| J.R. Jones |

Riot in Cell Block 11 plays on Thursday, February 26th, at the Heights as part of our collaborative series, Down a Dark Street: The Films Noir of Don Siegel. For tickets, showtimes, and other series information, visit trylon.org.

Opened in 1880, about 12 miles north of San Francisco, Folsom State Prison occupies the former site of a mining camp along the American River. The original prison buildings and walls were constructed with hand-cut granite from the surrounding hills, which gives even the most commonplace spaces the look of a medieval dungeon. This, combined with the tall, arched entryways and peaked, Gothic-looking guard towers, has made the prison a potent film location since production was first permitted there in the early 1950s. Movies as various as Michael Mann’s Emmy-winning sports drama The Jericho Mile (1979), Walter Hill’s crime comedy Another 48 Hours (1990), and Edward James Olmos’s LA gang saga American Me (1992) were all shot in Folsom.

Riot in Cell Block 11 (1954), screening as part of the Trylon series “Down a Dark Street: The Films Noir of Don Siegel,” wasn’t the first dramatic feature filmed inside the prison walls—that honor goes to the 1951 Warner Bros. release Inside the Walls of Folsom Prison (the movie that inspired Johnny Cash to write “Folsom Prison Blues”). On one level, the films are hard to distinguish. They share numerous locations, and the camera angles used to capture them are strikingly similar. Both advocate prison reform, and both culminate in riots. Yet Inside the Walls of Folsom Prison, written and directed by Crane Wilbur, unfolds like one of those big-house melodramas Warners used to cook up in the 1930s. Released by the scrappier Allied Artists, Riot in Cell Block 11 was closely patterned on a real-life prison uprising two years earlier, and that authenticity electrifies the action.

The movie’s producer, Walter Wanger, had recently served four months in a minimum-security prison for shooting his wife’s lover and now wanted to expose onscreen the inhumanity of incarceration and the need for penal reform. He found an ideal property in Richard Collins’s screenplay Riot, which was based on the April 1952 rebellion at Michigan State Prison in Jackson, Mich. In that incident, two prisoners overpowered a guard and freed the other prisoners on their wing; the rioters, whose number would swell to 2,600 men, took nine guards hostage and held them for five days, until the warden agreed to publish a list of their demands in the local newspaper. Riot in Cell Block 11 re-creates the major players and nearly every development of this escalating conflict.

Wanger and Siegel scouted the California state prison in San Quentin and the federal prison on Alcatraz Island before arriving at Folsom. “Deputy Warden Ryan showed us a complete, huge two-tier cell block,” Siegel remembered in his autobiography. “It was completely empty with solid iron doors. They had no intention of ever using it. It was absolutely perfect for our picture. No one could get in or out to bother us.”1 Siegel “walked the script” around the prison grounds and helped Collins tailor the action to the available locations; he requested 16 days inside the prison, with inmates to serve as extras. Warden Robert A. Heinze, he writes, was hostile toward the production until he met Siegel’s assistant, the young Sam Peckinpah, whose family was politically connected in Northern California. After that, the crew met with no resistance.

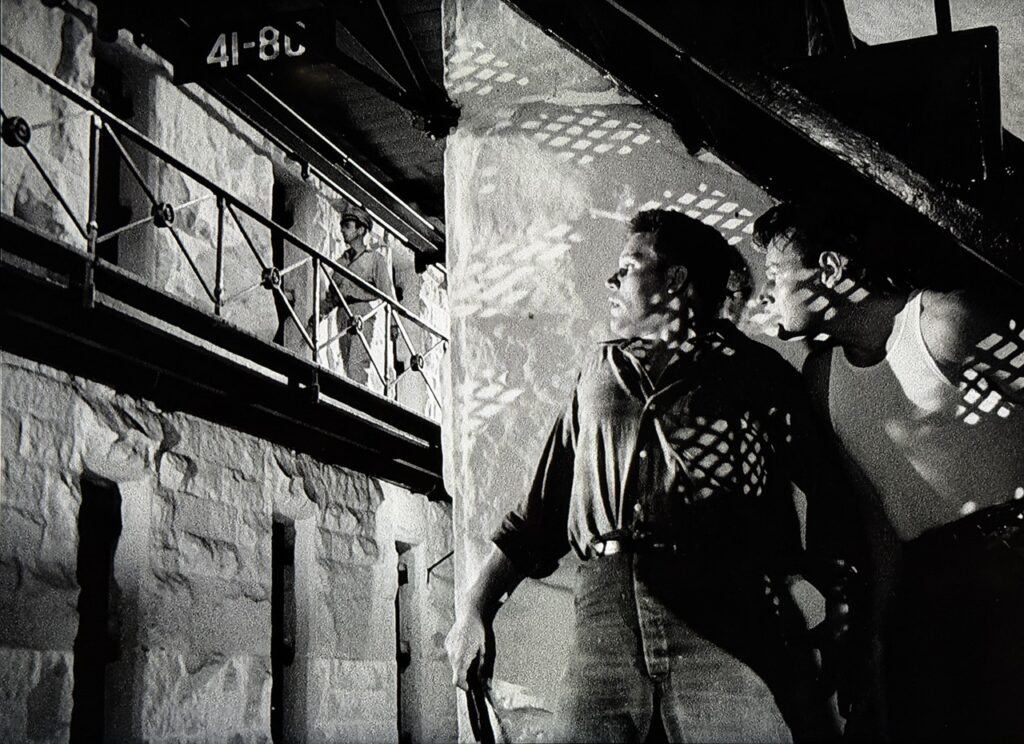

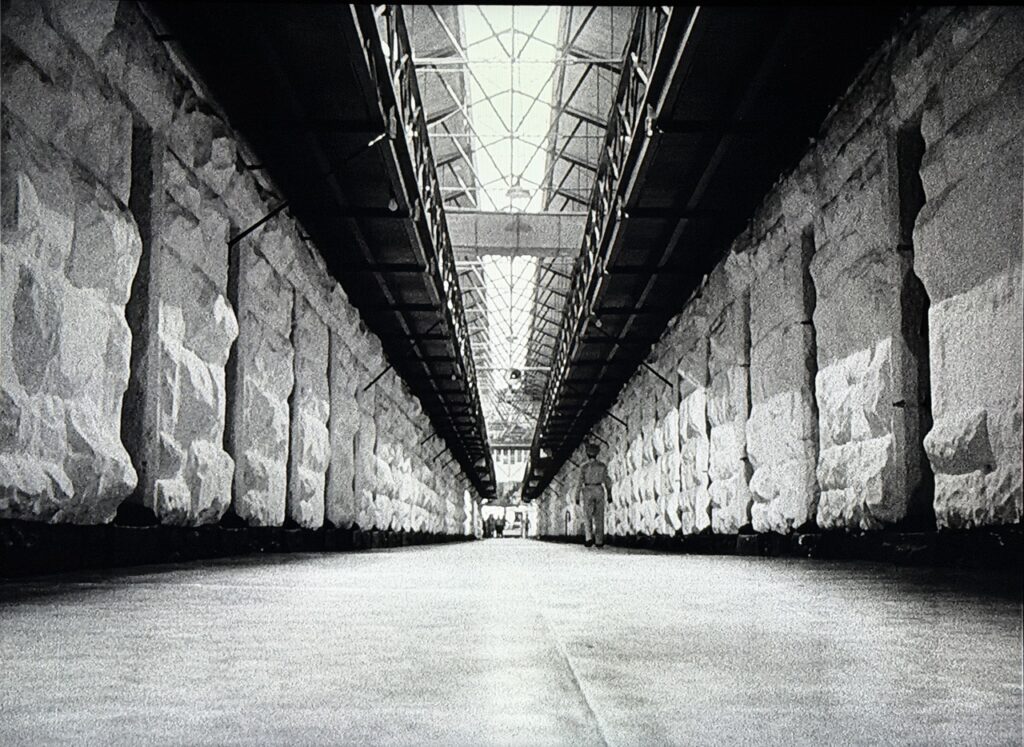

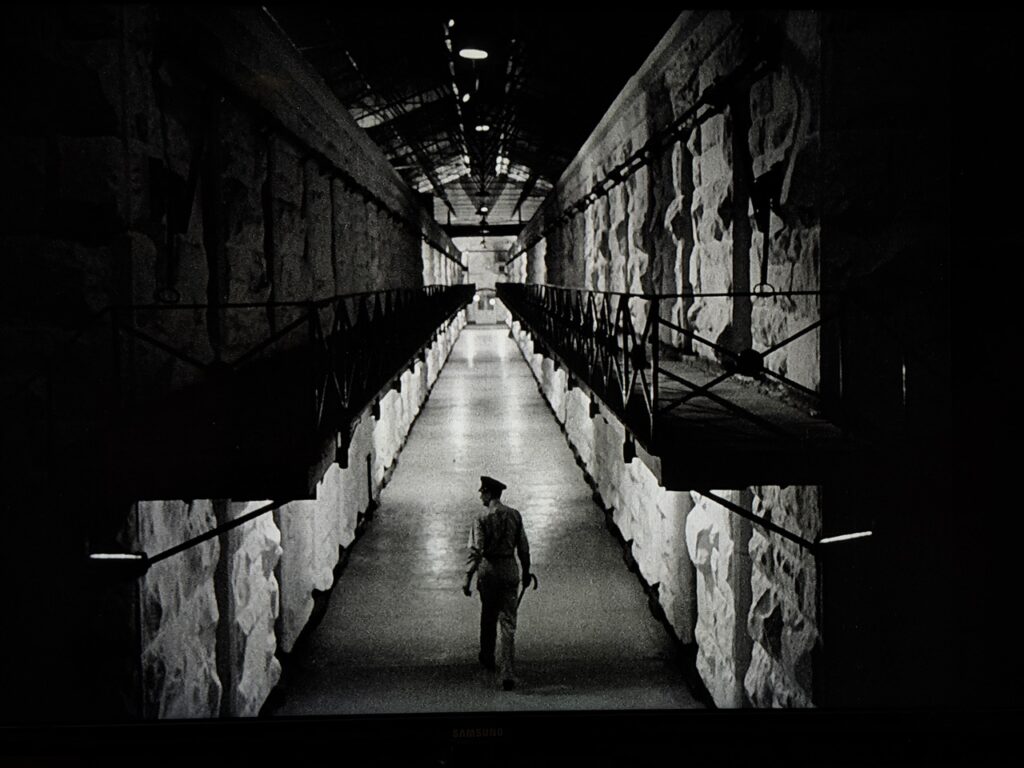

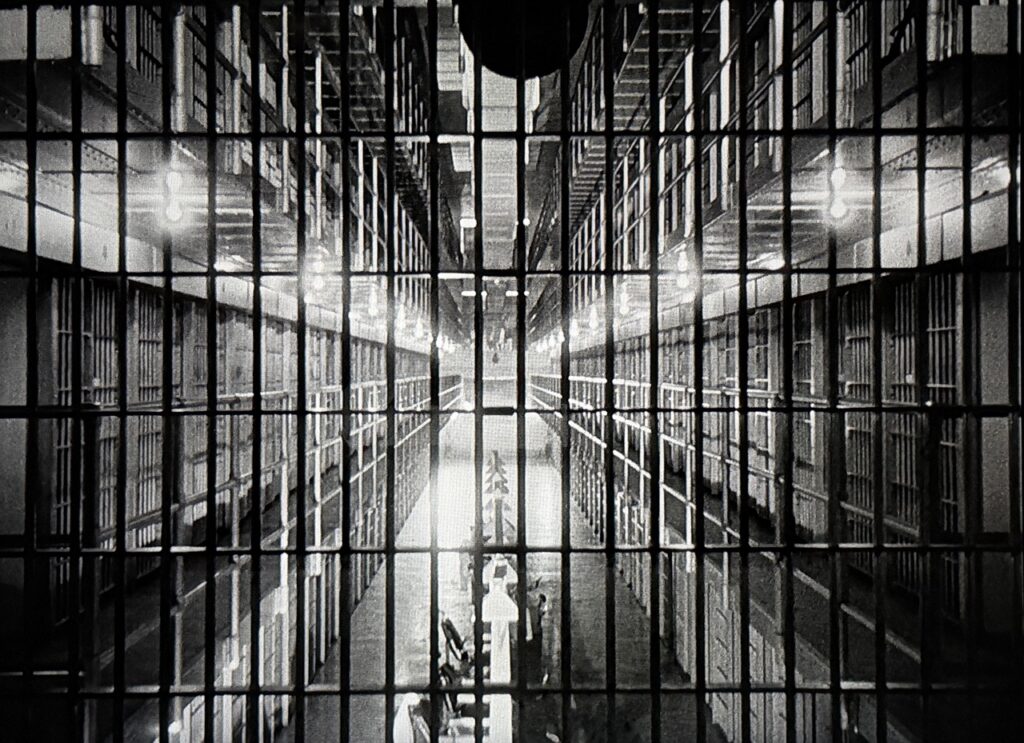

Siegel never mentions Inside the Walls of Folsom Prison, though he got his start directing montage sequences for Warner Bros. in the early 40s (on such Raoul Walsh classics as The Roaring 20s and They Died with Their Boots On) and must have been familiar with the earlier film. The old cell block turns up in both movies, shot from similar angles. Whitewashed granite walls stretch back to a distant vanishing point, punctuated by black steel doors set into the rock. Along either side of this corridor, a black metal balcony with incongruously stylish fencing gives access to an upper tier of cells. An open ceiling exposes a distant skylight down the length of the corridor; in the foreground, where the corridor ends in a large open space, diagonal stairways lead up to the balconies, reinforcing the wing’s symmetrical beauty.

Even if Siegel did lift this shot from Inside the Walls, he makes more kinetic use of it than Wilbur does. When the prisoners are freed from their cells, the wing explodes: prisoners on the upper tier empty their cells of everything, tossing garbage, sheets, mattresses, shredded pillows and bedframes over the fencing and onto the floor below. Near the end of the movie, as the rioters await word that their demands have been met, Siegel cuts to a close-up of a ringing phone on a desk in the cell block; the camera pulls back to a deep-focus long shot of the symmetrical wing reaching back into the distance. The rioters rush into view at the distant end of the corridor and race en masse toward the camera, all the way up the wing, until they fill the frame and their ringleader, Dunn (Neville Brand), snatches the receiver from the phone set.

The movie is dominated by ugly images of control. The cell doors are nightmarish—thick, black metal slabs with a six-inch slat at eye level and columns of air holes running down to the floor. A big horizontal bolt slides across it, and a heavy padlock completes the lock-in. The cell block entrance where Dunn negotiates with Warden Reynolds (Emile Meyer) is a welter of fence posts, chain-link, diagonal reinforcement bars and, behind all these, a tall, slatted steel gate leading inside. The vast mess hall, with its whitewashed granite walls and large, elevated windows, offers some light and relief, but even here, the prisoners at their long tables are caged in with a tall chain-link fence.

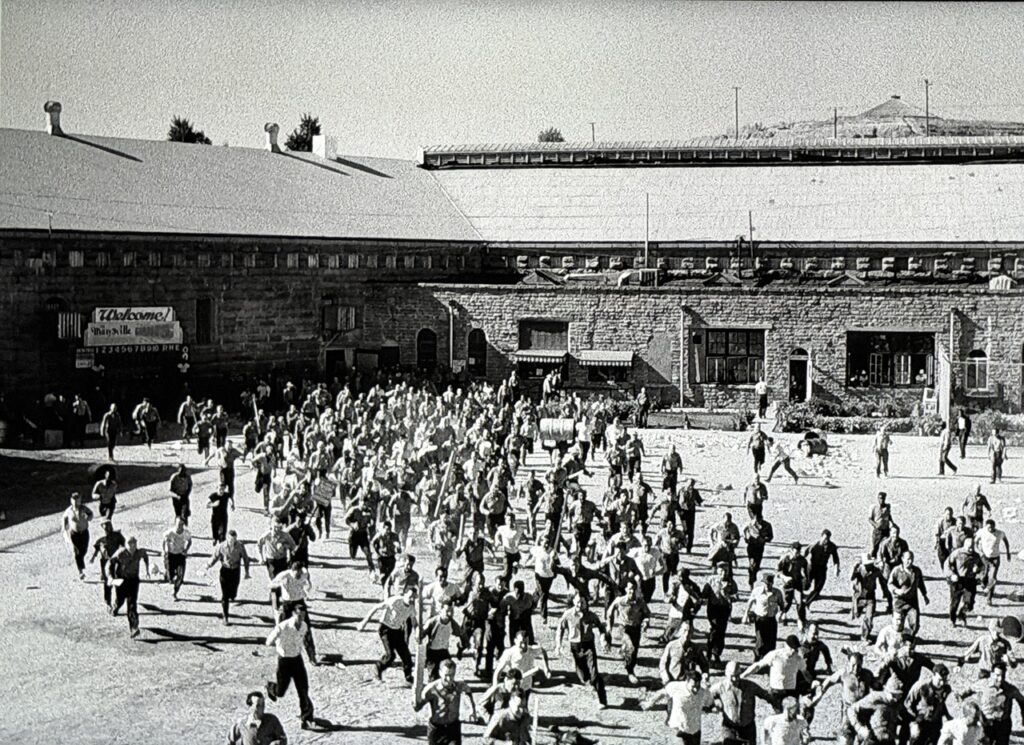

Folsom Prison consists of five cell blocks and two mess halls ringing a huge central exercise yard, which provides Siegel with another choice canvas for his images of rigid control and wild abandon. Early in the film, a shot from inside a guard tower reveals a line of men marching right to left across the yard as they head from their cell block toward the mess hall in the main building. In another high-angle wide shot, prisoners gradually divide the frame as they march single-file from the main building down to their cell block. Siegel uses a nearly identical angle on the yard after the insurrection has spread to cell block 4 in the mess hall and hundreds of prisoners pour out of the building, running amok.

Inside the Walls gives a more comprehensive sense of the prison, with scenes set in its shoemaking shop, canning plant, and rock quarry. It shows the tall, arched entryways where arriving cars are screened before being admitted to the prison grounds, and the vertically collapsable ladders that lead from the exercise yard up to the trap doors of the guard towers. But Inside the Walls tells a familiar story, pitting a vicious, cigar-chomping, Stetson-wearing warden against a compassionate, pipe-smoking, psychology-minded captain of the guards. Not one but two subplots recycle the old prison-movie cliché of a squealer who sticks his neck out for the authorities but learns that they can’t protect him on the inside. Worst of all, the story is framed by portentous voice-over narration from the prison itself. “I am Folsom Prison,” it intones during an opening montage. “At one time they called me Bloody Folsom.”

This sort of hokum was exactly what Wanger and Siegel wanted to leave behind. Their Warden Reynolds is a conscientious professional who’s spent years lobbying the state for the same reforms his prisoners are now demanding. Their complaints, distilled from the Michigan riot, reflect the precise ills then taxing prisons across the U.S.: overcrowding, lack of productive work for prisoners, mingling of mentally ill offenders with the rest of the prison population. The gradual escalation of the riot, copied from real events, is persuasively messy, complicated by state politics and a hungry press corps. Folsom State Prison may play itself in both movies, but through the power of story, it seems like two entirely different characters.

Footnotes

1 Don Siegel, A Siegel Film: An Autobiography (London: Faber and Faber, 1993), 160-61.

Edited by Olga Tchepikova-Treon