| Ed Dykhuizen |

The Emperor’s Naked Army Marches On plays at the Trylon Cinema from Friday, January 16th, through Sunday, January 18th. For tickets, showtimes, and other series information, visit trylon.org.

Throughout the twentieth century, few documentaries managed to be both truthful and entertaining. Some were dry and deadly serious explications of important societal issues that, while enriching in the end, could feel a bit like homework. Others that provided thrills often did so by inventing scenes and passing them off as real.

The first wildly popular feature-length documentary, Nanook of the North (1922), sparked a wave of non-fiction films that showed how people lived outside of Western civilization. A peak/nadir of this trend came with the deplorable 1930 exploitation film Ingagi, which eventually became one of the most financially successful movies of the 1930s.1 Ingagi intercuts grainy 15-year-old footage of an African safari with clearly staged scenes of a topless African American woman being attacked by a man in a gorilla costume. Such racist pseudo-documentaries were delivery systems for cheap shocks, with only flimsy veneers of educational value.

During World War II, documentaries were devoted to the serious business of informing the public about the war effort. After the war, television became the primary medium for any non-fiction filmmaking, often within the domain of news broadcasts. Documentaries conformed to principles of journalistic integrity and covered topics with clear importance to society. Information was dispensed through talking heads and narration over grainy footage or photographs. Thrills and shocks were not prioritized. If you’ve seen anything by Ken Burns, you get the general idea.

By no coincidence, few genuine documentaries got significant time in American theaters in the last half of the twentieth century. Maybe if you lived in a big city, you could be lucky enough to catch a screening of a brilliant artistic achievement like The Sorrow and the Pity (1969) or Harlan County, U.S.A. (1976). Most people would only see such movies in a classroom or on PBS, if at all.

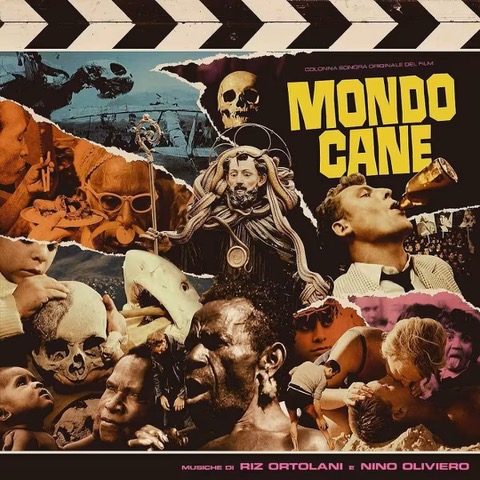

The pseudo-documentary Mondo Cane (1962) was an exception that proved the rule. It became an international box-office phenomenon by eschewing the serious journalistic integrity of its era’s non-fiction filmmaking. Mondo Cane compiles vignettes of people from around the world, some of which were staged. It is mostly an excuse to show shocking sights, such as female nudity and animal abuse, that were not allowed in fiction films in most countries at the time. Many of its scenes, especially those showing people in China, revive the racist exploitation of Ingagi.

A handful of filmmakers during this period found a way to produce documentaries that both are truthful and contain dynamic moments. Frederick Wiseman captured such shocking practices in a Massachusetts insane asylum that state authorities ensured the resulting film, Titicut Follies (1967), was banned from public exhibition for decades. With Gimme Shelter (1970), David and Albert Maysles set out to record the Altamont Free Concert and inadvertently caught a homicide on film.

Wiseman and the Maysles brothers were proponents of “direct cinema,” in which filmmakers captured real events using the then-new technology of handheld cameras with built-in synchronized sound. The footage is then assembled matter-of-factly and without any stylistic flourishes, with the goal of presenting events as objectively as possible. The finished films have no talking heads, no narration, and no musical score — just what happened.

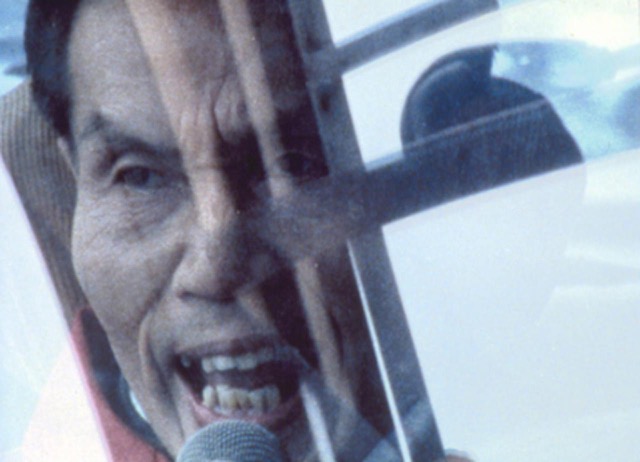

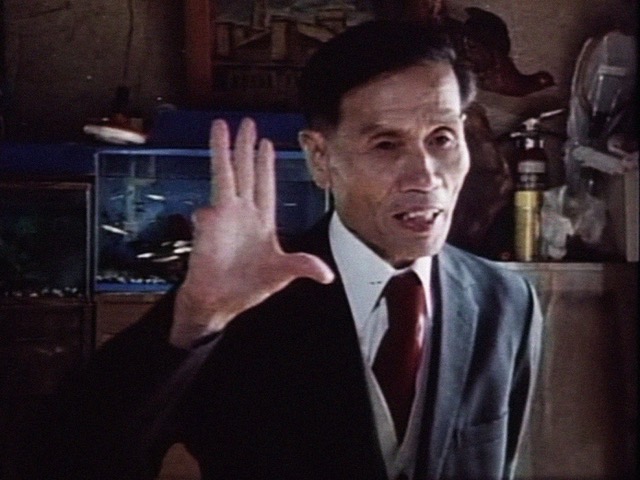

The Japanese documentary The Emperor’s Naked Army Marches On (1987) fits within this tradition. Director Kazuo Hara follows World War II veteran Kenzō Okuzaki in his fervid quest to uncover the truth about some of the war’s most disturbing events. The film consists almost entirely of Okuzaki’s various confrontations with fellow veterans and police officers. Very occasionally, silent intertitles and newspaper clippings provide important information that could not be captured on film.

Its direct-cinema style enables The Emperor’s Naked Army Marches On to present a convincing exposé of war atrocities. We are not told what to believe by talking heads or a narrator speaking over carefully edited and scored footage. Instead, we watch Kenzō Okuzaki ambush real perpetrators and force confessions out of them.

Granted, Okuzaki’s tactics could cause people to question the reliability of some of the testimonies. Okuzaki enters each interrogation knowing exactly what he wants to hear, and does not let up until he hears it. If stymied for long enough, he can do some shocking things. Viewers know from the start what Okuzaki is capable of; early intertitles tell us about his past crimes. It can still feel quite alarming to witness him erupt.

If you only read the details of Okauzaki’s life, you would likely imagine a madman driven into a messianic crusade by severe wartime trauma. The Emperor’s Naked Army Marches On reveals that that is indeed central to Okuzaki’s character. At times, however, he exhibits the politeness and deference more typical of traditional Japanese society. At times he switches from brutal hostility to humble apologies on a dime.

In one of the few non-confrontational scenes of The Emperor’s Naked Army Marches On, Okuzaki makes a touching connection with the mother of a comrade who died in the war. Our sympathies with him are pulled back and forth, creating one of the film’s main tensions. Watching Okuzaki’s behavior for two hours makes for a fascinating character study, to the point where any educational value of The Emperor’s Naked Army Marches On can seem secondary.

While Okuzaki may be single-minded to the point of insanity, his mind is driven by what almost any viewer would agree is a worthwhile goal, that of exposing the true horrors of World War II. Okuzaki often justifies his actions by saying that the revelations he uncovers are so disturbing that their widespread dissemination could prevent future wars. When one especially shocking practice comes to light and becomes central to subsequent conversations, it’s hard not to see his point.

The Emperor’s Naked Army Marches On is often a shocking documentary, but it’s not a “shock doc.” It is not a cynical compilation of alarming scenes, like Mondo Cane. The Emperor’s Naked Army Marches On has a sincere and important message about wartime atrocities and the effect they can have on a person’s psyche. And its most visceral moments arise organically, as its story and character study unfold. The direct-cinema style, in which footage is presented without any apparent artifice, makes it difficult to interpret its most arresting moments as cheap thrills. This can make them more deeply affecting, in my view.

At the risk of blatant self-promotion, I’ll mention that my book, “A History of Shock Film” (under the nom de plume Eddie Daniels), goes into more detail about how what constitutes movie shocks has changed over film history. In 1962, Mondo Cane’s gratuitous shots of topless women were major taboo-busters for most filmgoers. By 1987, when The Emperor’s Naked Army Marches On was released, female nudity in film was so commonplace that up-and-coming actresses had little choice but to disrobe on camera. To shock an audience in 1987, you had to be more artful. The Emperor’s Naked Army Marches On demonstrates one way to deliver shocks: Follow around an unstable criminal and see what happens.

The twenty-first century has proven to be a golden age for documentaries. The Jinx, Making a Murderer, and Tiger King, to name a few, have become major mainstream phenomena. They might not adhere to direct-cinema style, but they do follow the example of The Emperor’s Naked Army Marches On in recording the lives of bizarre criminals. These documentaries are not exploitative collages of shocking content like Mondo Cane (though Tiger King arguably comes close), but they are also not dry explications of serious public issues. They entertain mass audiences with outlandish real-life stories and may, in the process, reveal some deeper human truths. I would recommend The Emperor’s Naked Army Marches On to any fan of documentaries of any stripe. If you are accustomed to flashier films, its stripped-down direct-cinema style could seem dull at first. I’d encourage you to stick with it and try to adjust. By the end, you may be left more gobsmacked than you could have imagined.

Footnotes

1 Eric Schaefer’s authoritative text on exploitation films from 1919-1959, Bold! Shocking! Daring! True!, cites an estimate that Ingagi earned $4 million in box office returns (267). This would put Ingagi among the top 20 highest-grossing films of the 1930s.

Edited by Olga Tchepikova-Treon