| J.R. Jones |

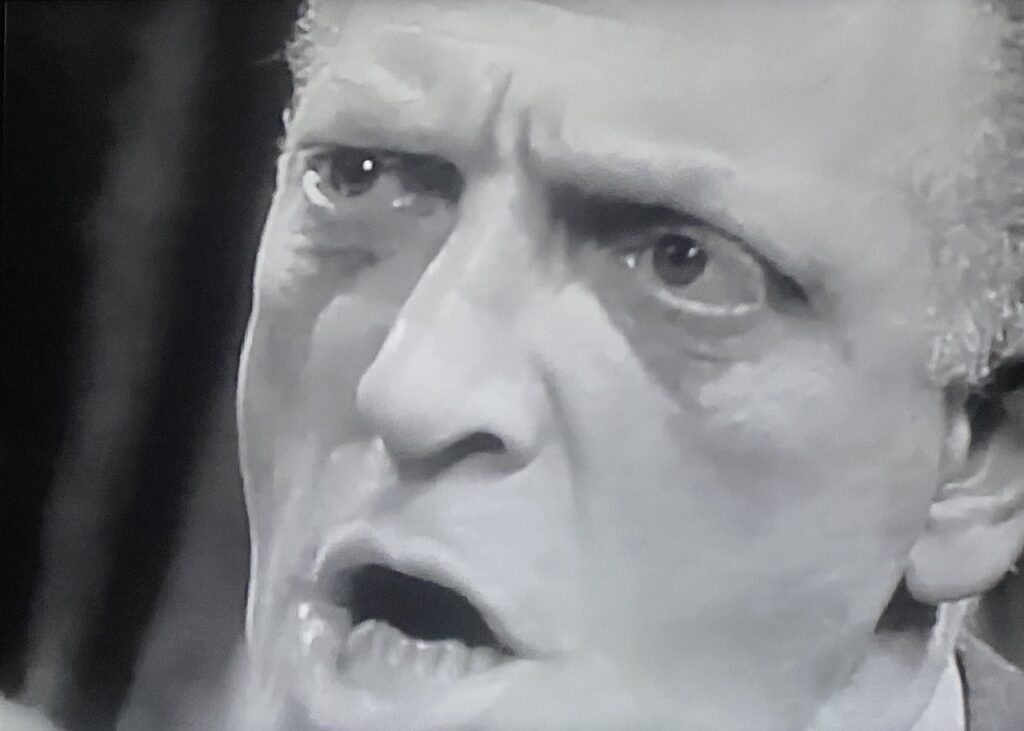

Andy Sloan (Ed Begley), Mr. Ramsie (Everett Sloane), and Fred Staples (Richard Kiley) clash during an executive meeting in Rod Serling’s 1955 teleplay Patterns.

Patterns plays at the Trylon Cinema from Friday, August 29th, through Sunday, August 31st. For tickets, showtimes, and other series information, visit trylon.org.

This review contains spoilers.

In our modern media landscape, where TV and the movies are slowly dissolving into a giant video stream, we might not recall that 70 years ago these two media were starkly distinguished. Movies were prestigious, a serious art form, and television was derided as “the idiot box.” Rod Serling is best remembered now as creator, producer, and frequent writer of the anthology TV series The Twilight Zone, but he may have left his greatest impact on the medium four years earlier—on January 12, 1955, when his one-hour teleplay Patterns debuted live on ABC’s Kraft Television Theatre. The next morning, Patterns (which you can watch in its entirety here) was the talk of the nation, hailed as proof that TV could deliver acute social drama on par with the cinema.

The broadcast made Serling a star overnight in a business that was then anchored in New York City, and whose numerous dramatic anthology series, performed live before the advent of videotape, followed more in the tradition of the New York stage than the movies. A highly opinionated man, Serling became a harsh public critic of television but also one of its most loyal defenders. “I like movies as a change of pace, but TV is much more intimate,” he told Newsweek at the end of that year. “You’re looking at people close up, physically and psychologically.”1 The screen version of Patterns, released two months later, only proves Serling’s point: it scrupulously preserves the text of the teleplay, but gone are the giant faces, swift pacing, and opening-night electricity that made the original performance so gripping.

As a boy in Binghamton, N.Y., Serling grew up listening to radio dramas, which shaped his narrative sense; after serving as a paratrooper in World War II, he earned a degree at Antioch College in Ohio and wrote scripts for local radio before hiring on as a TV writer at WLW in Cincinnati. His first anthology series, The Storm, was shot on a set so small that Serling had to learn how to tell a story in close-ups. He also got a close-up look at how the business world operates. “There was a guy called Jack Z who worked at WLW, who actually died of a heart attack because of the pressure,” remembered one of Serling’s co-workers. “And there was another guy who helped put the screws to him by the name of Fred G. All of them wanted Z out. The trick they used was to write memos that they had in corporate meetings, put his name on the list of those to receive the memo—but never actually give him a copy.”2

This experience became the inspiration for Patterns, which Serling wrote after quitting his job at WLW to become a freelance scriptwriter for network shows. Though not yet a New Yorker, he transplanted the action to Manhattan, where young Fred Staples arrives for his first day of employment at the high-powered Ramsie and Company. An industrial relations man, Staples has been recruited from Cincinnati by the hard-charging president, Walter Ramsie, to support the graying Andy Sloan, a vice president and, with Ramsie’s father, a founder of the company. Staples and Sloan grow friendly, but eventually Staples figures out that he’s been brought in to nudge Sloan into retirement. The situation comes to a head after they collaborate on a big report and Ramsie, hoping to humiliate Sloan in an executive meeting, orders his name struck from the title page before the report is distributed.

Ramsie attacks in the live teleplay, broadcast January 12, 1955.

The opening of Patterns shows how sophisticated live TV drama had grown in the seven years since television became a commercial medium. Director Fielder Cook opens with a filmed shot of a Manhattan skyscraper, its clock marking 8 AM; cuts to a long shot of Miss Lanier (Joanna Roos), Ramsie’s secretary, boarding an elevator in the lobby; pans past the elevators to a framed directory for Ramsie and Company, following the names from bottom to top; picks up a wall clock in the deserted telephone operators’ station, follows the coiling connection wires and sweeps across the operators’ desk; and cuts to a grandfather clock, this one in the lobby of Ramsie and Company, where he meets up again with Miss Lanier—all in 50 seconds. Over the next hour, Cook cuts back and forth between seven sets as more than 20 actors play scenes in real time. The sense of a pressurized work environment is palpable because, for the actors and crew, it was one.

Despite the elaborate staging, Patterns is most powerful for its close-ups, which can hark back to the silent cinema in their intensity. In 1955 the average TV screen was about one foot wide, so the medium was inhospitable to long shots with too much detail. Yet Serling had mastered the medium back in Ohio: his story plays out across the faces of his characters. Richard Kiley (as Fred Staples), Ed Begley (as Andy Sloan) and Everett Sloane (as Walter Ramsie) all give fine performances, and frequent close-ups of the secretarial staff (among them Elizabeth Montgomery, later of Bewitched) not only democratize the action, allowing these minor characters to pass silent judgment on their bosses, but efficiently communicate the back-biting office culture that’s being weaponized against Sloan.

On a movie screen, characters can still seem far away, but on a TV screen they can be too close for comfort. Witness the climactic scene of Patterns, after Sloan has died and a guilt-ridden Staples marches into Ramsie’s office to resign. His speech condemning Ramsie for his cruelty is the sort of ringing humanistic rhetoric Serling loved, but when the younger man points out that this was Sloan’s business too, Ramsie charges him, his face filling the screen as he shouts: “This is no one’s business! It belongs only to the best! To those who can keep it growing, producing, keep it alive. It belongs to us, yes. But in the future, it belongs to whoever can give it more.” Watching it at home, you worry that Ramsie might burst through the flat screen and bite your throat.

“It was like watching a very, very good movie,” Serling’s agent, Jerome Hellman, remembered. “It was so good in terms of content, and so good technically. You know how sometimes, everything clicks? Well, my memory of it is that everything clicked on that show. And you sat there and said, ‘Wow,’ and were totally riveted.”3 Paradoxically, however, this live performance that suggested a great movie became a fairly ordinary movie after Serling accepted an offer to adapt it to the screen for an independent production to be released through United Artists. Fourteen months after the TV premiere of Patterns took the country by storm, the screen version opened to respectful reviews and quickly disappeared from notice.

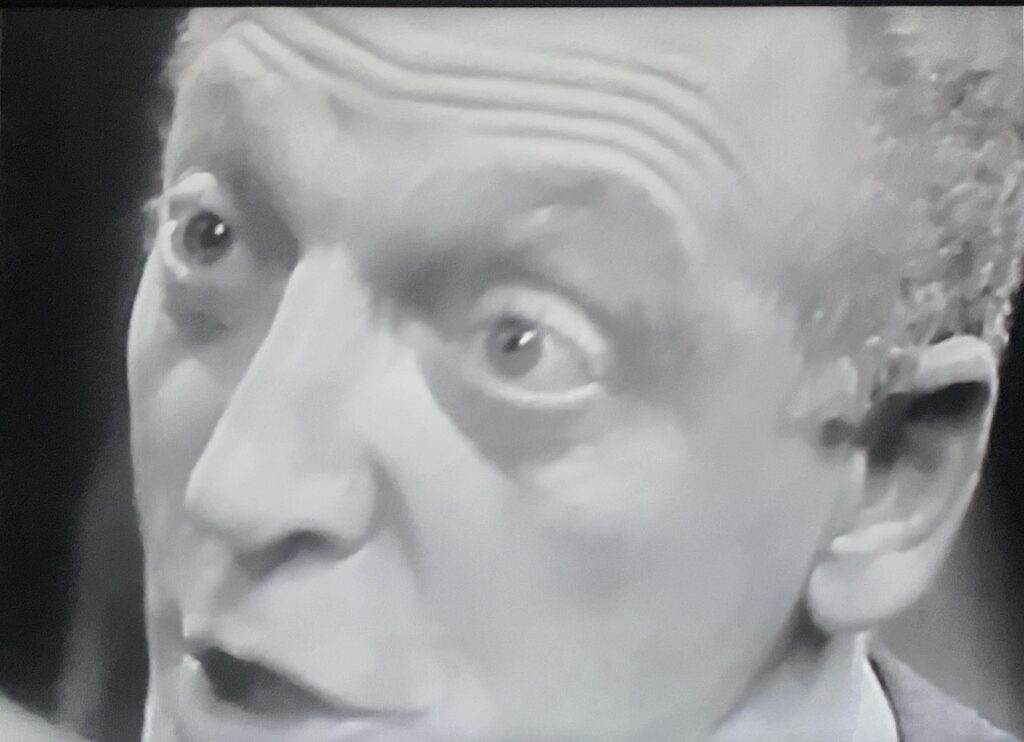

Staples (Van Heflin) and Walter Ramsay (Everett Sloane) confront each other in the 1956 screen version of Patterns.

Minus commercials, the teleplay had run a mere 52 minutes; nearly a half hour of screen time was added to bring it up to 80 minutes for a theatrical release. The text of the teleplay is preserved, and a variety of new scenes elaborate on the characters’ personal relationships. The most intriguing are those in which Briggs’s loyal, longtime secretary (Elizabeth Wilson) is reassigned to Staples in another dirty move to undermine Briggs. The most revealing is a late-night conversation between Staples and the targeted VP (played again by Begley but renamed Bill Briggs) in which the older man traces the history of (the renamed) Ramsay and Company from its namesake to his reptilian son. Other added scenes elaborate on Staples’s fraught relationship with his ambitious wife and Briggs’s neglect of his own teenage son, who has a drawerful of unused tickets to ballgames.4 These added scenes, though well-written, fatally slacken the pace, robbing Patterns of the tension that had made it so convincing on television as a tale of interoffice warfare.

Shot in black-and-white like its TV sibling, the movie proffers various establishing shots in a conventional gambit to open up the story; Fielder Cook, brought back to direct, introduces Fred Staples (played here by movie star Van Heflin) not in the lobby of the building but out on the street, admiring it from a distance. There are fewer close-ups, and none as extreme as those found in the TV broadcast. The close-up may have been a key storytelling device in the silent era, but once talking pictures came in, it was devalued in favor of the medium shot, which communicated characters’ relationships with each other as they conversed. On the big screen, Staples’s confrontation with Ramsay (Sloane, reprising his TV role) unfolds in conventional medium shots and close-ups that allow a more comfortable distance from the two angry men.

By the time Serling created The Twilight Zone in 1959, the TV industry was being co-opted by Hollywood as the networks phased out live drama anthologies broadcast from New York in favor of filmed series shot in Los Angeles. He moved to LA to produce the show, which was filmed at MGM Studios; such fantastic stories could never have been executed on live TV. After Twilight Zone came to an end, Serling enjoyed some success as a screenwriter, yet he was a bad fit for the movies. He had little instinct for telling a story in pictures—the true art of cinema—and like the radio dramas he grew up with, his screenplays could be talky and his dialogue too pointed. With Patterns, Serling proved that the small screen had a power all its own, though he did so primarily by failing to reproduce that power on the big one.

Footnotes

1 Newsweek, December 5, 1955.

2 Sander, Gordon F., Serling: The Rise and Twilight of Television’s Last Angry Man (New York: Dutton, 1992), 71.

3 Ibid, 104.

4 Cook wanted also to explore Walter Ramsay’s unhappy home life caring for an aging mother, but this idea was never pursued. Ibid, 112.

Edited by Olga Tchepikova-Treon