| John Costello |

Big Time plays in glorious 35mm at the Trylon Cinema from Friday, November 14th, through Sunday, November 16th. For tickets, showtimes, and other series information, visit trylon.org.

When a character, on stage or on screen, breaks the fourth wall and another character notices and comments, something special happens. A skilled performer involves the audience as performers in the live performance. Unlike plays and fictional films, concert films tend to be observational experiences, exciting at a remove. Onscreen audiences scream their delight, demonstrating to the viewer how to react, while the musicians perform a slightly unpolished version of the songs you’ll find on the concert film soundtrack or the performers’ existing albums. Not so, Tom Waits.

In his songs, Waits occupies multiple different characters and moods, sometimes shifting sentiment from verse to verse. Big Time (1988) amplifies Waits’s chameleonic nature. While the albums demonstrate his vocal rasping, growling, wailing, crooning, and more, the film relies on greater experimentation and captures an intensity not found in his studio recordings.

Consider the film version of the song “Shore Leave,” recorded live in concert. This song rasps free of the limited range of the earlier studio release,1 embodying the sailor character’s desperation through Waits’s onscreen physical and vocal contortions. It’s an intense performance.

Big Time features an array of musical styles, from jazz and rhumbas to laments, love poems to murder ballads, and draws on a host of influences. The film weaves together these songs through a series of what Waits calls in an interview his “personas.” Waits named only two of these personas, one in the film (“Frank”) and one in the interview (“Buddy Greco Cocktail Halloween Nightmare”), forcing me to invent a few names. The personas don’t appear in the credits.

The Lie of Normalcy

As the film opens on a title page of oversized novelties, an emcee wishes everyone a Happy New Year. A man wearing silk clothes (Tom Waits) prepares for bed, surrounded by Mondrianesque glowing cubes, an old-style ticking alarm clock, and a portable television set displaying wavy black-and-white lines. I’ll call this man The Sleeper. The Sleeper covers the TV with a shawl, obscuring but not hiding the wavy lines or muffling the static noise. He shaves with an electric razor, then pauses to consider the tool. He gestures at the television with the razor like a remote. There is an old-style click, as when television channels used to audibly change. The channels show different Tom Waits personas before returning to the wavy lines. The Sleeper dons an eye mask and goes to sleep in his Mondrianesque bed, while a different voiceover announces the band members.

The staticky TV dissolves into a stage set featuring a man wearing a white sports jacket, Buddy Greco Cocktail Halloween Nightmare, whom I’ll call Cocktail Lounge Singer. Like most of the people in the film, he’s played by Tom Waits.

Cocktail Lounge Singer tells the story, backed by lounge music, of Frank O’Brien, the main character from the song “Frank’s Wild Years.” Except this rambling version of “Frank’s Wild Years” is drawn out in a way different than the studio release of the song,2 while still capturing the basic story. Frank assumes a mortgage at 15% and settles down, marrying a former flight attendant, Beverly, who owns a Chihuahua with a skin disease. Frank sells used office furniture. He and his wife, both heavy drinkers, attempt to leave behind their wild years for an ordinary, middle-class existence. Normalcy. “They were so happy,” the song goes, before describing how Frank burns down his house and abandons his life. Frank buckles under the lie of normalcy. Beverly’s fate isn’t named.

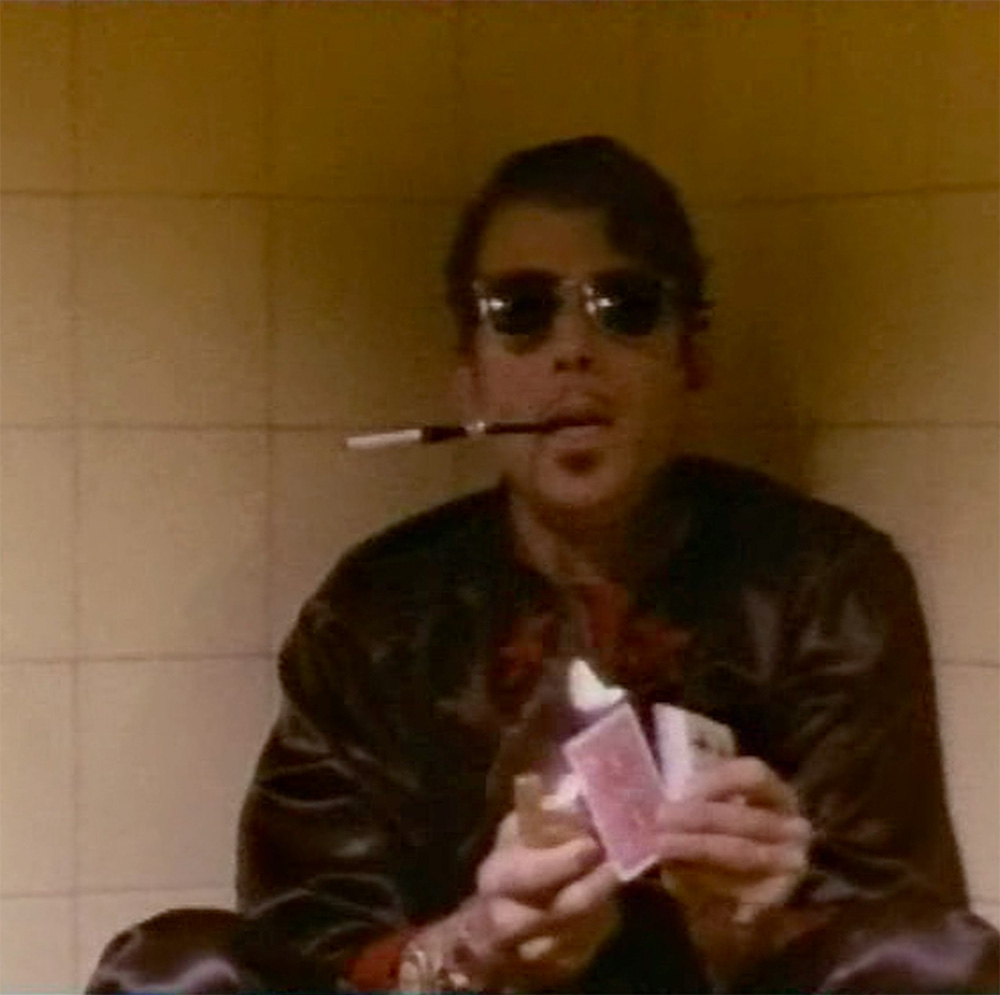

The stage set dissolves into a scene inside some kind of theater, where a man dressed like The Sleeper but wearing sunglasses indoors and carrying a work light leads an unseen person to an auditorium. In voiceover, Waits speaks in a plain, unaffected voice, declaring that Frank went to Hollywood to work in the entertainment industry, his lifelong dream. Frank (Tom Waits) now works at this theater. The closest he gets to the entertainment industry is peering through the door window into the auditorium or shining a spotlight on the performers, such as the unnamed woman (Miss Keiko), who appears in silhouette wearing a geisha hairstyle and elaborate hairpins playing a guitar while a gong sounds.3

The camera cuts to The Sleeper, who pounds on his pillow, knocking loose feathers, which fall down onto a stage where Pork Pie Hat Singer (Tom Waits) performs “Shore Leave” with a band. Throughout the film, different mechanisms will connect the different singers, performers, and personas portrayed by Waits. Throughout the film, transitions cut sharply, as when one persona reacts to another, and through the changing of static channels on The Sleeper’s TV.

The Fourth Wall of Dreams

At times, Frank addresses the camera, displaying several watches on his arm set to the time of world cities and offering to sell one to the person watching him. Cocktail Lounge Singer and Pork Pie Hat Singer address audiences that are never shown. In several scenes, the audience noises sound live, while in others I’d bet money that audience reactions were dubbed in. The only reaction shots are ones of characters responding from entirely different scenes. The sounds of the audiences may guide your reaction, but in this film, the only apparent audience is you.

The shifts in the film, combined with cartoonish dubbed sound effects, destabilize the world of documentary reality, replacing it with a differently constructed world. This is intentional. Waits’s performances mine sentiment, leaning into overwrought emotion and tenderness. Facts and details are delivered via jargon, slang, hobo speak, and hyperbole or steeped in pathos. The constructed world of this film (a construct replacing a construct), becomes not just sentimental, but visceral.

Instead of observing the film through the camera, the viewer is incited to participate in the film, provoked by the reactions, addresses, and asides among the various. Tom Waits personas, the real and dubbed audiences, the cartoonish and violent sound effects, all combine to construct meaning from the film. We are pulled, like The Sleeper, into a realm of dreams and invited to make sense of it all. It’s a worthwhile gambit.

How is this disorientation different from breaking the fourth wall in plays or avant garde concert films? Frank is an unremarkable man, a failure, a kind of everyman, while the people in Waits’s songs are similarly everywoman and everyman types, unremarkable sentimental failures all, whose lives are less notable for anything they’ve accomplished and more notable for the stories surrounding them. “You take on the dreams of the ones who have slept there,” a persona sings about Minneapolis flophouse residents in “9th & Hennepin,” all the while holding a burning umbrella. He briefly describes a woman who has tattooed tears under her eye, “one for every year he’s away,” and then snarls, “There’s nothing wrong with her that a hundred dollars won’t fix.” The song dismisses cheap sentimentality in favor of a deeper, universal pathos, the human condition, suffering combined with hope.

Other songs zoom out, encompassing communities (“The Neighborhood”) or a shared metaphysical aspiration (“Straight to the Top,” “Way Down in the Hole,” and “Clap Hands”). There’s a through line, connected by Frank and a history of people back to doughboys (a nickname for U. S. Army soldiers during World War I) forward to the “razor sadness that only gets worse with the clang and the thunder of the Southern Pacific Railroad going by” described in the song “9th & Hennepin.”

This is the reason for the contrasts between Frank, the personas, The Sleeper, Brimstone Preacher, Cocktail Lounge Singer, the women and men in the songs. The songs and the personas connect with and comment on one another, tracing aspirations toward the titular big time. In a Fresh Air interview,4 Waits equated the film’s title with the desire of a song included in the film, “Straight to the Top,” the dream of becoming a success. The personas and the song characters haven’t achieved their dreams, but they haven’t lost them, either.

If you consider the order of the songs in the film, listen to the story they tell, you’ll notice the difference between the narrative arc of the film and two related albums.5 You’d think the albums and the film would tell similar stories, but measured beginning to end, they don’t. Big Time begins with an instrumental piece, “Just Another Sucker on the Vine,” and the rambling spoken-word version of “Frank’s Wild Years.”6 You’ll have to follow the songs and dialogue weaving connections throughout the movie, until you reach the scene where Frank finally sings. And then listen past Frank’s dream-like performance to the song accompanying the credits and decide for yourself which song really ends his story.

The chance to see this rare, so-far-unavailable-on-digital movie is reason enough to venture into the cold Minneapolis night (or, in my case, fly halfway across the country). In the 1980s, the Felliniesque dream of Big Time provided a bourbon-soaked balm for the decade’s excesses, cocaine, Wall Street, and Moral Majoritizing, as well as the normalcy of mortgages, wounded dreams, and desperation. If the Trylon cinema rolled out a VCR and a projector to show the film, it would still be worth the price of admission, followed by a long gab session at an all-night diner to understand what you’d just seen. Instead, the Trylon has conjured the only 35mm print of the film, discovered last decade and on loan for only a few showings.

Footnotes

1 Tom Waits, Swordfishtrombones, Recorded August 1982. Island, 1983. CD.

2 Waits, 1983.

3 The only other character in the film besides the Waits personas and the band members, the woman also appears outside the theater and interacts directly with Frank.

4 Waits, September 28, 1988.

5 Tom Waits, Frank’s Wild Years, Recorded 1987. Island, 1987, CD.

Tom Waits, Big Time, Recorded November 5 and November 9, 1987. Island, 1988. CD. The film’s soundtrack album doesn’t include all the songs played in the film.

6 The song “Frank’s Wild Years” appears on Swordfishtrombones, the first of a loose trilogy including Rain Dogs and Frank’s Wild Years. Songs from all three films are used in this film.

Tom Waits, Rain Dogs, Recorded 1984. Island, 1985. CD.

Edited by Olga Tchepikova-Treon