| Lucas Vonasek |

Demolition Man plays on glorious 35mm film at the Trylon Cinema from Friday, April 25th, through Sunday, April 27th. For tickets, showtimes, and other series information, visit trylon.org.

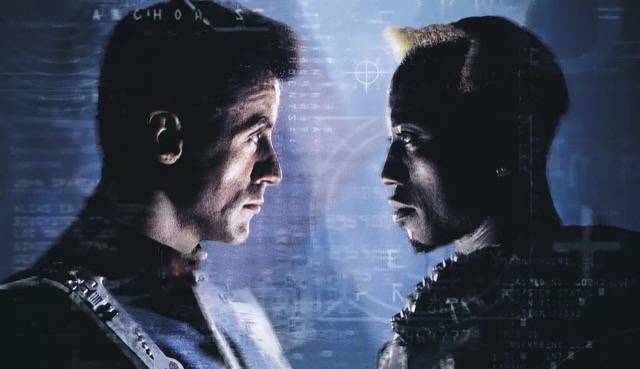

Fascism can take many forms. Throughout books and movies, it is often portrayed as overt and obvious villainy where injustice drips from the pronounced canines of the antagonist. Other times, fascism can be seen as a devilishly debonair individual smoothly stringing together words of putrid pearls that the masses of followers mindlessly cheer without question. In Demolition Man (1993), starring Sylvester Stallone and Wesley Snipes, fascism reveals itself under the guise of false progress by way of technology and a holier-than-thou doctor turned technocratic dictator.

Crass, bullheaded, misogynistic and enough steroids coursing through his veins to make your biceps twitch just watching him, John Spartan (Stallone) is the film’s flawed hero. He is a man out of time—a relic of a bygone society that couldn’t right itself. Even in the operational parameters of the then Los Angeles Police Department, he played by his own rules to get the job done even if the price was the lives of innocent bystanders. His counterpart, Simon Phoenix (Snipes) is nearly his equal in every way, but while Spartan wants order and justice, Phoenix wants freedom of individuality by way of anarchy. Two “maniac” characters running down parallel paths can unintentionally have barometric properties of foreshadow for us as audience members living in a society that is slowly feeling the fascist grip tighten by the day. So, while undoubtedly flawed, can the characters of Demolition Man of the past help inform on how to combat technocratic fascist governments? To answer that question, we first must examine life in the fictional San Angeles of the not-too-distant year of 2032.

“I find this lack of stimulus truly disappointing.”

A massive earthquake swallowed nearly all of Southern California and its culture with it, giving way to societal change. A change that gave way to people forgoing traditional toilet paper for the three seashells, elevating Taco Bell as the only restaurant available, listening to commercial jingles, and living under the watchful eyes of a techno-big brother. When we first meet Lt. Lenina Huxley (Sandra Bullock), a cop in the San Angeles Police Department, who is also Spartan’s guide (and therefore, the audience’s guide) through the reality of the future, it is quickly revealed that all speech and behavior is intensely monitored by a type of an omnipresent technology that fines individuals for violating the “verbal mortality statute” whenever they curse—unequivocally revoking freedom speech while erasing personal privacy.

While characters in 2032 certainly don’t enjoy these fines, it is tolerated by them. Their vocabulary has become dry, robotic and nauseatingly cheesy. They are led by Dr. Raymon Cocteau (Raymond Hawthorne) who described as a visionary and a savior. Cocteau is responsible for the entire technological integration throughout society. He stands unchecked with a self-indignant hubris that can only come from a person that craves absolute control. He wields unchecked power over a people that either know how turbulent the past was and don’t wish it to return or they have never experienced anything else and don’t know any other kind of life. Dr. Cocteau is the fascist figurehead of the film and people are either afraid to challenge him or they simply are unwilling to upend the status quo. The only people who are willing to challenge him are the people who remember what life was like before the sweeping and steady erasure of personal freedoms and expression.

“What seems to be your boggle?”

One of those people is Dr. Cocteau’s chief rival is Edgar Friendly (Dennis Leary). Friendly is the leader of a literal underground resistance community that is the last bastion of holdouts against the technocratic fascist regime of Dr. Cocteau. They are full of life and vibrant with diverse languages and cultures and know how to make a mean rat burger. Friendly states the desires to “smoke a cigar the size of Cincinnati” because he believes that life and freedom should always be in tandem. Most importantly, what Friendly and his underground community represent in the fight against fascism is hope. Hope is their fuel and that one day their long night will end, and the metaphorical sun dawn a new day. This community is the enduring heartbeat that is needed against such a powerful figure and a society encased in a fascist grip.

“Send a maniac to catch one.”

Another person who remembers life before is the film’s antagonist, Simon Phoenix. He is thawed and released into a new world to hunt down Edgar Friendly. He’s immediately demonized and hunted for his actions. However, it’s revealed within the film that Phoenix was thawed and programmed to be Dr. Cocteau’s pawn, to bring mayhem to placidity and further Dr. Cocteau’s controlling grip over the populace. Purposefully stoking fear and claiming yourself as the savior when that fear is subdued is a page ripped from the basics of fascism.

Phoenix represents anarchic change in a world that is devoid of any real pushback against the powerful. He is symbolic of a voice that is now lost amongst the people of San Angeles. A rageful voice that screams of muted personal expressions and inequality. While Phoenix may be an ethically flawed character within the film, so is the film’s protagonist, John Spartan. They both approach their new reality in similar and different ways.

Spartan not only introduces a slew curse words throughout San Angeles, but he also introduces rebellion and personal responsibility within the San Angeles Police Department. From the moment he thaws, he questions authority and suspicious of the technology surrounding him. He is seemingly also the first one to outright oppose Dr. Cocteau’s methods. He rebukes the cryo-penal system, calling it inhumane to have people frozen with their thoughts decades on end. He unflinchingly expresses himself in whatever manner he wants. He does all of this in front of Lt. Huxley who over the course of the film realizes the society around her and becomes more and more radicalized in small, but meaningful ways. As Spartan routinely displays his distaste for authority both verbally and physically, Huxley attempts to use 20th century slang, like “You matched his meat!” and “You really licked his ass!” With this, Huxley starts to openly defy the verbal morality statute that is put in place throughout San Angeles. While they are humorous moments in the film, they’re also touchstone moments for her because with every cruse word she defiantly utters, she is slowly beginning to aide in crumbling the façade that Dr. Cocteau has created. All steps in combating fascism, whether they are small or large, are important steps because they add to the momentum of overthrowing the sitting regime and that’s what Huxley stands for in this film—the progress made by the people under fascist rule. While Huxley is representative of the people’s progress, so is Spartan. He is also representative of a change within a broken system, i.e. the San Angeles Police Department. Whether he realizes the clout he has in being a legendary 20th century figure or not, the way he carries himself has a positive ripple effect among the people of 2032. They see the power that one individual can possess, and, in turn, how powerful people can be when they band together, use their voices, and if necessary, their bodies to fight fascism.

Demolition Man is not that much of an exaggeration of how times can turn for the worse. Technology is on a trajectory that infringes on human creativity, expression, and necessity. The federal government is continually stripping away the rights of people and replacing them with authoritarian agendas. We may never be frozen for decades and have to use the three shells in the bathroom, but it could get worse than it already is. And if it does get worse, we’ll need every Edgar Friendly, Simon Phoenix, and John Spartan to overcome it because after all, fascism can take many forms, but so does rebellion.

Edited by Olga Tchepikova-Treon