| Phil Kolas |

Ghost Dog: Way of the Samurai plays on glorious 35mm at the Trylon Cinema from Friday, May 16th, through Sunday, May 18th, as a collaboration with the Cult Film Collective. For tickets, showtimes, and other series information, visit trylon.org.

A Moral Interrogation of Cultural Appropriation & Judgements Thereof

One of the greatest and most delicious irrefutable gifts of the internet has been the ever utterly overwhelming and bottomless wash of media that is our every waking hour. Beneath every rock there are hidden worms—snacks that will sustain our artistic intellect. Algorithmic suggestions have led to no less than a dozen new favorite bands for me to blindside my friends with and reign supreme in my taste when I bring them things they haven’t heard of yet which blows their ears off just as much as they did to me, but I’m better than them because it happened to me first. You’re welcome, Eric.

But what about the other bits and pieces before those? What of the works and such that can be declared derivative, pablum, mediocrity? What of the trash we use to climb that mountain of aesthetic greatness? Do I owe The Last Samurai a thank you card for eventually having led me to Seven Samurai, Lone Wolf & Cub, Zatoichi, and Ghost Dog? I mean, yeah, obviously, but I’ve got 1300 words left to try to convince you that I’m right.

First, a note my heart tells me is worth a diversion: I’m aware the last thing the world needs is another several paragraphs from a white dude about what does or doesn’t count as cultural appropriation, but this is the topic at hand that’s gripped my muse for this month’s installment of “Free Movie Opinions from a Philosophy Major That’s Worth $Free,” and all I can say is that I hope you’ll bear with me until the end. Writing is fun, almost as much fun as reading is, and you should get to the end, if for nothing else than for the mental Double Dare challenge of it all I just threw down for you. I’ll lay down the law right now and say, yes obviously Halloween costumes are offensive if you’re dressing up like any culture—costumes are either a joke or a horror by definition—there’s no respectful way to wear a caricature of another human being. The zero thousand dollar question of this essay, however, is: are there entire art forms that can only be appreciated, enjoyed, or created “the right way” by “the right people”? Again, I say no, but I feel like this Ghost Dog movie created by a white dude about a black character using Japanese literature so he can work for an Italian mob boss seems like a good place to start.

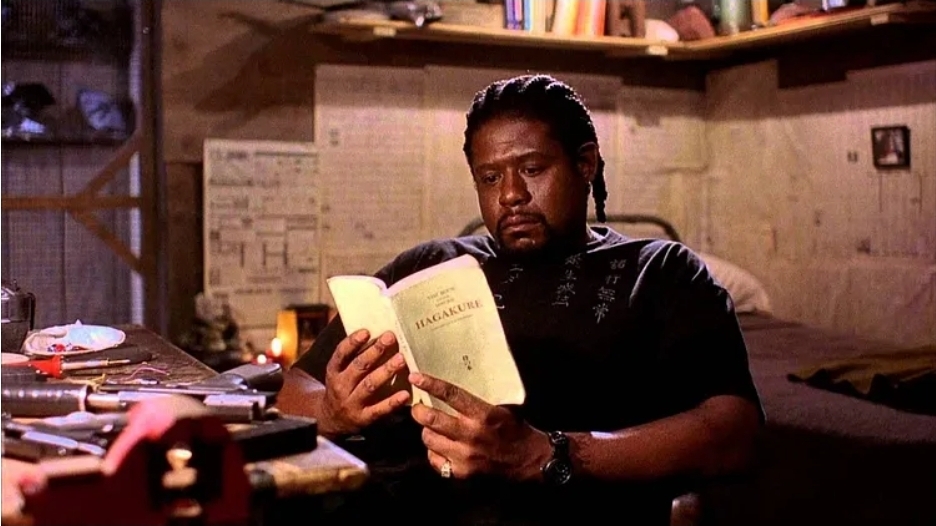

Let’s go ahead and safely assume that a 18th century writer of a Japanese warrior how-to booklet like the Hagakure could not have possibly predicted it would end up in the hands of black man in an urban jungle who raises pigeons on a roof (I’d never met the authorial man in question from 300 years ago, but I bet he wouldn’t have predicted movin’ pictures either, so that all goes without saying). Just to immediately flip the coin—do you think H.P. Lovecraft could have predicted (or would have wanted) his CTHULHU stories to inspire a Japanese metal band like Ningen Isu, or a black sci-fi television show like Lovecraft Country? I can guarantee you that he would not (pro tip: do not google search what Lovecraft named his cat). Does white man Jim Jarmusch get a green light to make a movie with a black protagonist just because he asked RZA of the Wu-Tang to do the soundtrack? Maybe. Or maybe it’s like the World’s Greatest Author Chuck Tingle said; “Once an artist puts their art into this timeline it begins to change and bloom and grow in unexpected ways. That is the wonderful thing about the trot of a writer or painter or director buckaroo.” Do you think the Shaw Brothers planned on making all those Kung Fu movies just so RZA could use the sound effects and factually incorrect English language dubs made for American movie theaters in order to make hip hop beats? Have I made my point sufficiently with this many insufferable self-referential looped-back-in examples? It is all just art making art from art, which is the only way to ever make art (It gets extra twisted when you think about things like how mafia gangsters never started kissing each other’s rings until The Godfather II did it first and then they stole that ice-cold move from the movie into real life, but that’s another Ouroburous metaphor for another essay).

To lead back again to The Last Samurai, I am aware it is not a Great Movie. Did it absolutely blow my hair back when I saw it in theaters when I was 19? Of course it did. I am many stupid things but a liar is not one of them. It did not make me a Tom Cruise fan, but it did make me a samurai fan. Did I do that right? Did my inhalation of Kurosawa movies in my twenties somehow karmically redeem Edward Zwick? That seems a bit impossible and preposterous to try and measure, but somewhere in our media judgment, there must be a place for the Remedial Introductory Text. Whether it be in books, movies, plays, music—every new generation needs to be communally shepherded after that first unavoidable and bland introduction, not shamed for falling for simplicity first. Everyone is a child first. Simplicity is just the introduction. The aperitif. “Did you like that? Pretty great, wasn’t it? Well you’ll love this.” You can’t just start a kid on Sword of Doom and then call him a poseur because the ending made him cry. It’s nightmare fuel. There’d be no appreciation, and they’d sour to the beauty.

There’s a wonderful scene in this film, when Ghost Dog is comparing literature with a little girl (who keeps her books in a lunchbox because books and art are literal sustenance DEAL WITH IT) because Jim Jarmusch knows and shows—not only by the pure act of making this cultural smorgasbord of a movie itself, but also textually rubbing your face in it in the actual film—that every human being is best served by letting them help themselves and gorge at the utter glut of all creativity ever made before they were born, and then letting them do literally whatever they want with it afterwards. At the end of the movie, Ghost Dog has given his copy of the Hagakure to this little girl, and you’re left with the question: is he sharing the violence in that book, or is he sharing the knowledge? Can you learn one without the other? Does Ghost Dog even get a say in how that plays out once he hands the book over? World’s Greatest Author Chuck Tingle knows the answer is no.

A work of art, placed in the world as a comfort to its creator, eventually (if it is blessed and lucky) strikes a chord with an audience that then looks to it for their comfort. And they can only express that love with more love. And the direction it flies and different shapes it births and births and births upon many births is just as unimaginable to the artist even one step removed from them as soon as they turn their back for even a second. Is Jim Jarmusch a fake try-hard because he likes black culture? Am I a racist hack because I write haikus before I fall asleep at night? Or did Jim Jarmusch and Ghost Dog soften me up for French New Wave Crime movies when I found those a couple years later? Is my life unimaginably more awesome because of Samurai Movies & The Spaghetti Westerns that Loved and Robbed Them? Are other people starving themselves because they think certain things “aren’t made for them”? The only thing you’re placing your art (or art appreciation) up against is emotional authenticity, either yours from day to day and work to work, or up against someone else’s work that they made. And more often than not, whenever you do that, you usually just end up looking each other in the face.

Ultimately, I believe that the final judgment of the work isn’t up to the work or even the work’s creator, it’s decided by us when we decide to take it into the future with us, in whatever shape or clothing we’ve decided to adorn it with for the case of the Chronological Bends to which we’re subjecting these beloved works that mean so much to us. Mutation is the sincerest form of flattery. We take them with us, and that’s the final priority and act of love and authenticity, just for me to shamelessly crib from Jarmusch himself:

Rule #5: Nothing is original. Steal from anywhere that resonates with inspiration or fuels your imagination. Devour old films, new films, music, books, paintings, photographs, poems, dreams, random conversations, architecture, bridges, street signs, trees, clouds, bodies of water, light and shadows. Select only things to steal from that speak directly to your soul. If you do this, your work (and theft) will be authentic. Authenticity is invaluable; originality is nonexistent. And don’t bother concealing your thievery—celebrate it if you feel like it. In any case, always remember what Jean-Luc Godard said: “It’s not where you take things from—it’s where you take them to.”

Edited by Olga Tchepikova-Treon