| Harry Mackin |

His Motorbike, Her Island plays at the Trylon Cinema from Sunday, November 16th, through Tuesday, November 18th. For tickets, showtimes, and other series information, visit trylon.org.

Spoilers for His Motorbike, Her Island—watch the movie before you read this!

We meet several different versions of His Motorbike, Her Island‘s protagonist, Koh. First, we meet Koh the narrator. This Koh begins his narration immediately following the opening images of the film, when an appropriately old-timey font proudly proclaims “A MOVIE” over black-and-white, aggressively letterboxed frames that shutter to life. This is the reality Koh the Narrator inhabits in His Motorbike, Her Island: A MOVIE.

We hear this version of Koh’s narration throughout the film, but only inconsistently. At times, older Koh’s narration almost overwhelms the narrative unfolding on-screen. Other times, it takes a backseat for multiple scenes at a time. Koh the narrator gives us a clue for how to read these inconsistencies early on.

“Some guys have vividly colored dreams,” he tells us, “but mine were always in monochrome. This story is one of those monochrome dreams.” Koh’s narration tends to appear in black-and-white scenes, but His Motorbike, Her Island isn’t a “monochrome” movie, despite what Koh the Narrator tells us.

The very first time we see color in His Motorbike, Her Island happens as Koh waits at a red light. As he sensually caresses his beloved motorbike, color seems to ignite out of the stoplight as it changes from red to green, until it floods the frame of the memory, replacing the classic black-and-white photography with its hypersaturated parallel-opposite. If black and white is a dream or fundamental mediation, then color is aggressively unmediated; more real than real.

The Koh we watch ride his bike in color is a different Koh than the old narrator we hear or the one we watch posture in black-and-white. This Koh provides another clue for how we should read the color scenes of His Motorbike, Her Island, too: he explains his love of riding his motorbike to Mio: “Because I’m bored, I do everything my way,” he says. “I cheat my way through it all. Riding the motorbike is the only thing I couldn’t cheat my way through.”

This admission reframes the movie to that point: it does seem as if Koh is “cheating his way” through life, or at least dreaming his way through it. The Koh we’re presented with in black and white is arrogant, disaffected, bored, and—most importantly—self-conscious. We get the distinct impression that he’s the type of guy who works hard at looking like he’s not working hard. He blows off his music classes to wear a leather jacket, ride his motorbike around looking for “the wind,” and act too cool for his “boring” girlfriend Fuyumi.

Narration appears more often in black-and-white scenes. In these scenes, Koh is all performance—he eloquently soliloquizes about the wind, speaks his mind, and acts decisively. Black-and-white Mio acts the part opposite this version of Koh, too: these scenes are when she tells Koh she feels “jealous” of Koh’s relationship with his motorbike.

The Koh we see in full color isn’t nearly as confident as black-and-white Koh. Instead, he tends to come off as overwhelmed, immature, and flailing. In color scenes with Koh and Mio, Mio runs circles around Koh; he falls helplessly in love with her as she falls in love with his motorbike. This version of Mio seems as vaguely bemused by Koh’s attempts to court her as the black-and-white Koh felt about his “boring” girlfriend Fuyumi. Instead of being jealous of Koh’s freedom, he’s jealous of hers—her “Island,” and all it represents, as place and idea.

Given how His Motorbike, Her Island develops its contrast between black and white and color, it’s tempting to read the movie as two distinct stories in conflict. There’s the one Koh wants to tell and something closer to what “really” happened. His Motorbike resists this reading. Like its narration, the movie’s use of color is inconsistent. A few scenes work the way you’d expect: Koh is read for filth by his ex Fuyumi in color, and dialogue and plot-heavy sequences with Mio tend to be presented in black and white. For most of the film, however, Ôbayashi switches between black and white and color within a single scene. He does this in just about every way you can imagine, often switching from one to the other for a single shot then switching back, or fading from black and white to color for a wide transition only to snap back into black and white when the plot resumes. Reality invades the dream, and the dream invades reality—or the distinction isn’t as clear as all that in the first place.

His Motorbike, Her Island isn’t a movie about the gulf between memory and reality so much as it is a movie about how difficult (and futile) it becomes to separate one from the other—especially where love is concerned. This is the story of Koh’s coming of age as much as it is the story of his first, great love, because in the movie’s view, one heralds the other. Of course memory and desire mix and intermingle like the film’s colors. How we remember our first love is about how we want to remember that love; what we wanted to learn from it and take forward with us. What we learned about ourselves from that love. Koh isn’t the black-and-white version of himself OR the color version of himself, really—none of the characters in this movie are. Instead, they are different combinations of all of these characters, shifting at a moment’s notice, like the wind, as young people always do. Always in the process of becoming, learning who they are.

There are two crucial sequences where black and white and color share the same frame within a single scene. In both cases, it happens while the characters are riding their motorbikes. First, in one of the earliest scenes of the film, Koh rides his bike into the country while literally carrying a bloom of color with him. The color radiating from him and his bike bleeds into the landscape around him as he passes through, while the sides of the frame remain in dreamy, unfocused black and white. The dream self and the real self meet only in moments or transitions, like a long trip on a motorbike or a boat ride to Mio’s Island.

The second time this happens is in the movie’s final sequence. This time, Koh and Mio ride together, spreading their color to her island as one. The narration completes the synthesis of all the Koh’s we’ve seen to this point—past and present, ideal and real, man and feeling:

This is what I believed:

She wasn’t just a girl. That island wasn’t just an island.

She was the island. And, at that time, I became a motorbike.

She was me at that moment, and I was her.

We were the same person.

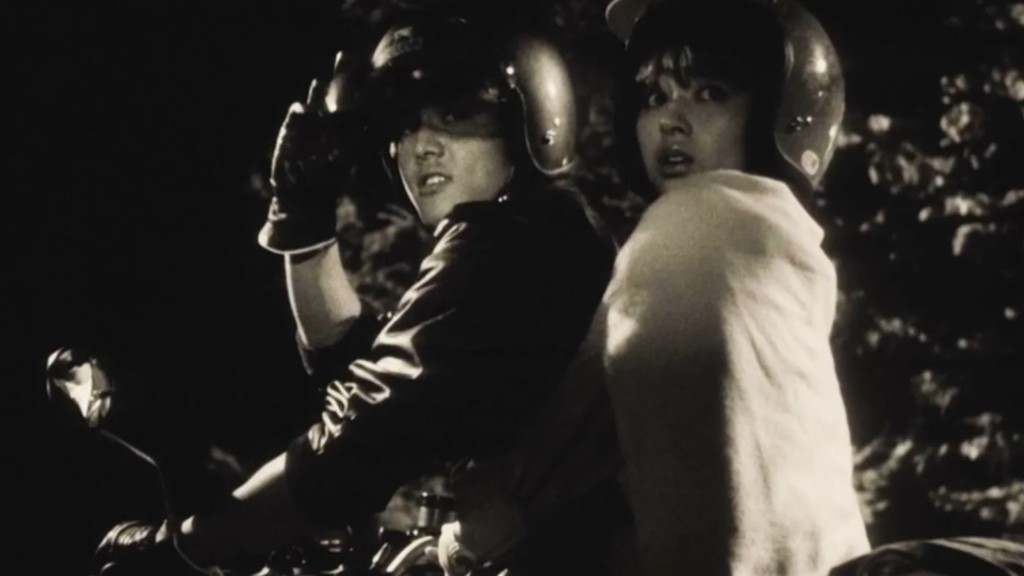

[hmhi 4.jpg here – Alt text: Ko and Fuyumi ride together. The space around them is in color, while the outer frame is in black and white.]

If the movie only ended here, the reconciliation would be complete. We’d be left with a powerful, simple, beautiful message: love is where the dream meets the reality. It allows us to become what we always wanted to be, complete at last.

But the movie doesn’t end there, because as comforting as this takeaway might be, it’s not quite true. This isn’t only Koh the narrator’s black-and-white story to tell, after all.

When Koh arrives at the diner where he and Mio agreed to meet, he overhears men talking about an accident. A woman on a motorbike swerved to avoid a rabbit in the road, hit a truck, and was killed instantly. Color images of her body invade the black-and-white scene as Koh absorbs what happened. In a daze, he wanders outside only to see her, in stunning black-and-white, saying “sorry I’m late.” The narrator completes the fantasy. “I caught her,” he says. “She was there from one summer to the next. She became my story.”

The final scene of the film takes place entirely in color, and it’s one of the rare color scenes that features narration. It’s set at an indeterminate time, in an indeterminate place—a wide, green field where the wind can blow forever. Koh and Mio prepare to pose for a photo alongside his motorbike. The narrator recalls the scene:

“What happens after we take the photo,” I’d ask.

“Don’t ask something like that,” she’d undoubtedly answer.

And then the wind would blow. It would truly be summer.

And summer is where my heart lies.

The film cuts right before the picture is taken, so we never see what happens next. The same font from the first images fills the screen: THE END.

I’ve seen His Motorbike, Her Island many times and come away with a new obsession every time. Lately, I’m obsessed with the specific wording in the final narration: “I caught her.” Even in the indeterminate future an older Koh is narrating from, he fantasizes about “catching” Mio, as if she might remain frozen in that photograph forever.

But this isn’t Koh the narrator’s story to tell—at least, not entirely. It’s also the story we watched unfold in color. Much as we’d like to “catch” love and feel it transform us into what we always want to be (a motorbike, an island), we know that can’t last. The ideal Koh felt with Mio only exists in fleeting moments; it’s made to be remembered, not inhabited. It’s a story to be told, not a life to be lived. A photograph, maybe, but never a film.

An older Koh obsessively remembers that summer from his past, “where his heart lies.” It’s the place where he learned who he was and who he wasn’t; what he wanted and what he would never have. He arrives at his own conclusion, but we see ours.

Discovering Mio was at least as invalidating to Koh as it was validating. She forces him to confront how the idea of who he is is different from who he really is. She forces him to understand that there is an unbridgeable distance between the ideal and the self. This time in his life is likely the most terrible thing that ever happened to Koh and the best, all at once. This is what it feels like to learn who we are; this is what it feels like to fall in love.

Maybe love teaches us what we aren’t as much as it teaches us what we are. Maybe we have to learn what we can never have to learn what we want to spend our lives pursuing. Maybe there will always be a difference between the stories we tell ourselves and the reality of our lives. And maybe the truth of who we want to be and how we should be lies somewhere in the space between—where black-and-white meets color.

In His Motorbike, Her Island, as in life, love is the great clarifier, where story meets life, and past meets present meets future. We become all we are in love, because we learn what it truly means to be alive—to remember and pursue and come up short and try again, again, always toward what we want to be or what we should be, even if only for a fleeting moment, a summer or a song or a motorbike ride.

Edited by Olga Tchepikova-Treon