| MH Rowe |

American Gigolo plays at the Trylon Cinema from Sunday, February 8th, through Tuesday, February 10th. For tickets, showtimes, and other series information, visit trylon.org.

The most interesting films tend to be those that go all the way into a gnarly little dreamworld. Not that the dreamworld of American Gigolo seems gnarly at first. The story begins by reveling in the easy brilliance of California sunshine. There’s no glare. No one sweats. A breeze is always caressing the images, playing across all those nouveau-riche accoutrements: the boxy, modernist seaside houses that are overwhelmingly windowed, the thin ties and Armani clothes, the handsome but not aggressively sporty car, the tasteful antiques. The indoor spaces haven’t been air-conditioned all to hell. Sometimes the door just stands open, and you walk right in. Noir shadows creep in later, when the film’s suspense begins to slide toward a violent dénouement that is, I think, more than a little silly. That doesn’t really matter. Then there’s the strangely beatific ending.

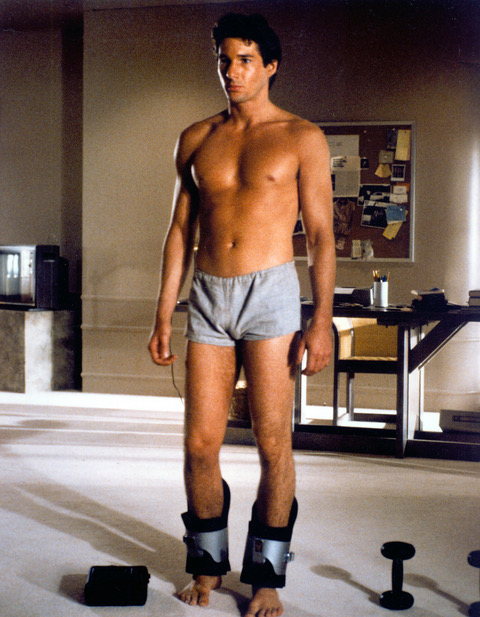

Paul Schrader, assuming he gained some control over the weather, calibrated American Gigolo for temperate pleasure. It’s the same with Richard Gere’s male prostitute, Julian Kaye, whose name sounds straight out of Kafka and is at the same time almost J.C. for Jesus Christ (or jk for just kidding). He’s a man who gives his body to the world, to women, to give them pleasure while taking little of his own, aside from a certain professional pride in a job orgasmically well done. The implication of the film is that he may be coming, but he closes himself off from ecstasy. The experience is for them, not him. He’s a connoisseur of furniture, a speaker of many languages, a man of targeted muscle-group workouts. He’s a dildo that went to college. (Actually, he’s strikingly free of any background information; when asked where he grew up, he says he came from the bed he’s lying in at that moment, like a sex toy.) We gather as well that Julian has turned tricks with men, though he’s trying, somewhat furiously, to get away from all that. The ending of the film, pickpocketed from Robert Bresson’s Pickpocket, in fact represents Julian’s farewell to both paying customers and gay life, his embrace of heterosexual devotion.

But turn the film around and look at American Gigolo as if it belonged entirely to Gere’s co-star, Lauren Hutton. Where Gere makes the film pensive and playful, Hutton makes it loose and cute. She miraculously or even incongruously adds its urgent sense of love. In Hutton’s Michelle Stratton, Schrader offers the image of a political wife married to an ascendant liberal politician in Southern California. In reality she aches to be free of a simulation.

As Michelle tells Julian, her husband wants to have a family for the sake of his political fortunes. He wants Hutton pregnant. A photogenic brood is sure to follow. What’s another manufactured Camelot? Hesitating at the factory door, Hutton chooses instead the lissome suavity of Gere and his promise of “fucking.” At first this means a different but far more satisfying simulation than her marriage. Sex with a skillful and attentive male prostitute is a far cry from family planning. It means climax with no other motive: beautiful, gratuitous, free of shame. Liberality rather than liberalism.

It’s a simulation, too, of course. Hutton knows in advance and even later that Gere is acting, or partly acting. He performs for her, even on her, as he does with the women who pay for his companionship. That’s exactly what Hutton had asked for when they met. She wanted to pay for the real thing that the “real thing” has withheld from her. Instead of a fundraising marriage, she wants to transact her desires and get what she needs, to be touched and not maneuvered.

This is what the slight but famous gap between Hutton’s teeth, more beauty mark than quirk, really means. The gap is a place where the sure defenses of appearance are down. They are a touch of nakedness. Gere may be just kidding, in some essential way, but Hutton is serious. That’s why she asks him, “How do you get pleasure?” She suspects he doesn’t, not really.

And once Hutton gets the “fuck” she wanted with him or from him, she tells Gere that it wasn’t what she expected at all. It’s “like really making love,” she says. The simulated version of the real thing has the real thing stuck in it, down there at the core, like a fly trapped in amber. She feels a sure and tantalizing bond with Gere, the greatest secret. More than anything else, she wants to bring it out into the open. That’s the love she bears for this charming and materialistic gigolo. She can tell he’s faking it, too; she tells him she knows. Sex should be about him as much as her. After all they’re doing it together.

Whimsical and earnest, Hutton’s Michelle recalls no one so much as her contemporary Diane Keaton in Annie Hall. Annie and Michelle are women who pursue what they want while caught in a trap of semi-virtual reality. Where Annie needs to get high to be turned on with her neurotic boyfriend, Michelle has an even more complex snare she senses all around her. The liberation is the trap is the freedom. She wants to make her way through the couture to reach the center of the maze where Richard Gere really is, naked at last, not merely a toy. Think only of the entirely un-vulgar way she says “fuck” throughout the film. Something holy is there. No one but Gere gives it to her.

And like Woody Allen in Annie Hall, which originally was going to be called Anhedonia (the inability to experience pleasure), Julian Kaye resists that holy joy, with women and, it is implied, with men, too. He doubts his ecstasy. He balks at pleasure with a woman who loves him so much she frees from a murder charge with a concocted alibi, unprompted. That’s how much more than sex there is to sex. There’s coming together at last, in all senses. There’s liberation, there’s something holy. There’s the gap in your teeth.

Edited by Olga Tchepikova-Treon