| Jay Dizter |

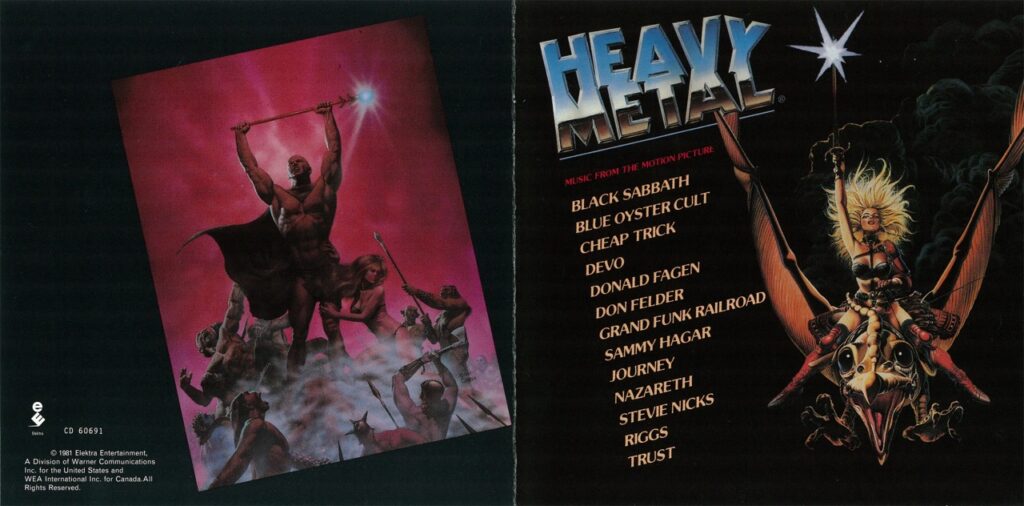

The cover of the Heavy Metal soundtrack album featuring Den and Taarna. The good news: Both characters appear in the movie. The bad news: The cinematic renderings operate at a much different level of skill and realism.

Heavy Metal plays at the Trylon Cinema from Friday, February 27th, through Sunday, March 1st. For tickets, showtimes, and other series information, visit trylon.org.

The reputation of the animated cult classic Heavy Metal rests on promises it largely can’t keep. Sure, it’s full of sex, drugs, and rock ’n roll, at least superficially. What it actually delivers is something more revealing. The film is deeply of its era, which is both a strength and a weakness. Paired with its killer soundtrack, it becomes a glossy (but not too glossy) artifact of contemporary cultural conventions wrapped in sci-fi fantasy and classic-rock swagger.

1. The Memories

For me, Heavy Metal is a hodgepodge of sound, images, nostalgia, and puberty—proof that movies and music can fuse into a formative experience even when the thing doing the forming doesn’t live up to your expectations. I didn’t discover it as a critic or a cinephile; I discovered it the way it was meant to be discovered: semi-furtively on cable television.

This was the early 1980s, smack-dab in the middle of the slasher-movie boom, and HBO had a habit of premiering horror, science fiction, and genre-adjacent movies, aka “the good stuff,” on Friday nights. My mom worked at a bank and had to stay till 8 or 9 p.m. on Fridays, which meant my dad was in charge. This created a small but meaningful loophole in the R-rating firewall: the “Uh, don’t tell your mom I let you watch this” clause. Through it, I saw plenty of cynical, slapdash garbage that was made to cash in on the slasher craze, but also genuinely great films like Halloween, Alien, and Blade Runner … and also Heavy Metal, which I thought my parents might nix given that the movie’s promo materials focused on Taarna, the scantily clad, mutant-bird-riding warrior princess (when battling evil warlords to the death, you really want as much exposed flesh as possible). But because Heavy Metal was animated, a silly little cartoon, I was in the clear.

I remember sitting in the flickering glow of the TV,1 completely captivated and half-terrified that my dad would barge in (during a sex scene, undoubtedly) and shut it off. At the same time, I couldn’t ignore the uneven animation and the sense that the film was pandering to an audience that loved the same things that I did—science fiction, fantasy, comics, animation, and rock music—but for all the wrong reasons. Still, the combination of cool songs and sheer spectacle cemented itself in my memory in a way no other Friday-night HBO premiere had.

Black Sabbath performing live during the “Mob Rules” tour. I know this because Geezer Butler is seen playing a B.C. Rich Eagle bass. Told you I was a music nerd.

2. The Music

Did I mention I was also a music nerd? I was every kind of nerd except the kind who gets good grades and college scholarships. Around the same time HBO infiltrated our household, I won a “six-pack” of albums from KC 103, the local AOR radio station.2 One of those LPs was Heavy Metal: Music from the Motion Picture,3 which fused the movie and the soundtrack in my brain. For me, they’re inseparable, a warm and fuzzy memory of media synergy before “media synergy” became soulless corporate jargon.

One important thing to know: Neither the source comic magazine—an American licensing of France’s Métal Hurlant (roughly “Screaming Metal” or “Howling Metal”)—nor the movie, nor the soundtrack, has much to do with the identically named musical genre.4 While Black Sabbath is on the soundtrack, so are Devo and Journey. The title suggests “headbanging” but what you get is an extremely 1981 sense of what “rock music” meant, capturing a moment when hard rock, prog, new wave, jazz-rock, radio-friendly AOR, and yes, even the occasional blast of heavy metal all coexisted on the same FM bandwidth.

What stands out to me as an adult is the album’s sequencing. It moves fluidly between songs that announce themselves assertively and tunes that settle into a more nocturnal groove. Black Sabbath and Blue Öyster Cult provide menace, but they’re balanced by the sleek sophistication of Donald Fagen and the kooky mysticism of Stevie Nicks (“I’m no enchantress,” she bleats on “Blue Lamp”—tell that to the rest of your catalog, Stevie). This contrast gives the soundtrack its personality: it’s tough without being too horribly macho and polished without feeling overproduced. You can call it “dad rock” or “boomer-core” or any other backhanded appellation you like, but the music works wonderfully in the context of the film.

Appropriately enough, the album kicks off with Sammy Hagar’s soundtrack-exclusive “Heavy Metal,” a song whose lyrics are about… the musical genre. I know a lot of people view Mr. Hagar as the man who instigated the long, slow decline of Van Halen and the epitome of mediocre cheese, but this song is more than mediocre; I say it’s one of Hagar’s best, having never listened to any of his albums and knowing only whatever Hagar tunes KC 103 happened to play.

For the Hagar-adverse, there is finer fare nestled deeper within the track listing, including Devo’s goofball cover of “Working in the Coal Mine” and Nazareth’s brooding “Crazy (A Suitable Case for Treatment),” but there are also some bona fide collector’s-item classics as well, such as the alternate version of “The Mob Rules” by Black Sabbath that’s guaranteed to peel the gingivitis off your grandma’s dentures.5 Same band, same song, but the version here is an earlier take that’s rawer and more in-your-face than the one they recorded later for their Mob Rules LP, topped off by a typically powerful vocal performance by Ronnie James Dio—yes, I know for Sabbath purists it’s Ozzy or nothing, but the Dio years were full of brilliant songs.

You also get not one but two Cheap Trick tunes that are available nowhere else in their catalog. The first one is “Reach Out,” a bouncy number with a distinctive synthesizer hook (this was when the band was flirting with new wave affectations), a glossy little earworm that happily stays in your head for the rest of the afternoon. The second Cheap Trick selection on the soundtrack is “I Must Be Dreamin’,” which rides the synthy trend before descending into something more propulsive and much darker. “Reach Out” was released as a single from this album, with “I Must Be Dreamin’” as the B-side. Now that’s good synergy.

Of further possible interest for completists are the two tracks by Don Felder, who was fresh off the breakup of the Eagles and exploring his solo options. If you’re not Jeff Lebowski and thus irrevocably hostile to the Eagles, Felder’s “Heavy Metal (Takin’ a Ride)” sees a partial reunion of that band, with Felder joined by Timothy B. Schmit and Don Henley for a tune that rocks as hard as the Eagles ever did (“Life in the Fast Lane” excepted).

Now the worst track is hands down Journey’s schmaltzy ballad “Open Arms.” While I can acknowledge that the band members are all talented musicians, I never really cottoned to those guys and I especially didn’t care for their ballads. Plus, did you ever see the Journey episode of Behind the Music? Steve Perry is a dick.

The occasional saccharine moments aside, there’s a strong sense of texture here. More than a few of these tracks linger rather than exploding: case in point, Donald Fagen of Steely Dan’s “True Companion,” a dry run for what would become his first solo album, The Nightfly. “True Companion” understands mood as well as momentum, spending a full three-and-a-half of its five minutes noodling and grooving before the vocals kick in.

What makes this soundtrack endure is how effortlessly listenable it is. You don’t need nostalgia for the film, or even affection for early 80s rock radio, to appreciate how nicely these songs play together. It’s the album’s refusal to be boxed into a single genre that invites repeat listenings. The soundtrack is definitely more sophisticated than the movie and a reminder of a period when mainstream rock could be adventurous, stylish, and occasionally weird in all the right ways.

Heavy Metal: Music from the Motion Picture may stand on its own, but it was, of course, meant to work in tandem with the film. Revisiting where a few of the songs actually land in Heavy Metal reveals both the film’s best instincts and its most obvious limitations.

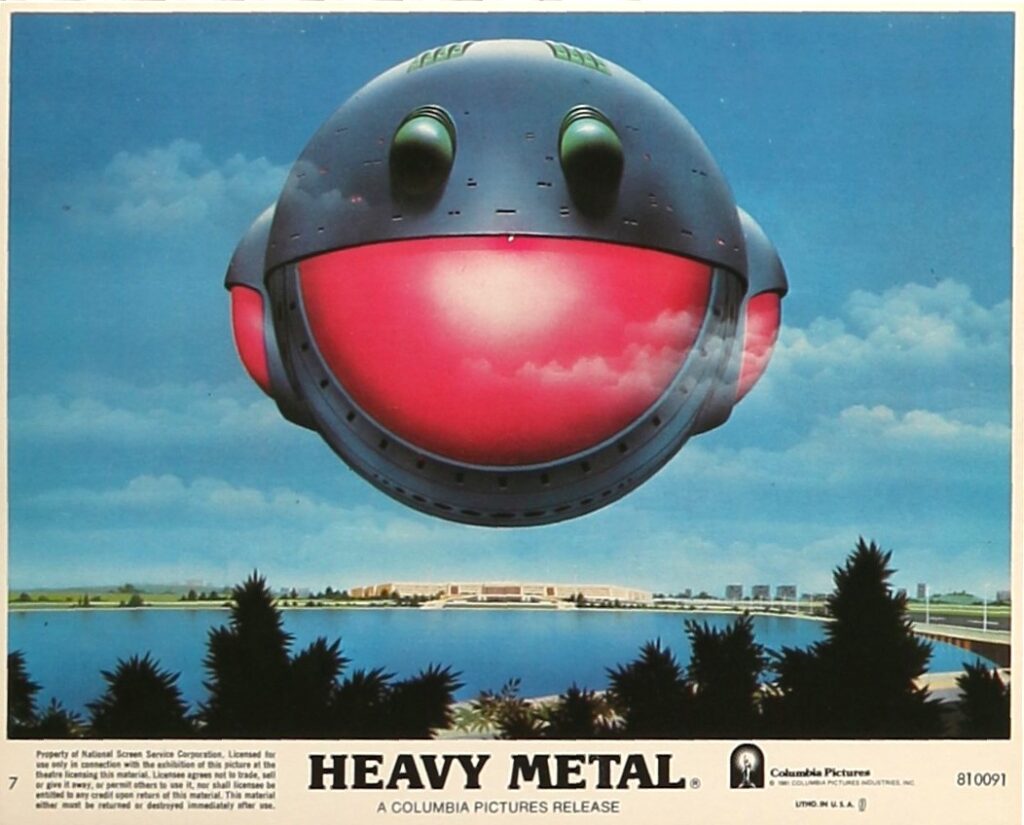

Publicity still of the space cruiser from the “So Beautiful & So Deadly” segment looking like an interplanetary emoji with docking privileges.

3. The Movie

Released in August 1981, Heavy Metal occupies a strange niche in pop culture: not quite a great film, not quite a mere novelty item, this collision of animation, sci-fi fantasy, rock music, and carnality could only have come from that moment in time. The movie assembles several loosely connected segments into a cosmic anthology, all threaded together by the glowing green Loc-Nar, the self-proclaimed “sum of all evils” and a malevolent change agent that drifts from story to story.

What people tend to remember first is the attitude. Heavy Metal sold itself as rebellious in an era when “animation,” with very rare exception, meant either Disney or Saturday-morning TV—safe and child-friendly. Seeing a cartoon that mixed violence, sexuality, humor, and rock music felt cool, even if the film’s idea of adulthood now looks fairly juvenile. Its provocation is earnest: it wants very badly to be sexy, funny, and cosmic.

Structurally, the anthology approach works in the film’s favor. Segments like “Den,” with its sexualized fantasy setting, and “Taarna,” the most traditional sci-fi segment of the bunch, give Heavy Metal its most enduring images. The stories move between satire, horror, and adventure without settling into a single tone, which keeps the film lively even when individual moments falter. At the same time, the looseness doesn’t feel intentional; it seems like an unwanted yet inevitable by-product of the low budget and time constraints under which the movie was put together.

Case in point: “Harry Canyon,” the first proper story in the film. (And yes, the hero’s name is “Harry Canyon,” which any red-blooded 14-year-old would immediately recognize as the kind of double entendre the film knew exactly how to exploit.) Mr. Canyon is a cab driver in the grimy New York of 2031 who picks up a beautiful fare on the run from alien gangsters trying to steal the Loc-Nar from her. The woman faints, because women always be fainting, and Harry takes her back to his apartment, where they have sex—while “Open Arms” plays in the background, naturally—and then decide to sell the Loc-Nar to the gangsters with typical film-noir results. It’s also the most music-heavy segment, utilizing Blue Öyster Cult, Fagen, Nicks, and Riggs in addition to the Journey track.6

When I say that some of the animation in Heavy Metal looks crude, imagery from “Harry Canyon” is what usually pops into my head. Although the segment is rendered in an allegedly realistic style, the gangsters look half-finished, characters’ heads grotesquely change shape mid-scene, and Harry himself occasionally looks like an anthropomorphic dog. Having recently watched René Laloux’s The Time Masters, with its storyboards and character designs by French comics master Mœbius, the stylistic resemblance jumps out. Although heavily (and obviously) inspired by Mœbius, “Harry Canyon” isn’t his work, but it’s the same aesthetic that would be revisited years later in The Fifth Element, a film featuring a cynical taxi driver with a flying cab who gets involved with a beautiful redhead—except Mœbius actually did work on that movie.

Then there’s “Den,” based on artist Richard Corben’s Neverwhere series. The Loc-Nar whisks an adolescent nerd to another world, where his scrawny frame is magically upgraded into that of the impossibly muscular warrior Den. He’s immediately dropped into a power struggle between a queer-coded immortal “supreme leader of the revolution” and a voluptuous queen, complete with battles, seduction, and a finale in which Den rides off on a giant dragonfly with a fair maiden. In other words, classic adolescent male wish fulfillment.

Corben’s style sits between realism and fantasy exaggeration: swollen muscles, lacquered skin, airbrushed lighting, and women with huge tits. On the page, his idealized pneumatic figures create a lurid, tactile effect best exemplified by his cover for Meat Loaf’s Bat Out of Hell album. On the screen, however, his style was never going to survive Heavy Metal’s bargain-basement animation, which can’t reproduce the texture and weight his work is built upon. The animators try to mimic Corben’s highlighting, but without any heft behind them, the characters wind up looking as if someone painted reflections onto anatomically correct rubber dolls. Also, this segment features no music from the soundtrack.

The sequences that work best in Heavy Metal are the humorous ones—elastic Looney Tunes–style animation is much easier to appreciate when it isn’t forced onto supposedly serious drama. Take the “Captain Sternn” chapter: Sternn is chased through a space station by the hulking Hanover Fiste over Cheap Trick’s cheerful “Reach Out,” a sequence that recalls those classic Scooby-Doo chases where the gang is pursued—hilariously!—by the monster of the week to some generic pop-rock backing. The absurdity and musical punctuation align perfectly, making it one of the film’s most successful tonal shifts.

Visually, Heavy Metal is both imaginative and uneven. There are moments of striking design and atmosphere, especially in the backgrounds and establishing shots, but the animation itself often betrays its budget and schedule. Character motion can look stiff, particularly when compared to the lush style the film clearly wants to project. As a kid, I was dying for an R-rated Fantasia with spaceships and guitar solos, but unfortunately, you can plainly see where the movie’s ambition outpaced its resources.

Then there’s the film’s obsession with sex, which is impossible to ignore. Nudity and innuendo are everywhere—sometimes it’s playful, sometimes it’s funny, and sometimes it’s just gratuitous. The movie equates “adult” with exposed flesh in ways that feel dated now, and it occasionally shoots itself in the foot by pausing to leer at it: “Comics and animation can be used to tell sophisticated, complex adult stories; they’re not just for children. Also, LOOK AT THE BODACIOUS TA-TAS WE GAVE THIS CHICK!” Even at 14, I felt a little insulted. All that gratuitous nudity seemed to pander to the audience’s id while inadvertently confirming what my parents wrongly suspected was the only reason I wanted to watch R-rated movies.

Nowhere is this more obvious than in “Taarna,” a fantasy segment in which the eponymous beautiful warrior rides her mutant bird through a post-apocalyptic landscape meting out brutal justice to mutant barbarians. Interestingly, the character is mute, a choice that, intentionally or not, caters to the type of dudes who prefer their women silent and decorative. The segment’s impact is strengthened by its soundtrack: Black Sabbath’s “The Mob Rules” is masterfully deployed to punctuate the action, while Sabbath’s “E5150” and Devo’s “Through Being Cool,” neither of which are on the official LP, give the chapter additional texture. It’s still impressive visually and the action makes for operatic spectacle, but the heroine’s silence underscores how Heavy Metal often mistakes objectification for storytelling and knows exactly which audience it’s peddling to.

Still, Heavy Metal is worth a look not because it’s a quote-unquote classic but because it throws itself at animated spectacle with shameless enthusiasm. The film is adolescent and occasionally dumb, yet it’s that combo that makes it worth revisiting. Coupled with a soundtrack that often does more heavy lifting than the visuals, Heavy Metal is an artifact of a moment when animation tried to grow up by being raunchy instead of smarter. Watching it now, I don’t see the R-rated Fantasia I once (perhaps foolishly) hoped for so much as a movie reaching for something bigger than its budget, talent pool, and taste level could pull off. Heavy Metal, despite its claims of being “for adults,” still managed to leave a mark on its true audience: 14-year-olds sitting too close to the TV on a Friday night.

Footnotes

1 Watching Heavy Metal on TV gave new meaning to the phrase “boob tube.”

2 If you’re curious, the rest of the six-pack included Foreigner’s 4, Billy Squier’s Don’t Say No, Triumph’s Allied Forces, Blackfoot’s Strikes, and Rush’s Exit… Stage Left. Six albums total, but with two double-record sets in the pack, I actually scored eight albums.

3 The movie also has a fine score by Elmer Bernstein; in the interest of keeping this article under 5,000 words, I won’t delve into it.

4 No idea why the American version went with “Heavy Metal,” as both “Screaming” and “Howling” sound way cooler to my ear.

5 Credit to Doug Shawhan for that line.

6 Riggs was a competent if unremarkable AOR band with two songs on the soundtrack, aided by the small detail that they were signed to the label that released Heavy Metal: Music from the Motion Picture.

Edited by Olga Tchepikova-Treon