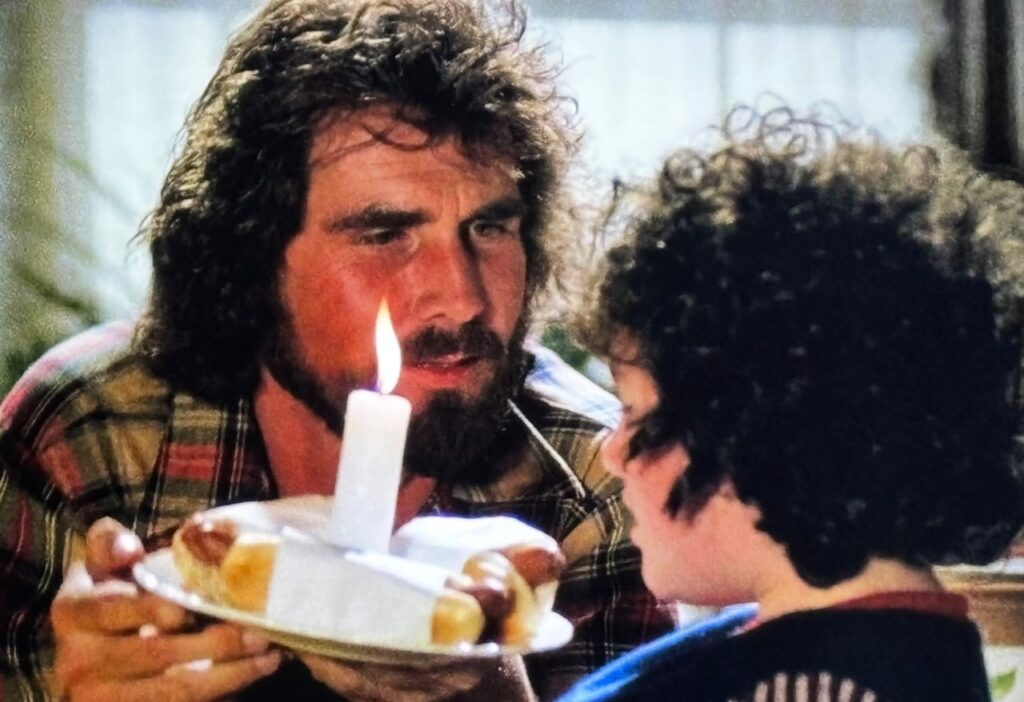

Let’s see David Rush balance hot dogs and open flame this close to bedding and frizzy hair.

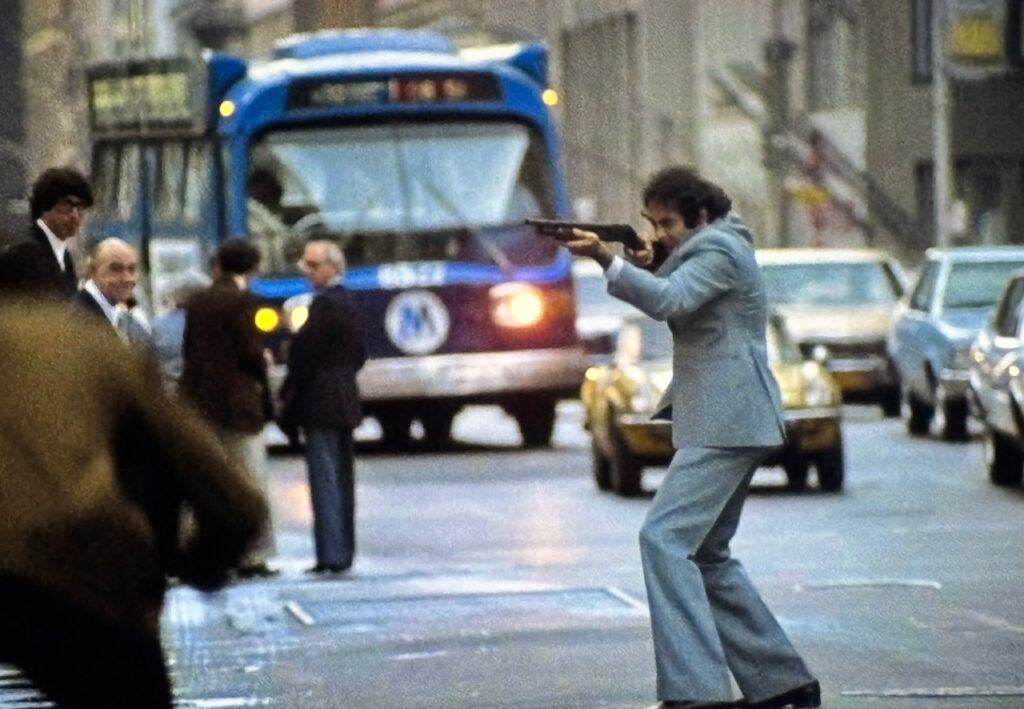

With distracted authorities more concerned about table settings and pissed off by the bacterial science behind yogurt, Boyd is left to track down Soltic on his own in a series of no less than four foot chases across a bustling Manhattan pursued by another wacko with relentless hellbent resolve, replete with you-can-see-the-whites-of-their-eyes-above-and-below-the-irises conviction, former colleague police Sergeant Barnes (Dan Hedaya). Barnes has a score to settle with Boyd for ratting him out over a little corruption involving a Puerto Rican hooker, doubling down in the ruin of his career and marriage. He doesn’t do himself any favors chucking off shotgun rounds at Boyd in the middle of a crowded Times Square, but in a city so glib about a kidnapping in broad daylight, who’s counting?

Bug-eyed, relentless, hellbent resolve.

By 1980 New York City slowly began emerging from a years long economic crisis driven by decades of increased taxes, reckless spending, and unemployment. In 1975 the city nearly defaulted on its bonds and all but went bankrupt. Unable to secure new loans to cover its spending, little choice was had but to cut budgets with big layoffs of municipal workers like firefighters and, you guessed it, police officers, setting the stage for the sloppy mismanagement and resentful discontent seen in Night of the Juggler.

After the betrayal by a city signing their paychecks, the police are apathetic to stuff like a kidnapping. And for that matter guys like Hampton Clayton are buying up all this NYC property that’s helping pay the city’s bills, so Tonelli and company ostensibly have even fewer fucks to give when they find out it was just lowly ol’ truck driver Sean Boyd’s daughter who was nabbed instead.

While The Juggler would otherwise be a terrific Silver Age comic book bad guy who robs banks and museums and somehow musters the science to open portals to other dimensions avoiding the penance of vigilante justice, the only reference to “juggling” in the film comes from Soltic during one of his nutty tirades and is a direct reference to the skeletons in NYC’s coffers suggesting the city’s history of juggling the books. It’s quite a stretch for a title, but Night of the Revenge of the Municipal Overdraft doesn’t exactly roll off the tongue. Gus Soltic isn’t wrong to be pissed off for what’s happening, but maybe he should’ve tried taking up his troubles in a city council meeting instead of breaking bad. If it weren’t for his racist rants and borderline pedophilic tendencies—“It’s time to get the gold at the end of the rainbow, sweet meat”—you’d almost feel sorry for him.

“It’s not much, but it’s home.”

Despite his connection to the police as a former cop, Boyd can’t seem to get anyone to do him any favors, especially with Barnes chasing him across the city, so he does what any dad with great hair and a plaid flannel top unbuttoned down to here would do, and conscripts the help of regular people to help him find Soltic and his daughter. While the police bumble through staging a ransom money drop and tap phone lines and plan weddings, Boyd recruits the aid of taxi drivers, dog catchers, street preachers, and 42nd Street sex workers to pick up the slack. It’s everyday people helping everyday people telling a city that can’t pay its bills that they can get by without the help. It’s the spirit of New Yorkers telling the system to go fuck itself in the best possible way with hard work, grit, and compassion for their fellow man.

In the temperament of the film’s everyman disposition, director Robert Butler, whose credits include the unaired Star Trek pilot “The Cage” and the first episode of the 1966 Batman television series, stuffs nearly every scene with objects and people in the foreground, giving the audience the sense of being casual observers in a grimy, crowded, teeming New York. The camera is often peering over shoulders and through objects to witness events like car chases and peep show rumbles and Dan Hedaya being mauled by ferocious dogs. We the viewers are as common in Juggler as the people in the film, adding credence to the movie’s intimations regarding the respectable character of good-intentioned everyday people (provided you are indeed good-intentioned everyday people).

Not unlike the similar commentary on New York in Joseph Sargent’s 1974 feature The Taking of Pelham One Two Three where a handful of thugs hold 18 people for ransom on a subway car while NYC administration hems and haws about what to do as lives hang in the balance, the city is its own worst enemy again in Night of the Juggler. A hot dog vendor at the beginning of the film tells Boyd that “10,000 people left New York last month” and adds “I can’t kill New York, but I can kill a hot dog.” The guy who runs the dog shelter laments his struggles after the city’s budget cuts. A nurse talks of a hospital closing. There are multiple references to police layoffs. Night of the Juggler not only suggests the lengths unstable people with mommy issues are willing to go when pushed to the brink by an ineffective administration, it’s also a love letter to the spirit of New York and the traditional American work ethic unfettered by the bonds of infrastructure and bureaucracy. The people doing the most good in the film aren’t connected to the city, but are instead united by the desire to help one another in the wake of an institution that presently is no help at all.

Sergeant Barnes not helping.

It’s good intentions for a universal cause that unite strangers in a failing city. No matter the occupation or ethnicity or character, everyone can get behind the fundamental plight of a parent searching for their missing child, and they’re all willing to drop what they’re doing to help as much as possible. Allessandro (Mandy Patinkin) the cabbie at the beginning of the film lets Boyd hijack his taxi. Susie (porn star Sharon Mitchell) the 42nd Street peep show girl endures a mid-peep show brawl to meet up with Boyd to track down Soltic. Maria (Julie Carmen) the dog shelter lady stays after her shift to gather info on Soltic’s dog. People helping people becomes bigger than the city’s problems that stand in everyone’s way.

The Big Apple isn’t necessarily rotten, it’s just poorly managed—lacking technical artistry, if you will. Boyd even makes a case to his ex-wife how Kathy prefers to stay in the city with him in spite of its shortcomings. Boyd’s ex-wife shouts, “You love New York!” as if it were an insult. As well, growing the perfect apple can be a fussy prospect. But the problem isn’t the apple itself, in spite of what jugglers and farmers and psychotic landlords think. Pure clean fun, perfect crispness, and the collective mettle of decent people all in it together remain the best parts and the core tenets of any good apple.

Edited by Olga Tchepikova-Treon