| Wil McMillen |

Requiem for a Heavyweight plays on glorious 35mm at the Trylon Cinema from Friday, August 29th, through Sunday, August 31st. For tickets, showtimes, and other series information, visit trylon.org.

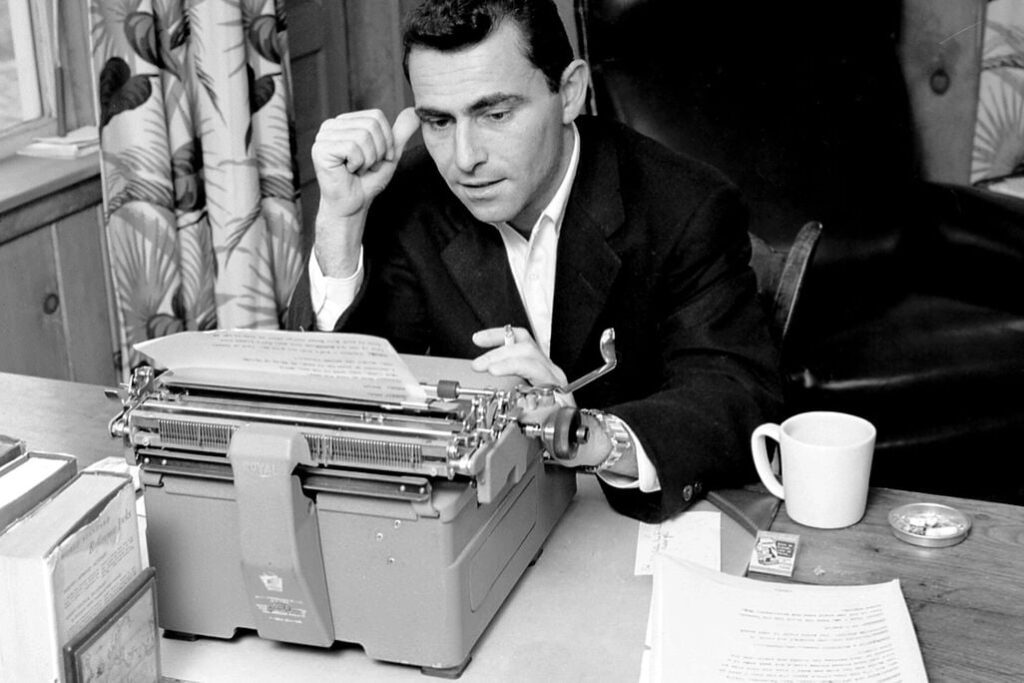

Portrait of a nervous man in the midst of a crisis. He’s sitting with his wife, having dinner at a Howard Johnson’s. The air is heavy with what he needs to tell her. Earlier that day he quit his job at the local radio station after being tasked with writing a show based on a new medicine. It’s his final straw. Rod Serling, age 27, is presenting the leap of faith into freelance scriptwriting to his pregnant wife. He’s toiled in the machine for six years. If it doesn’t happen now, it won’t happen. She smiles, takes his hand, and accepts this change of events.

Neither of them denied it was a risky decision. Television was in its infancy, even as American households were buying up televisions faster than stores could keep them in stock. Television drama was only just beginning to mature into an art form. Serling was in the right place at the right time. Paddy Chayefsky’s Marty made the first splash, forming the tidal wave of what’s called the Golden Era Of Television. This was followed the next year by Reginald Rose’s 12 Angry Men. Serling himself had written more than 70 scripts for radio and television by the time he wrote Patterns in 1955.

Initially written for CBS Studio One, which passed on it, Patterns was broadcast on the Kraft Television Theater on Wednesday, January 12, 1955. It was the day Rod Serling’s life changed. The play caused such a sensation it was presented again a month later, an unprecedented feat in a time of live television drama. Marty had won the Oscar for best picture earlier in 1955, so a film version of Patterns was rushed into production, with Serling adapting his own script.

Serling had seen that culture was changing in the 1950s. This was the explosion of Wall Street. The war was over; sacrifice was passé. There was money to be spent and things to be bought. Between 1950 and 1960, American buying power grew by 37%. The American ideal of the “rugged individual” was a thing of the past. Now, here was William H. Whyte’s “Organization Man,” a person who let go of their individuality in the pursuit of middle management. Standing out amongst your peers was frowned upon. Conform, and you too could one day move up in the company.

Serling realized this kind of system rewarded the worst people. It removed the soul from a corporation and put profits over people. The 40-story building where most of Patterns takes place is Walter Ramsey’s castle and once the day is started, the king has arrived, the drawbridge is lifted, and your life is the business.

And there is no escaping Ramsey’s castle. Not only does Ramsey rule his building, but he makes himself at home in new employee Fred Staples’s house, during a dinner party, looking over a report that Staples has written with veteran employee Bill Briggs. Ramsey is both organizer and antagonist. He is not looking for outside thoughts or opinions. He wants complete and total affirmation from his team. Briggs, on the other hand, seems to be the only principled man on the board who is willing to express and insist on his ideals. Ramsey doesn’t want to hear about principles. He has no use for ideals. He wants no reminder of the workers he will put on the unemployment line. So he insists on removing Briggs’s name from the report, in an attempt to make him finally quit.

In the climactic boardroom fight, Briggs is shocked to learn his name has been removed from the report. Briggs is justified in standing up for himself, but halfway through arguing with Ramsey, Briggs breaks. After forty years of this, he’s finally wounded enough that he stops fighting back. It’s now Staples’s turn to take up the idealism reins and he angrily argues with Ramsey that Briggs deserves to have his name on the proposal. Staples begs Briggs to fight back, but it’s too late. Briggs is dead before he’s deceased. He says under his breath that it was a clerical error, walks quietly into the hallway without anyone following him to check on him, and dies outside his office. Ramsey finally has an empty office to fill, which is what he wanted all along, and Staples is the guy to do it.

According to the introduction to the kinescope of the television play, Serling originally wrote a different ending to Patterns. In the first version, Staples walked into Ramsey’s office not only to quit, but also moved back to Ohio as a hero with his morals intact. While it’s explained that it was done for aesthetic reasons, the fact that this change occurred between the rejection by CBS Studio One and the pickup by Kraft seems to indicate that the sponsor of CBS Studio One did not like having the brutal antagonist of Patterns be a ruthless CEO. Serling rewrote the ending with a darker, less hopeful, but ultimately better and more realistic ending. Ramsey, knowing what Staples needs to hear to make him stay, doubles Staples’s salary and stock options. He tells Staples he can have whatever he wants as an expense account. Staples is the only person that will challenge Ramsey, and Ramsey says that’s what he needs on his team. And Staples falls into his trap and accepts the offer. We can infer this is almost the same conversation he had with Bill Briggs many times over 40 years. Ramsey has already run this scene. He knows his lines in this drama that will get him what he wants.

And Ramsey will always win. He’s the king after all.

Serling saw the cost of living in a system like this. By this point he had worked in television for six years, and had felt the battering ram of working with corporations. In a talk he gave at UCLA in 1971, he remarked “However moving and however probing and incisive the drama, a show cannot retain any consistent thread of legitimacy when, after 12 or 13 minutes out come 12 dancing rabbits with toilet paper. It puts the creator, particularly the writer, in a tough emotional bind, though…How do you predatorily bite the hand that feeds you consistently?” The cost of a system built like this one is not just business, it’s personal. What morals are you willing to sell in order to see your project, your script, your proposal come to fruition? Briggs literally dies at the end of the film due to the pressure put on him by the corporation.

Serling’s Patterns captures the moment in history when the corporation became the defining organizing influence in everyone’s life, and in its chilling final moments, it asks the question “What are you willing to give up to succeed?” More times than not, the answer is “everything.” Staples leaves the office quietly with his wife having just accepted his fate. While we aren’t told what the future holds for him, we can guess. And that future isn’t very bright.

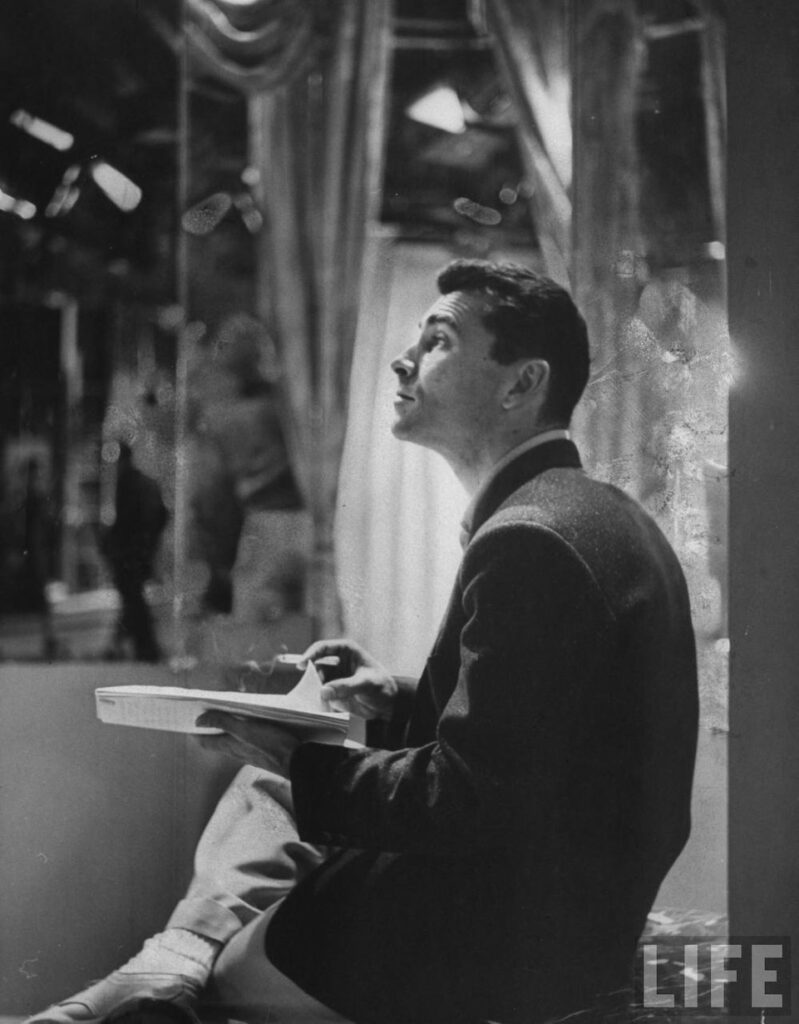

Serling’s future, however, was suddenly shining like the sun. Thinking it was just another one of his plays, Serling had gone out of town with his family on the night of the premiere. He was shocked when he came home to find his phone ringing off the hook.

And it never stopped ringing. One can imagine Serling feeling like Fred Staples, standing on the street, excitement in his stomach, the future bright. It didn’t take long before the cold reality of what had just happened became clear to him.

At the 1956 Emmys, Serling won the first of his many awards for writing. When his name was announced as winner for the Best Original Teleplay for Patterns, he leaped up, happy to be recognized by his peers. Dashing up to the stage to accept his award, he arrived alone, the blinding glare of the lights in his face. Nobody was there to greet him. After several uncomfortable moments, a gentleman came in holding the Emmy. He shoved it into Serling’s stomach “like a quarterback handing off to a right half,” pointed to the stairs, and motioned for Serling to leave the stage. “Later that evening,” Serling writes in the introduction to his script, “as I carried the Emmy through the lobby of the Waldorf-Astoria…it appeared just a little bit tarnished…There is something just a little bit straining to the stomach to know that the writer comes in, in the last column, in the last segment, and receives the award in circumstances that make it appear to be almost an afterthought.”

Serling knew that writing on the scale and impact of Patterns wasn’t something that came easy. As he writes in his notes on the script, “I now had to fight for myself or at least something I’d done…There had been other things before and there would be other things to follow. As it turned out, it took a long time to prove. One of the plays turned out to be one that, for the moment anyway, pushed back this specter of the “flash in the pan.” This was Requiem for a Heavyweight. In many ways it seemed to catch the public imagination just as Patterns had. Its reviews were fabulously good. And now in the columns, I’m ‘Rod Serling, who wrote Patterns and Requiem for a Heavyweight.”

What is not mentioned in that quote is the year-long battle he fought to bring his teleplay Noon On Doomsday to the screen, based on the killing of Emmitt Till. Serling already knew he couldn’t present the complete racial issue he wanted to face without being rejected, so he initially created the victim as an old Jewish man in a New England town. No connection to Emmitt Till, to racial violence, to the South. But he made the mistake of mentioning the plot to a reporter. The news that the writer of Patterns was set to tackle the Till case created an instant firestorm.

Recalling pre-production procedures, Serling writes, “The script was gone over with a fine-toothed comb by thirty different people, and I attended at least two meetings a day for over a week, taking down notes as to what had to be changed. My victim…was to be called an unnamed foreigner, and even this was a concession to me, since the agency felt that there should not really be a suggestion of a minority at all; this was too close to the Till case. It was a Pier 6 brawl to stop this alteration of character. The script was then dissected and combed so that every word of dialogue that might remotely be ‘Southern’ in context could be deleted or altered…this was to be a total surrender, and there would be no concessions made even to logic.”

Writing is a constant battle to connect. For the writer, you pull from the bottom of your soul the things you feel. The writer wants to entertain, to express themselves, to say the things that aren’t easy to say. The writer extracts the very bottom of themselves, more than most people do. It’s no wonder writers speak of bodily fluids when they talk about the act of writing. They “opened a vein onto the page,” or they “vomited” the words out. For the writer, the act of writing is just as violent as a boxing match. In many ways, it’s described as a trauma to the body. And when you have to constantly battle the forces of the people holding the purse-strings to your art, you start figuring out ways to smuggle your message out in ways they may not notice, so you don’t have to fight. You entertain while still doing what you were born to do. And this is the lesson Serling had learned the hard way with Noon On Doomsday.

In response, Serling wrote Requiem For A Heavyweight. One of his personal favorite scripts, Serling puts us on that empty Emmy stage with him. He puts us in the corporate boardroom as his script is torn apart in front of him. He stands us beside him as he fights for every single word he has very intentionally put on the page. He pours his soul into the broken body of an amateur boxer (which Serling had been) and subconsciously makes us feel the beating, bruising, bloody, beautiful wreck of being a writer. Requiem For A Heavyweight is the story of Mountain Rivera (Anthony Quinn), who is forced to confront his future when he’s told that another boxing match could leave him completely blind. As his corrupt manager, Maish (Jackie Gleason) continues to try to exploit Mountain, so he can pay off his gambling debts, Mountain struggles to find meaning beyond the boxing ring. Serling the writer is fighting back against those that would exploit and take advantage of him, and by the end of the film version, he’s not sure if he’s going to win.

In a 1959 interview with Mike Wallace, Serling says “I don’t want to fight anymore. I don’t want to have to battle sponsors and agencies. I don’t want to have to push for something that I want and have to settle for second best. I don’t want to have to compromise all the time, which in essence is what a television writer does if he wants to put on controversial themes.” You can hear the echoes of Mountain Rivera, in the final scenes of Requiem for a Heavyweight, tearful, wearing his Native American outfit while waiting for his first wrestling match, begging Maish to not make him put on the costume and wrestle.

I bring this up because the ending of the film version of Requiem for a Heavyweight is wildly different from the ending of the teleplay it is based on, both written by Serling, but having been written at different points in his career. It’s striking that he decided to change his original, somewhat heartwarming ending of the teleplay into the dive into a nightmare the film version presents. In the original teleplay, once Mountain learns that Maish bet against him in his last fight, Mountain leaves Maish and heads for Tennessee. Maish begins working with the young boxer (introduced to him and thrown out of the locker room in the film version), and Mountain meets a child at the train station where he’s leaving town and decides to work with the kids at the camp. Maish has given into the corrupt world of boxing, but Mountain has escaped with his dignity intact.

The film version, however, ends with the moneymen coming to collect when Mountain refuses to go into the ring. There is a fistfight and Maish’s life is threatened. In an effort to save Maish, Mountain gives up the last of his dignity, puts the costume back on, and enters the wrestling ring as the crowd boos him.

Although it was originally broadcast in 1956, the film version of Requiem For A Heavyweight was not made until 1962, nearly three years into the run of the series that would make Rod Serling, truly, a household name.

It’s impossible to talk about Rod Serling without bringing up The Twilight Zone. It’s a towering achievement and one of the greatest television shows ever made. But Serling had realized that in order to bring up the things he actually wanted to talk about, he had to compromise and disguise his messages behind the façade of science fiction and horror. He could still be an artist, and still be in control, and still write scripts that are so artistic they’re studied in schools, but he had to play the part of ringmaster of a genre that at the time was disreputable in order to regain that control.

Knowing all this, it’s hard to watch this final scene of Requiem For A Heavyweight and not think about how Serling, by the time he wrote the screenplay for the film version of Requiem For A Heavyweight, had compromised his hard hitting scripts and instead had to cover their messages in the skin of science fiction. Just like Mountain, he was doing the dance. He was wearing the costume. He was still in the ring, he had control and was making the decisions, but I wonder about this ending and Serling’s true feelings about The Twilight Zone. Twice in his career he had changed his original happy and heroic endings into dark and troubling conclusions. I don’t mean any disrespect to The Twilight Zone, (it’s my all-time favorite television show), and I certainly hope this reading of Requiem For A Heavyweight doesn’t ruin your experience with that series. But I have to consider how dark the film dives. The original teleplay and the film are so different, I have to wonder exactly where Serling’s head was at after writing 63 episodes of the series by himself at this point. He would ultimately write 93 of the 156 episodes of The Twilight Zone in the five years it was on the air. That blizzard of writing is truly astonishing.

Serling never came to terms with the compromises he had to make in order to get his stories broadcast, even with the control he had on The Twilight Zone. In nearly every interview Serling gives, the subject of battling corporate sponsors comes up. It’s not hard to see the parallel with Serling’s own life. This change in endings between the teleplay and the film is the difference between a fighter just beginning his career and the veteran who has taken so many punches, there’s not much fight left in him. The film’s ending in the wrestling ring is a vision of Mountain’s hell. He’s trapped, entertaining the crowd by doing the only thing he believes he has talent at, in the only way he knows how.

After the triumph of The Twilight Zone, Serling created a Western that lasted one season (The Loner), and wrote a few movies, including Seven Days In May and Planet Of The Apes. By the time he got back in the ring, put on the costume, and became the host of Night Gallery in 1969, Serling was bruised and battered from a lifetime of fighting for his voice to be heard. Like the film version of Mountain, he had been diluted, censored, and watered down into the shape of what someone else wanted him to be. By 1975, Rod Serling’s heart gave out.

So, picture if you will, a man who once wrote about an idealist who found out climbing the corporate ladder only leads you to the gallows. A man who once wrote about a fighter who gave everything he had in the ring, only to be destroyed by the business outside of it. A man whose arena was the television screen, the opponent his sponsors, and the final bell rung at the age of 50. Rod Serling, who gave everything he had, discovered in the end he could only make the art he wanted by entering The Twilight Zone.

Edited by Olga Tchepikova-Treon