| Lars Johnson |

Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind plays at the Trylon Cinema in glorious 35mm from Friday, January 30th, through Sunday, February 1st. For tickets, showtimes, and other series information, visit trylon.org.

In the early 1980s, an idealistic Japanese animator entered into an agreement with a magazine to create a manga on the condition that it would not be turned into a feature film. The series immediately took off and became popular. The publisher, presumably caught up in the capitalistic quest for infinite growth and more money, begged its creator to adapt it. It was agreed that a film would be made with a new caveat: the director would retain complete creative control over the project. It was greenlit and a team of a few dozen illustrators went to work crafting an unforgettable experience.

The films of Hayao Miyazaki have since become renowned in Japan and around the world. Perhaps his most visionary and daunting work is the behemoth that is Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind. First released in 1984, it stands as the definitive ecofable and a staple of sci-cli-fi, or science fiction that features man made climate change. It directly led to the founding of Studio Ghibli, whose impact goes without question and can be seen everywhere, especially at your local Barnes and Noble. Produced by Topcraft, Nausicaä is technically not in the Ghibli oeuvre but retains a place in all home media collections and box sets no less. This marks the first collaboration with Joe Hisaishi, with an utterly mind blowing soundtrack that somehow blends romantic orchestra with Daft Punk-esque synthesizers. Not only is it a perfect distillation of the Shinto worldview, encompassing deities and divine spirits found in nature, but it also is one of my favorite films of all time. Something about it feels completely fresh each viewing, like a book that may gather lots of dust on your shelf but is just as good as you remembered it being when you pick it up. It may be a bit more heady and esoteric than some of Miyazaki’s other entries, but it is quite rewarding if you stick with it. The ecological themes and unique visual palette set the stage for Denis Villeneuve’s Dune and its insect-like aircraft. The biomechanical designs of the God Warriors paved the way for Neon Genesis Evangelion. The dazzling artistry and world building on display is second to none.

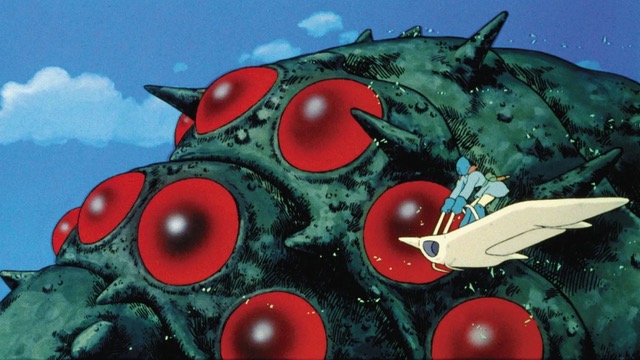

Unfortunately, the world in Nausicaä is one of post-apocalyptic ruins. The film opens showing that one thousand years have passed since a devastating war has destroyed civilization, which has created a jungle that is toxic to humans. The Ohmu, who are basically giant psychic bug gods that look like something James Cameron would dream up on ketamine, are the inhabitants. They are the guardian spirits of the forest. Their eyes glow blue when calm and turn red only when enraged. When provoked, they enter a destructive frenzy. However, this rage also scatters the seeds of the jungle, making the destruction a necessary part of the cycle of renewal. Despite looking scary, they are integral to the ecosystem, which is actually a massive bio-filtration system that absorbs the pollution and cleanses the planet. The creatures are merely reacting to humanity’s destructiveness and healing what we ruined in our hubris and thoughtlessness.

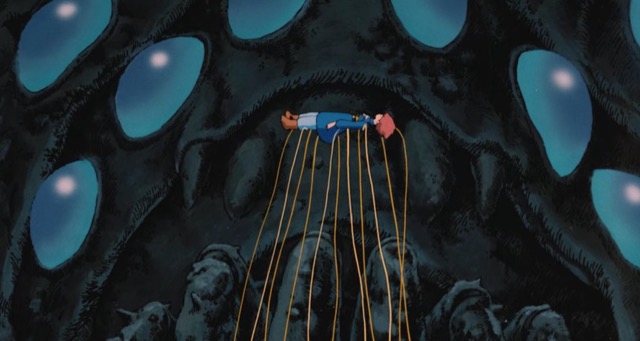

Nausicaä is the ultimate symbol of this purity. She has a special connection to the bug creatures and is able to communicate with them. Simply put, she is the messiah who restores the bond of nature and humans. She is selfless, unlike the other militaristic human characters lusting for conquest. By recognizing the environment as something that is spiritually alive, she counters the destructive mindset of industrialized humanity with radical peace and empathy. In Shintoism, it’s necessary to understand that restoring the balance means removing impurity and realigning with nature. Various rituals, like full body water immersion, are practiced that wash away your spiritual residue. Nausicaä seeks to live in harmony with the forest, embodying the Shinto ideal of purity through understanding. She believes in the inherent value of all life. Even in the very first scene we watch as Nausicaä soars through the wind on her glider, establishing her free spirit and agency.

In the second act, things take a dark turn. Nausicaä is tested when she encounters the aforementioned humans who believe that they have a divine right to destroy nature. A large airship suddenly crashes into the agrarian valley. The villagers discover unique cargo—a gigantic embryo. An armada of airships and tanks arrives shortly thereafter and storms the valley. These are the Tolmekians, and they seek to destroy the forest by reviving the embryo, an atomic bomb era metaphor called a Giant Warrior. This is repeating the mistakes of the past which led to the earth becoming a toxic wasteland in the first place. This impurity and failure to learn from the past only begets more conflict and violence. A short battle ensues and Nausicaä’s bedridden father, King Jhil, is killed. This is significant because he represents the old world and the idea that humans and insects must be separate. Nausicaä seeks unity where her father sought division and thus forges a new path for the future, free from the dogma of a bygone age. She is now ready to fulfill the role destiny has prescribed to her.

And this is where divine prophecy comes into play. A prophecy proclaims that a savior dressed in blue will come and restore humanity’s connection to nature. Nausicaä fulfills the prophecy by guiding humanity down a path of harmony and non-violence. Miyazaki wishes to destroy soulless industrialized civilization and return to a simpler age which is known in Shinto as Kami no Yo, meaning the age of the gods. This was an era predating even the first Emperor, when mankind was pure and spirits peacefully dwelled in the mountains. It’s obvious that Miyazaki thinks technology and the modern world have created a sort of disharmony; a willful severing of our connection to the divine. This friction is not just external; it’s a spiritual issue that plagues our essence. He’s gone as far to say that artificial intelligence is an insult to life itself. The message is clear; rampant greed and selfishness has poisoned our very souls. The colorless world of despair may seem without hope but the sacred remains accessible to us as long as we unflinchingly choose life and scientific curiosity.

It’s also important to remember that Shintoism is pantheistic and encompasses a near infinite amount of different beings and deities. These are called Kami. They are spirits that can be found anywhere in nature. They could be mountains, wind, trees, even rocks. They can be found in things both living and inert. It could also be ancestors from the distant past who achieved greatness. What I love so much about Miyazaki’s films is that he emphasizes these spirits can be found in mundane everyday things. He also emphasizes that these spirits can be benevolent. Think My Neighbor Totoro. Or they can be fearsome, like the demon boar in Princess Mononoke. Or they can simply be mysterious, like No-Face from Spirited Away. They oscillate between good and evil depending on your perception of them. Miyazaki’s films inspire us to see the divine as not something that is unreachable but as something present in our day to day lives, regardless of whether we can see it or not. Most of all, they teach us that we are an active and intrinsic part of the world, not separate from it.

Miyazaki’s films are uniquely timeless artifacts. However, it’s hard not to think of the modern world and all its inequities and miseries when watching this. Few films feel more relevant or urgent. Whether it’s ongoing environmental collapse, imperialist militarism, or innovation that threatens to cut us off from the natural world and ourselves, Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind feels unsurprisingly prescient. The film posits that harmony with nature is the only path to survival. We must end our reliance on powerful super weapons and emerging technology that robs us of our humanity. Nausicaä embodies the hope within us all that there is a different way—that we can understand all life is connected and have the wisdom to move beyond a destructive past.

Edited by Olga Tchepikova-Treon