| Ed Dykhuizen |

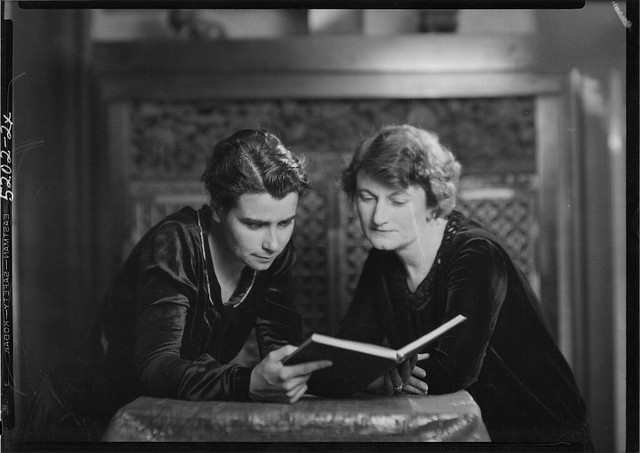

Image courtesy queeralternbern.ch

Merilly We Go to Hell plays on glorious 35mm at the Trylon Cinema from Friday, July 25th, through Sunday, July 27th. For tickets, showtimes, and other series information, visit trylon.org.

Female directors were commonplace, even at times dominant, in early film history. Alice Guy-Blaché directed more than 450 short films starting in 1896. Many scholars credit her with the first movie that had a narrative.

In these earliest years, small companies frequently sprung up to make movies. Someone would get a camera and rope in their family and friends to try out the exciting new medium. Filmmaking was a small-scale family business in which everyone pitched in any way they could. Western culture may have been very patriarchal, but there weren’t yet any professional norms about who was allowed to do what job in filmmaking.

Even as filmmaking professionalized in the early 1900s, women continued to hold leadership positions. Lois Weber was the primary American auteur of the 1910s, apart from D.W. Griffith. In 1915 she joined the major studio Universal and quickly became its highest-paid director. Weber worked with her own production unit and controlled every aspect of her films. Her controversial movies tackled contemporary social issues and brought in millions. Weber was the central figure of the so-called “Universal Women,” a major force in American filmmaking from 1916 to 1921.

The scrappy, booming motion picture industry of the 1910s was converted into a corporate studio system by the mid-1920s. Women were pushed out of positions of power and Hollywood became a strict boys’ club.

Behind the scenes, women were relegated to supporting positions as writers and editors. Such work is of course central to moviemaking, but producers and directors made the final decisions and got the credit for successes. Only people who worked with the female writers and editors knew the true importance they held in making hit movies.

One invaluable behind-the-scenes contributor of 1920s Hollywood was Dorothy Arzner. She got her start typing scripts for Paramount and quickly rose to the position of editor. After editing dozens of movies, she was pressed into service to direct some bullfighting scenes in the Rudolph Valentino vehicle Blood and Sand. Arzner did so skillfully, saving thousands of dollars by cutting in stock footage. Director James Cruze was impressed and took her under his wing. Arzner soon added screenwriting to her list of skills, which also expanded to all the technical aspects of filmmaking.

As Dorothy Arzner became more integral to Paramount, she knew she was ready to direct. The higher-ups refused to allow it. She accepted an offer to write and direct for Columbia, which was then a “poverty row” studio, of a significantly lower tier than Paramount.

When Arzner informed the people at Paramount that it was her last day, Production Head Ben Schulberg dropped everything to fuss and fume at her. She stood firm. He offered her a chance to direct eventually, maybe. She calmly demanded to start an A picture within two weeks. A few minutes later, he offered her a script called The Best Dressed Woman in Paris.1

Anyone who knew Dorothy Arzner, as Ben Schulberg certainly did, knew she had zero interest in the subject of this script, women’s fashions. Her outfits of pants, ties, and suit jackets stuck out among the women of the 1920s. Schulberg may have been setting her up to fail, or, more charitably, perhaps he didn’t think beyond “female director” translating to “movie about women’s fashions.”

Arzner met the challenge, turning the script into the hit 1927 film Fashions for Women. She went on to direct more than a dozen features. Her work was critical in the transition to sound films in the late 1920s. While filming Paramount’s first talkie, The Wild Party, Arzner discovered that Clara Bow couldn’t speak loudly enough in a convincing way to be recorded. Arzner solved the problem by attaching a microphone to a fishing pole, inventing the boom mic.

Arzner’s films are filled with strong female leads who fight against societal restrictions. These women almost always meet tragic ends, which sadly restore the status quo. Still, her films often contain triumphs of female self-actualization that were all too rare in the years before second-wave feminism. For instance, in Arzner’s film Christopher Strong, Katherine Hepburn plays an aviator who breaks records in a field dominated by men. The movie established Katherine Hepburn’s persona and made her a star. (Other legends who owe their careers to Dorothy Arzner include Lucille Ball and Ginger Rogers.)

Merrily We Go to Hell (1932) is not a typical Dorothy Arzner film in this sense. Its protagonist Joan Prentice, played by Sylvia Sydney, is not a bold nonconformist like Hepburn’s character in Christopher Strong. Joan does defy her wealthy family’s wishes and marries an alcoholic reporter played by Fredric March (who also got his start thanks to Dorothy Arzner). But when her new husband has an affair with an old flame, Joan doesn’t dump him outright. It’s hard to imagine that turn of events if Katherine Hepburn had played the role.

To be fair, Sylvia Sydney’s film persona was more one of a sunny, guileless, vulnerable charmer than anything like Hepburn’s brand of tough self-assuredness. I think Sydney could have pulled off a complete rejection of the husband, but she was also plausible in the decision her character makes instead.

Joan does not demand a divorce, but she does not roll over either. She resolves that they will have an open marriage and she will have an affair of her own. If you haven’t seen Merrily We Go to Hell, I won’t spoil who plays her date. Let’s just say he was certainly sexy enough to make for a realistic romantic rival to Fredric March.

Maybe Joan dumping her husband would have been more satisfying. But in the context of the early 1930s, initiating an open marriage was a bolder plot point. Men were smiled upon when they had sex outside of marriage, but women who did so were liable to be called “wanton” and worse. The so-called (and please forgive the outdated language) “Madonna/whore complex” predominated in the minds of American men: Women could either be faithful, supportive wives who did not exhibit any sexuality, or they could be sex workers whom men could use and discard without feeling empathy or guilt. In Merrily We Go to Hell, Joan plays the faithful wife to a tee until her husband cheats. Then she shows that she can be sexually interested in other people too.

Joan thus breaks the rules of the Madonna/whore complex and becomes a deeper, more interesting character. This and the portrayal of an open marriage caused controversy in 1932. Merrily We Go to Hell was one of many films in the so-called “Pre-Code Era” of 1930-1934 that involved women defying strict gender roles. Other examples include The Divorcee (1930), Possessed (1931), Queen Christina (1933), and Anne Vickers (1933). These are not cheeky films that aim to titillate straight men. They deliver messages about defiant women forging their own paths that were inspiring to female viewers of the 1930s who were trapped by systemic sexism.

These films were some of the primary drivers inciting social conservatives to demand tougher censorship of movies. One influential Catholic leader, Daniel Lord, summed up why this subgenre was so disturbing to the moral guardians of the 1930s:

“The stories are concerned with problems. They discuss morals, divorce, free love, unborn children, relationships outside of marriage, single and double standards, the relationship of sex to religion, marriage and its effects upon the freedom of women. These subjects are fundamentally dangerous.”2

In 1934, Daniel Lord and other Catholic leaders created the Catholic Legion of Decency, which compelled Hollywood to enforce the Production Code it had instituted in 1930. This slammed the door on movies that interrogated romantic and sexual relationships from female perspectives.

Dorothy Arzner kept turning out hits in the more restrictive environment. In 1943, she contracted pneumonia and convalesced for a year. When she finally recovered, she quit directing full-time. The rest of her life was spent on more sporadic projects, teaching filmmaking, and filming commercials. She lived far from Hollywood with her companion of more than 40 years, a female dancer and choreographer named Marion Morgan.

Image courtesy ebay.com

Arzner never discussed her sexuality openly, but she has become an icon for LGBTQ+ cinephiles. If you are interested, watch a short 1983 documentary by Katja Raganelli called Longing for Women: Dorothy Arzner. It’s a special feature on the Criterion Collection DVD of Merrily We Go to Hell and as I write this, you can see it on YouTube under the inaccurate title Dorothy Arzner: First Female Director.

Dorothy Arzner may not have been the first female film director, but she was one of the very few who were able to break through the tightly controlled boys’ club of Hollywood from the 1920s through the 1960s. Her films endure in part because of their strong, multifaceted, female protagonists that do not conform to stereotypes or male fantasies. Merrily We Go to Hell is a fun introduction to her fascinating body of work.

Footnotes

1 This and other information in this article come from “Interview with Dorothy Arzner,” written by Karyn Kay and Gerald Peary, which is available on the agnès films website at https://agnesfilms.com/interviews/interview-with-dorothy-arzner/.

2 Quoted in Mark A. Vieira, Sin in Soft Focus: Pre-Code Hollywood, New York: Harry N. Abrams, 1999, p. 55.

Edited by Olga Tchepikova-Treon