| MH Rowe |

Casablanca plays on glorious 35mm at the Trylon Cinema from Sunday, August 17th, through Tuesday, August 19th. For tickets, showtimes, and other series information, visit trylon.org.

Things are not quite as you remember in Casablanca. Consider before anything else the film’s hellish yet also somewhat corny setting. Here we have the city of Casablanca on the coast of Morrocco only days before Pearl Harbor, December 1941. None of the film’s characters know the fateful Japanese attack is coming, of course, but the film itself seems raise its eyebrows meaningfully when the date is mentioned. Though ruled by a colonial administration loyal to the Vichy government in France, Casablanca enjoys an ambiguous freedom. The city’s French authorities appear insulated to a certain extent from more official support for Nazi interests carried out by the Vichy regime on the European mainland. This Atlantic-Mediterranean metropolis has thus become a waystation and abyss, a combination of casino and prison. If you have the means, you can obtain a visa and a flight to Portugal, specifically to Lisbon, that “great embarkation point,” as the film’s introduction has it, as if to describe the spaceport for the last ship leaving a dying earth.

And so the film Casablanca transfigures the city Casablanca. Here it looks less like a strategic point on a wartime map and more like Purgatory. Only this Purgatory sits between the Nazi camp Europe is becoming and the shrinking exit to an American or British frontier—a wild West of hope—that might serve as a refuge or itself be overrun. The film’s setting is therefore not terribly real for all its terrible reality. More than real, it is mythic, exotic, and half dream.

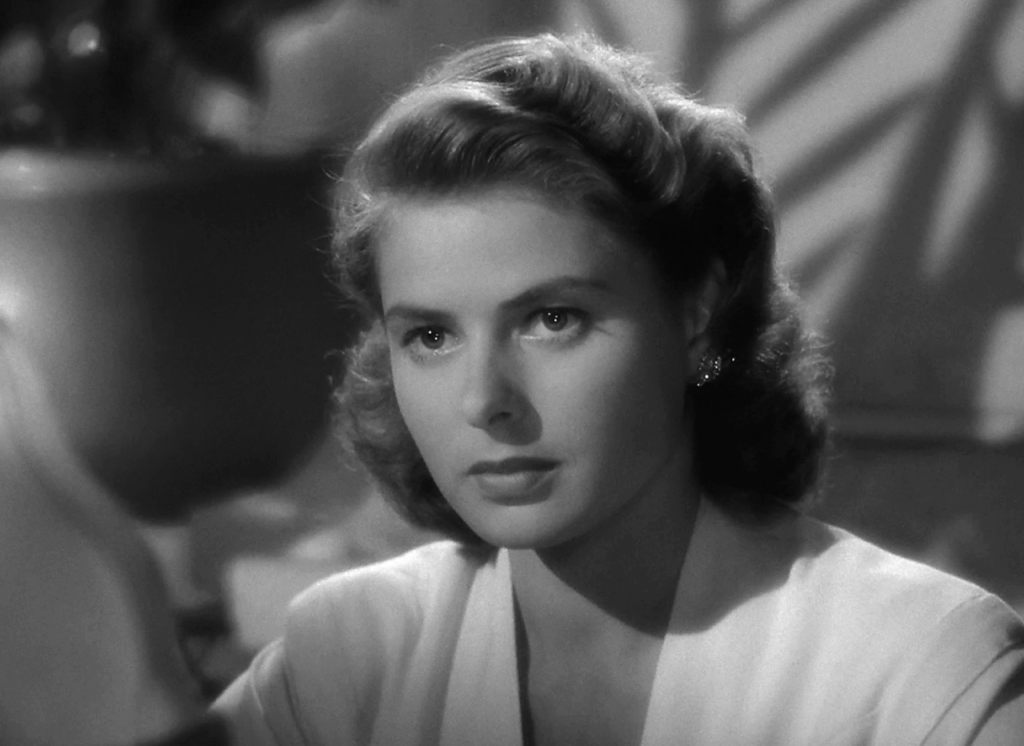

In this twilight Casablanca we find Humphrey Bogart, famously (redundantly), as Rick Blaine, a man strung out between worlds. Once paid to traffic guns in Ethiopia and to fight the fascists in Spain, Rick now works a job often held open for disaffected leftist soldiers of fortune: nightclub owner. In what strikes me as a particularly perfect bit of purgatory, Rick’s pianist Sam (Dooley Wilson) at first refuses to play a song Ilsa Lund (Ingrid Bergman, famously and redundantly) requests—“some of the old songs,” she says, like she’s putting on an Instagram filter—and then relents because it’s a movie and Sam is paid to sing, Rick is supposed to be sad, and Ilsa is the reason why. As the poet said, what fools these mortals be. Their torments are so great and small, not even pianos are safe. That’s the paradox of popular song anyway, that it can be the most intimate personal expression.

Is there an English-language film more enduringly famous than Casablanca and its iconic song, the latter of which I find, frankly, a total irritation, cloying and forced? Be that as it may, Rick and Ilsa stand at the foundation of twentieth-century cinematic romance. (Really, Casablanca works so well because it hews close to its soul as romance rather than its credentials as a wartime drama.) Together in Paris during a time when she thought her husband Victor dead, Ilsa left her new lover Rick on the day of their planned flight from France. This scheduled elopement of sorts coincided with the arrival of the Nazis. Only upon her own arrival a year later, in his Casablanca nightclub, does Rick begin to learn why he was left drenched in all that melodramatic rain, alone at the train station without his girl. Except there stood Sam, telling him it’s time to go. Ilsa’s husband, the superhumanly upstanding resistance leader Victor Laszlo (Paul Henreid), was not only alive and in need of his wife but now, in Casablanca, needs as well a visa Rick has in his possession. Victor and Ilsa must get to Lisbon and then to America. Rick has of course hidden the visa in the piano. Sometimes you can trust the fucking thing with your secrets, sometimes not.

When production of Casablanca began, not even the filmmakers had made up their mind whether Ilsa would be with Rick or Laszlo by the end. The script was incomplete. They did have, however, their shifting and shifty theme, as the movie traffics not simply in visas but women. Utmost here rises the charming and reprehensible Captain Louis Renault (Claude Reins). No viler character could be more winningly performed. You almost but can’t quite forget that Renault, as the city’s executive French police officer, has a career trading travel papers for sex. He seems, for his part, to view himself as but a simple rake, referring to his prostituting demands as “little romances” when Rick intervenes and ruins one of them.

That Renault coerces these women, whatever he tells himself, couldn’t be clearer than in a scene not nearly as celebrated as other of the film’s iconic segments, although it’s quite moving. At the club, a woman named Annina (Joy Page) sits with Rick. She explains that she and her husband are Bulgarian refugees, in desperate need of papers. They have no money, so Annina wants Rick to tell her that Captain Renault will keep his word and provide them with visas if she does this “bad thing” and sleeps with him in exchange for passage out of Casablanca. She also implores Rick to reassure her that “as a man” he could absolve her of this sexual betrayal, since it really isn’t, she hopes, treacherous at all but instead a heroic act of sacrifice, an act of love. That she will forfeit some part of her dignity sleeping with Renault becomes obvious when Rick darkly assures her that Renault “always has” kept his word in such circumstances. Page’s quiet, faltering “Oh” as she realizes the depth of the captain’s roster of sexual conquests is enough to break any sentimental heart. It certainly breaks Rick’s. He quietly arranges for Annina’s husband to win at roulette.

This crucial scene sets Rick on a path to help Ilsa and Laszlo, even if he proceeds in a byzantine way he’s obliged to follow as the protagonist of a suspenseful film. What Rick realizes nevertheless are the punishing ironies of the world in which he lives. No matter that such compromises are familiar in this sort of tale. For what looks superficially like feminine betrayal may instead be a foundational act rather than a destructive one. A portion of the world’s pain taken as communion with a Nazi reality of borders and desperate circumstance.

Annina told Rick too, with great tenderness, about the naivete of her husband. She surmises that she is really “so much older than he is.” Rick takes this logic for his own when he considers Ilsa, who even invites him to do the thinking for both of them. The film seems to insist on this deference. Ilsa married Laszlo when she was quite young because he initiated her into a righteous and brave world, a world full of the mythic resonances of resistance, which seems to be the ultimate romance, giving meaning to past, present, and future alike. A grand act of the imagination. Rick’s tutelage or power—and the film makes Ilsa out to be, unlike Page, the junior partner in her romances—was more strictly erotic. Ilsa’s attachment to Rick suggests an entirely different, irreproducible manner of feeling and thought. “We’ll always have Paris,” as he tells her, doesn’t refer to Paris at all but the mysteries of what they call chemistry, though really they should say alchemy, since that’s what we mean. It resists all formula, all certainty. Laszlo stands for some ultimate meaning, Rick for an alchemical allure.

In the end, Rick takes ironic pleasure in sending Ilsa off with Laszlo, whose righteousness has more or less seductively rubbed off on him. Rick believes or tells himself he believes in the death of his and Ilsa’s love—“maybe not today, maybe not tomorrow, but soon and for the rest of your life.” If it seems a little self-aggrandizing, a show of male pride, Bogart sells it with conviction. The ending of the film discloses anyway the other romance toward which Rick has been returning step by step over the course of Casablanca, namely the war. Rick and Renault’s final murder of the Nazi Major Strasser (Conrad Veidt) and their turn to resistance fighting—“I think this is the beginning of a beautiful friendship”—seems deliciously preposterous. But they commit themselves in the name of mastering their own fate. As Ilsa was seduced by Laszlo’s grace, mild mercy, and political commitment, so Rick and Renault are drawn into the good fight by Laszlo’s example. This constitutes the real love story of the film. An American falls in love with the war at last, in that unreal city called Casablanca.

Edited by Olga Tchepikova-Treon