| Wil McMillen |

When the Wind Blows plays at the Trylon Cinema from Friday, February 20th, through Sunday, February 22nd. For tickets, showtimes, and other series information, visit trylon.org.

Everyone is scared. Everyone is broke. Unemployment is skyrocketing. There’s a madman in the White House who is threatening to blow up anyone who looks at him wrong.

It’s 1983, and I’m eight years old.

Nostalgia for the 1980s is amusing to me. The 80s, at least the early 80s, were a time of sky-high inflation (14% inflation for three years, can you even imagine?), Middle East tensions, a strange new disease with a tiny name, and a nuclear arms race between the US and the Soviets that led the nightly news.

My childhood bedroom was just outside our family’s living room. My bedtime was 9:00, but I’ve never slept well. I would lay in bed each night, listening to the shows my parents would watch in the living room, ending with the local news, and then Johnny Carson’s monologue. I learned so much about the world, laying there at night listening to the TV. It was more than I really wanted to know, to tell the truth.

I grew up in Wichita, Kansas. My friends on the playground had already let me know that we’d be blown up first in a nuclear war because Wichita was one of the places nuclear missiles would launch from. We were a sitting target. Sometimes the playground rumors are lies, half-truths, or exaggerations. This was one of the times the playground got the facts right. Until 1986, McConnell Air Force Base, in the southeast part of town, housed nine Titan II nuclear missiles. If you’re a naturally anxious kid, hearing these things only once will burn themselves into your brain.

We came so close to nuclear war so many times that autumn of 1983. It was the hottest the Cold War had been since the Cuban Missile Crisis.

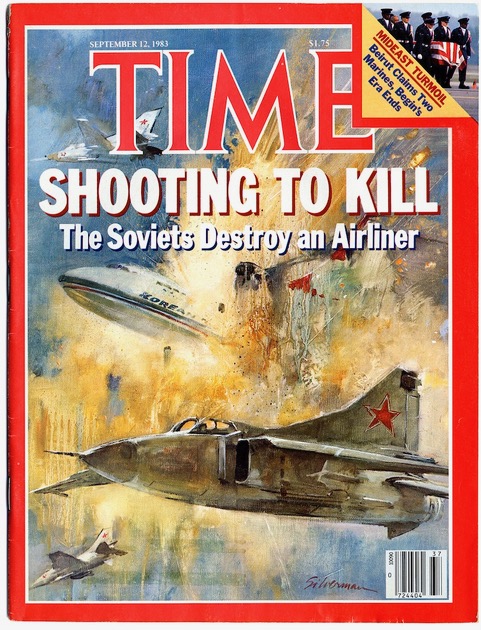

First was the downing of Korean Airlines flight 007 on the morning of September 1st. The official story is that the pilots failed to turn on the autopilot from “heading” mode to “Internal Navigation System” thus sending it over 180km into Soviet territory. The Soviets claimed it was a mistake, that they had thought it was a spy plane and even sent two warning shots to divert it. Their third shot brought it down. 246 passengers and 23 crew abord were killed, including a US Representative from Georgia, Lawrence McDonald. Soviet hardliners suspected it was a US test to see how prepared the Soviets were for an attack. President Reagan called it the “Korean Airline massacre” and “a crime against humanity.” Talks between the US and Soviets ceased. That hadn’t even happened during the Cuban Missile Crisis.

Two days later, on September 3rd, a US Navy aircraft was hovering near the KAL crash site when the Soviets determined it was a threat and launched MiG aircraft to shoot it down. The US in response launched their own warplanes to counter attack. At the last minute, the US Navy craft drifted back into neutral waters and both sides called off the attack. Gen. Charles L. Donnelly, commander of US forces in Japan, was quoted as saying “I don’t think I’ll start World War III this afternoon.”

Then, on September 27th, the Soviet early warning system, Oko, mistakenly identified sunlight on high altitude clouds as a US missile launch and went into alert. Soviet Lt. Col. Stanislav Petrov wasn’t even supposed to be on duty that night. He was filling in for another commander who had fallen ill. As the sirens went off and the computer told him that the alert’s reliability was at its highest level, Petrov could have set off World War III with one call to his superiors. “All I had to do was reach for the phone; to raise the direct line to our top commanders—but I couldn’t move. I felt like I was sitting on a hot frying pan.” Petrov was an IT specialist, and because he knew more about the system than other commanders, he suspected that a US nuclear attack would have been “all out” and not just five missiles. In a moment where it can literally be said that one person saved the world, Petrov decided to wait until corroboration came in from other sources. That corroboration never arrived and nuclear war never happened.

Into all of this tension and escalation came three films which showed in agonizing detail what we would face in the reality of a nuclear war. The biggest one was The Day After, a TV movie that aired on November 20th, 1983. It was watched by a now astonishing 100 million people, including Ronald Reagan, who was so bothered by what it showed, he changed his opinion on nuclear proliferation and eventually worked with Soviet Premier Mikhail Gorbachev to signing the Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces Treaty, a reduction in both nuclear weapons and tensions between the countries.

The second film of the three is Threads, a film shown on the BBC September 24, 1984. If The Day After is the overall view of what would happen to a city during a nuclear attack, Threads is the gritty, grimy, horror show at street level. I’m still surprised this ever aired on television but I guess the British are made of sterner stuff. The Day After ends with a black screen and the morse code signal for “Mutually Assured Destruction” playing out over credits. Threads ends with a stillborn and mutated baby born in a dirty cubical. It’s one of three or four films I’ve sworn I’ll never sit through again. I recommend it, but with reservations.

Which brings us to the third film of the trilogy, When the Wind Blows. Lesser known than the other two, this film is distinct in two ways. First, it’s animated, and second it focuses on only two characters throughout its runtime. This consolidation of characters in its own hypnotic way, makes it even more grim. The film is based on a graphic novel by Raymond Briggs and directed by Jimmy Murakami. The two previously worked together on a film version of Raymond’s most famous book, The Snowman, which also ends, in its own way, in the bleakest possible way and then cuts to credits.

Jim and Hilda live in a house in the countryside in an unnamed year, shortly in the future. The timeline is shady because the two of them are clearly in their sixties, but remember their childhoods spent during the blitz, which means the film actually takes place in the late nineties. It’s this segment I want to focus on because it explains so much of what we see. Growing up during the Blitz, the memories they have are idyllic and peaceful, almost as if it was an adventure.

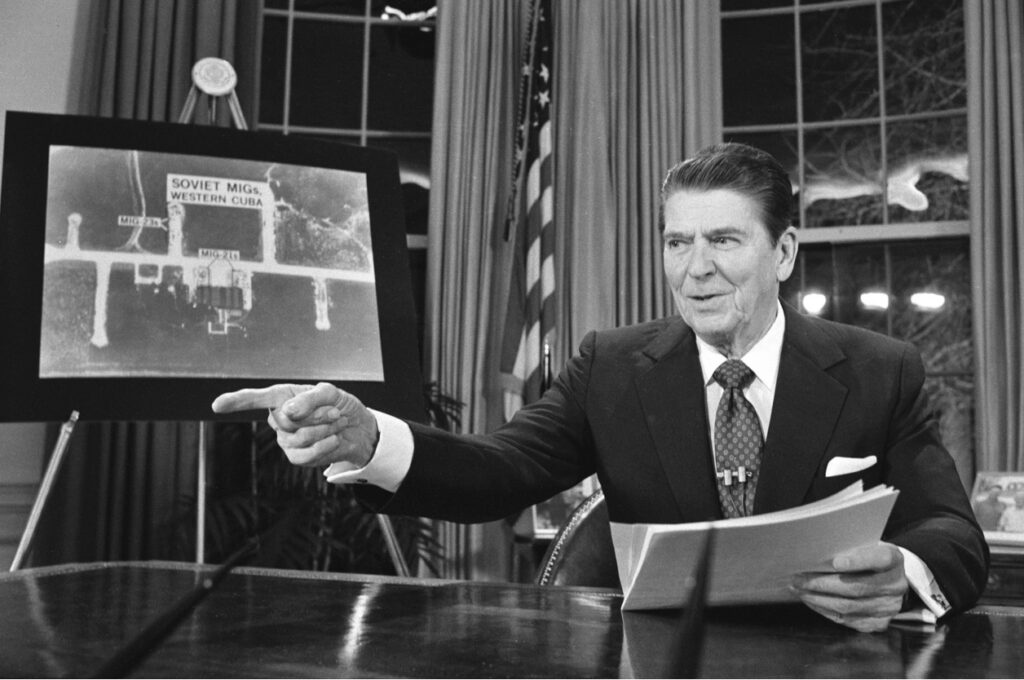

Photo 2

If they can lie to themselves about that, I suppose it makes sense that Jim and Hilda think if they follow the outlandishly insufficient advice the government has given them, then this will be an adventure much like that. Jim cheerily works around the house, getting the windows painted with white paint to reflect the radiation blast of the bomb. The government pamphlet he focuses on in the days before the bomb drops also have him create a shelter for the two of them in the house by leaning doors he’s removed from the house at a very specific sixty-degree angle and covered with throw pillows.

That they don’t question or laugh at these ridiculously insufficient instructions for surviving a nuclear attack is both darkly funny and anxiety inducing. We know it’s not enough; we know what is coming, and yet we’re helpless to help this couple who are cheerily going about their lives as if it’s just going to be a minor inconvenience for a few days. We know what the back half of the movie is going to be, and their slow demise despite their best intentions is a foregone conclusion. We mourn for them before anything has happened. We want to reach through the screen and save them. Which is why that tiny segment is so pivotal to the film as a whole.

How did these two live through that and come out believing that it was a fun and adventurous time? Even the film undercuts Jim’s daydreaming about reading books by candlelight in his room by showing actual documentary footage of the Blitz as he reminisces in voice over.

And then I stop myself and remember that sometimes, on some bad days, I personally forget how bad the Covid lockdown was. I don’t think I’m the only one. I’ve heard people reminisce about getting to watch movies all day and play games and not have to work. I get it. It hasn’t been even six years yet and there are times I go “Oh man, if I could only go back and do that again,” forgetting, in my privilege, that I didn’t have to worry about much because I could work from home and get paid without having to go out and face it. I forget about the terror I faced as my kids returned to in-person school in the fall. I forget about my anxiety upon entering a grocery store, my need to wipe down the handles of the grocery cart, my nerves going sky high when someone I didn’t know got within my six foot radius bubble. In those moments where I forget, I have to remind myself of the laughable thought that “lockdown wasn’t so bad” is yet another nostalgic lie.

My grandmother was in her 20s when Pearl Harbor was attacked. I wish I had asked her more about what it was like to live during WWII. And then I think about my grandmother’s voice on 9/11, and I think I can hear echoes of what it must have been like. At the time I lived in Washington DC, working as a video producer for Fairfax County Police. My office at the Academy was basically at the end of the Dulles Airport runway, and the National Reconnaissance Office was across the street. We were told to evacuate and get out of the vicinity immediately, which is almost as funny as any advice the government gives to Jim and Hilda, because every other office in the area did the same thing. So all of us ended up sitting on Rt 50 in Chantilly, VA for the next four hours.

The cell phone infrastructure was not what it is now, and I was only able to get one call out. After repeatedly trying to get my parents and tell them that I was ok, I was finally able to reach my grandmother in Wichita. She was relieved to hear my voice and said she would let my parents know I was ok. And then her voice broke and she sobbed “I never thought I’d live to see this again.”

Sometimes it takes a new act of violence to remind us of what it was really like.

I’m writing this in the weeks after Renee Good and Alex Pretti were killed in Minneapolis by Federal agents who are here looking for anyone who is a little “off-white.” I’ve heard more than one person say that they can’t wait for things to “go back to normal,” and I have to wonder when exactly that was. I’ve been hearing that since Donald Trump was elected in 2016. When exactly was “normal”? Was it the 2000s when we were stuck in an endless war in Iraq? Prior to 9/11? How about before the dot-com bubble burst and ended the 90s? Maybe it was before the Oklahoma City and Atlanta bombings? Possibly before the LA Riots? Before Rodney King? Oh yes, before the first Iraq war, right? Maybe before the stock market crash of 1987? How about before the AIDS crisis? We’re back to 1983 now, where we began, with me in bed, listening to the news on my parents’ TV.

That old man wouldn’t blow us all up, would he? Because it sure sounds like he wants to.

That’s what we call the “good old days”?Where The Wind Blows spends a short five minutes graphically showing us that our rose colored glasses eventually turn everything blood red.

Edited by Olga Tchepikova-Treon