| Malcolm Cooke |

The 45-Minute Documentaries of Werner Herzog play at the Trylon Cinema from Friday, August 8th, through Sunday, August 10th. For tickets, showtimes, and other series information, visit trylon.org.

Werner Herzog has one thing to say to the proponents of Cinéma Vérité: “‘Happy New Year, losers.’”1 Herzog has always had beef with the idea of documentary as from the perspective of a fly on the wall, a genre of detached and objective reporting of facts. “That creed would make the CCTV cameras in banks the ultimate form of filmmaking,” he writes. Whether or not you think that such a description is a gross misrepresentation of the tenets of Cinéma Vérité, Herzog’s opposition to such concepts are a useful explanation for his own documentary style. As he says: “I don’t want to be a fly; I’d rather be a hornet.”

In 1999, Minneapolis’s own Walker Art Center ran a month-long tribute to the eccentric German filmmaker. During a Q&A session for the event, Herzog laid down his “Minnesota Declaration,” a tongue in cheek list of principles which elucidate his beliefs about the shallowness that comes from confusing “truth” and “facts” and puts forth his own alternative idea of “Ecstatic Truth.”2 To him, Cinéma Vérité produces a “superficial truth, the truth of accountants,” but cinema can effect a “deeper strata of truth” that comes through “fabrication and imagination and stylization.”

This might be why Herzog insists “there is no meaningful difference between his features and his documentaries.”3 In both situations he is a storyteller, trying to get at some deeper poetic truth. Although his subjects may be real in some films and fictional in others, he heightens and stylizes reality to dispense lessons borne of his famed gloomy, teutonic, and poetic worldview.

Newly restored, five short documentaries all produced for the German state broadcasting corporation Süddeutscher Rundfunk show Herzog’s philosophy of Ecstatic Truth in action. With eclectic subject matter ranging from a volcanic eruption in Guadalupe to the frenetic form of speech used by American cattle auctioneers, each story is clearly borne of some deep fascination Herzog has with a person or phenomenon. Whereas other documentarians might try to investigate and define the inner workings of an institution or create a journalistic chronicling of an event, Herzog’s docs meander above, grasping at some deeper ironic and poetic issue at the core of each film.

For example, the film about cattle auctioneers How Much Wood Could a Woodchuck Chuck if a Woodchuck Could Chuck Wood? (1976) deals with Herzog’s fascination with language and its limits. Structured around the World Livestock Auctioneer Championship of 1976, a large portion of the runtime focuses purely on the frenetic performances each auctioneer gives. Herzog was so fascinated with this form of language he recast one of the champion auctioneers in his film Stroszek (1977) a year later for a scene in which the eponymous lead, an immigrant from Germany, experiences the dilapidated corpse of the American Dream as his final possessions auctioned off. Herzog even wanted to make a version of Hamlet with all parts played by champion livestock auctioneers (the total runtime, he estimates, would clock in at under 14 minutes).4 To Herzog the language becomes, “singsong, a cascade of madness impossible to intensify further,” a sort of insane raving he views as “the last form of poetry or at least the last language of capitalism.” The unique dialect that seems to be almost coming apart at the seams. To him it represents a kind of disintegration of meaning that comes with the alienation of capitalism. As the auctioneer tells a German immigrant pleading with him after he has lost all he owns: “I’m sorry sir, I cannot understand you.”

Herzog has a knack for finding people who seem like they might be characters in one of his fiction films. God’s Angry Man (1981) explores the controversial televangelist Dr. Gene Scott, known for his countless lawsuits and fracas with the FCC over tax income. The film does have its moments of scathing condemnation. “Do you understand that God’s work hangs on 600 miserable dollars?” Scott screams in one scene where his call in donations aren’t quite meeting the several hundred thousand dollar goal for the night. But extensive interviews with Scott probe his psyche and continually leave the audience questioning whether Scott is genuine in his own beliefs. As Scott frankly discusses his own infertility and strong desire to have a family, he is imbued with enough pathos to make him seem like he would fit in well with Klaus Kinski’s monomaniacal Aguirre as a classically tragic Herzog character.

In La Soufrière (1977) Herzog explores an abandoned city underneath a volcano in the Caribbean island of Guadalupe, chock full of biblically apocalyptic imagery and quotes such as “the sea was full of dead snakes.” They find a man who has refused to leave, ask him why, and are met with the response “I am here because it is God’s will. I am waiting for my death… where should I go? Death waits forever, it is eternal.” A more darkly poetic Herzogian scenario could not have been thought up by the man himself.

This is where once again Herzog’s Ecstatic Truth unifies the feelings of his fiction and non-fiction film. Whether he has written a script or simply found some ironic phenomena in the real world, he stylizes his presentation to express the absurd, poetic, and tragic elements of our world. In The Dark Glow of the Mountains (1985) he follows legendary South Tyrolean mountain climber Reinhold Messner along with his compatriot Hans Kammerlander as they cross two eight thousand meter high peaks in the Karakoram mountain range in Pakistan. Like many of Herzog’s documentaries it could superficially almost be a national geographic production. But instead of focusing on the geography of the area or the technical skill involved in climbing such a peak, he narrows in on the subject much more interesting to him: Messner himself. Asking probing and philosophical questions of the man (“Do you have a death wish?” “Do you feel as though your brother died in your place”), he gets back equally cryptic and revealing answers about what drives Messner to pursue such a dangerous task, as well as some genuinely affecting emotional eruptions. Herzog is perhaps so good at finding and prying open these strange and fascinating characters because he is one of them himself. When Messner describes a surreal desire he has to give up mountain climbing, purchase some pack animals, and keep walking across the earth until it comes to an end, Herzog without a beat replies, “That’s strange because I have exactly the same fantasy.”

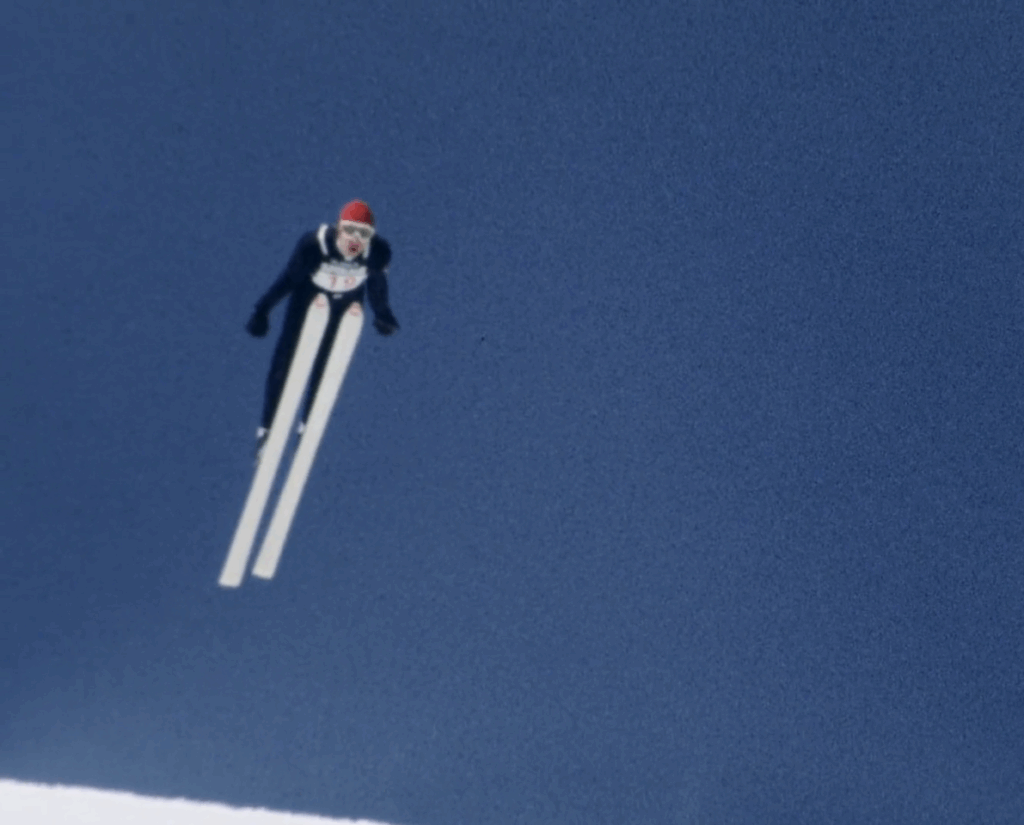

The last but perhaps most ethereal and intriguing of these characters is Walter Steiner, the subject of the film The Great Ecstasy of Woodcarver Steiner (1974). Steiner, a slender and graceful ski jumper, is introduced skillfully performing his full-time day job as a carpenter. While the film does on the surface level follow some semblance of a plot (the drama of Steiner dealing with injury and overcoming record jump lengths at an event in Yugoslavia) the true core of the film—the Ecstatic Truth at which Herzog grasps—comes with the epic slow motion shots we are quickly treated to of Steiner flying through the air to the dulcet sounds of frequent Herzog collaborator Popol Vuh. There is something otherworldly about the calm with which Steiner composes himself as he repeatedly overcomes world record after world record with ease. In his exploration of the freedom and beauty in Steiner’s graceful ski flying (not ski jumping) we see the true encapsulation of Herzog’s goal of avoiding stuffy objectivity in favor of powerful poetry and metaphor, even in a documentary film. Perhaps the single moment that most clearly signifies this is a story Steiner tells at the end of the film. When he was about 10 or so, he found a young raven which he raised himself, weaning it on food he would give to it after he got home from school. Both the bird and Steiner were loners and the bird would fly alongside him and perch on his shoulder as he rode his bike. But one day, as the bird was molting, a group of other ravens attacked it, damaging its wings so it could no longer fly. Steiner, unable to take the pain of the raven any longer, fetched his father’s rifle and put it out of its misery. Herzog himself gives the meaning of the parable: “Now that his raven no longer flew, he, Steiner, flew in its stead.”5

References:

1 Michael Hoffman, translator “Every Man for Himself and God Against All: A Memoir.” by Werner Herzog, New York, Penguin Press, 2023, pp 285.

2 Ebert, Roger, “Herzog’s Minnesota Declaration: Defining ‘ecstatic truth’” RogerEbert.com December 19, 2012, https://www.rogerebert.com/roger-ebert/herzogs-minnesota-declaration-defining-ecstatic-truth

3 Zalewiski, Daniel, “The Ecstatic Truth” The New Yorker, April 16, 2006, https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2006/04/24/the-ecstatic-truth

4 Michael Hoffman, translator “Every Man for Himself and God Against All: A Memoir.” by Werner Herzog, New York, Penguin Press, 2023, pp 265.

5 Michael Hoffman, translator “Every Man for Himself and God Against All: A Memoir.” by Werner Herzog, New York, Penguin Press, 2023, pp 42.

Edited by Olga Tchepikova-Treon

Pingback: MN Shortlist Aug. 8-15: Sheila E., theater of vice - Maple Grove Local News