| John Costello |

All Through the Night plays at the Trylon Cinema from Sunday, September 7th, through Tuesday, September 9th. For tickets, showtimes, and other series information, visit trylon.org.

Although All Through the Night is primarily a comedy about small-time New York racketeers who become entangled in a spy ring working for the Nazi regime, the slapstick characters take moral positions for community, empathy, and democracy. The movie gives insights into contemporary fears regarding destructive foreign influence over recent migrants, as well as internal American divisions about isolationism, ones relevant in the modern political environment. The film is also interesting for its mention of Dachau, the first of the Nazi concentration camps.

The era’s filmgoers likely learned about these camps through newsreels, radio, and films released in 1940, such as Charlie Chaplin’s The Great Dictator (1940) and The Mortal Storm. By 1941, the New York Times described Dachau as “the most notorious of German concentration camps.” All Through the Night, then, uses Dachau as shorthand for Nazi brutality.

“I only eat cheesecake from Miller’s bakery.”

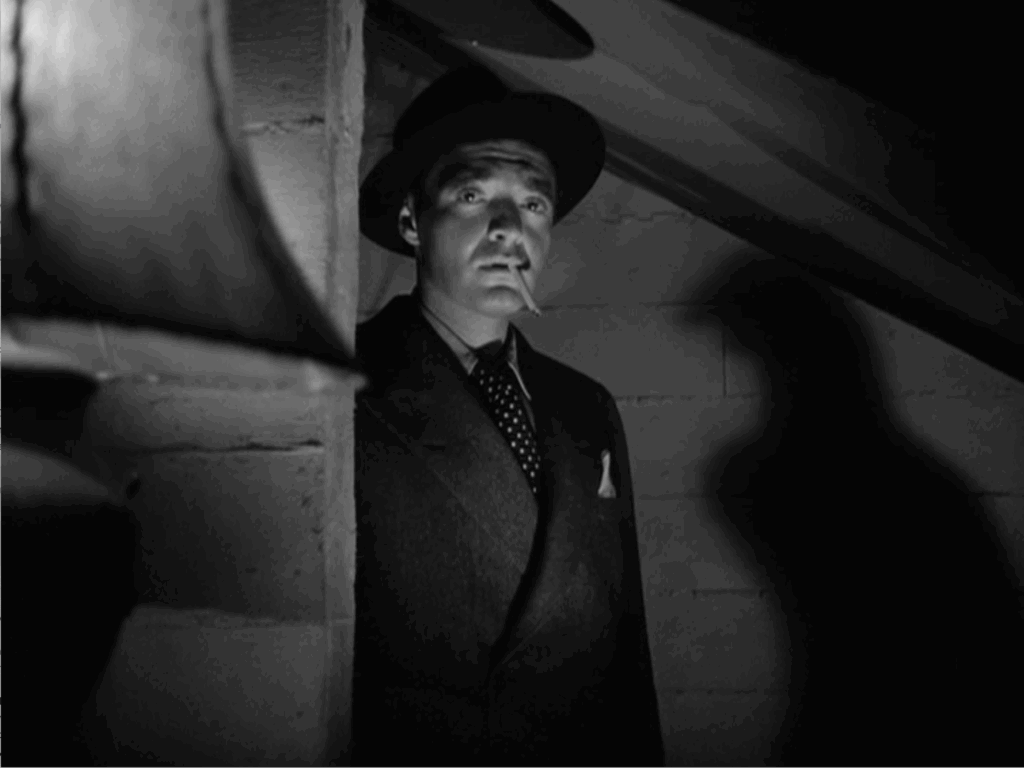

A simple description of All Through the Night: Gloves Donahue (Humphrey Bogart), a Broadway promoter and small-time neighborhood Irish American racketeer, is caught up in a Nazi conspiracy because of cheesecake (more on that later). Amid the film’s murders and fights, humor drives the story in the form of sight gags and quips along with certain stereotypes, mainly the portrayal of the Irish (the heroes) and the Nazi infiltrators.

Watching the film, I kept thinking about my adoptive and biological families, especially the Germans who migrated to the United States shortly before World War I, spoke German at home (according to the 1920 U. S. Census), and sent at least one son to fight for America in World War II. Because I’m adopted, I never knew these people who migrated from Baden and Hamburg, first to Imperial Russia and later to the American West. (I have a much better sense of direction.) They and other German Americans faced discrimination through both wars for their language and ethnicity, although not at the scale inflicted on Japanese Americans in the months after the U. S. entered World War II. These are injustices our current government seems determined to repeat by using purpose-built prisons and reactivated internment camps.

The earth swallowed him whole

The film begins with a tableau of children’s toy soldiers, pulling back to reveal men bickering over how Britain can defeat Nazi Germany. There is no mention of American involvement in the war, perhaps reflecting the majority opinion in 1941 that the U. S. should avoid entering the war. When Louie the waiter (Phil Silvers) criticizes the plans, one of the men, Sunshine (William Demarest), threatens to punch him. Louie removes his glasses, then complains that everyone has disappeared. It’s a simple gag to dismiss any tension in the scene.

Gloves arrives, and everyone settles to business in the cafe, reporting minor cons, gambling wins, and other details. When Gloves asks Louie about a bet on a boxer, Louie quips, “I love my mother, but she can’t fight, either.”

In addition to business, Gloves comes to the cafe for a specific cheesecake from Herman Miller (Ludwig Stossel), who runs a bakery with his wife Anna (Irene Seidner). The Millers are middle-aged people (about the age my immigrant German great-grandparents were at that time) who have known Gloves since he was a boy in a less prosperous neighborhood. From their names and accents, the reader can infer that they speak German and migrated, but not from where or when. (The actors playing the Millers are both Austrian.) The Millers are best understood as part of the waves of migration of German-speaking people of various ethnicities, religions, and countries of origin.

Donahue’s initial problems revolve around the cheesecake and his mother (Jane Darwell), who still lives above the Millers’ bakery, unwilling to move into the penthouse her son now can afford. She summons her doting son to the old neighborhood. (It’s a stereotype that the Irish Americans dote on their mothers, but my adoptive grandfather Costello, the grandson of Irish immigrants, started a green grocery with his mother and is buried beside her.) Gloves learns that Herman Miller has disappeared. The audience knows what happened to Miller, but not why, any more than Gloves understands why a mysterious woman (Kaaren Verne) suddenly appears at the bakery asking for Herman. When a policeman distracts Gloves, the mysterious woman disappears.

Later the same day, Gloves is summoned again, this time to a night club run by his rival, Marty Callahan (Barton MacLane). Gloves’ mother is convinced that she has found the mysterious woman at Callahan’s night club, and she’s causing a scene. Through his mother’s second intervention, Gloves becomes involved with the mysterious woman, a murder, and a sabotage ring. Because this is a comedy produced before the U. S. entered the war, you’d be safe guessing that Gloves triumphs in the end, but how he reaches that triumph is another matter.

Several plot points turn on luck or “keeping the gab going,” perhaps a more common term for what the Irish call blarney. People slapstick their way into capture, joke and quip, and stumble upon useful information. This is most true of the Irish American characters, whose main quality is not quitting. After Gloves is fingered for one of the murders, he has no choice but to pursue the mysterious woman and the conspiracy, as the film’s title declares, all through the night.

For some of the German-identified characters, choice plays a greater role. Miller resists a conspirator, calling the saboteurs murderers and criminals, incurring wrath. The mysterious woman’s actions unfold as intentional and not always hostile, once Gloves discovers her secrets. Gloves, too, undergoes a kind of transformation from reactive to argumentative.

By depicting the agency of the saboteurs’ unwilling victims, the film portrays a key, sympathetic difference that shouldn’t be lost on viewers: Not all German speakers are Nazis. In part, this aligns the film sympathetically with several of the actors, as well as various immigrants and refugees who had fled as Fascist forces claimed control from France to Poland, Norway to North Africa. But the film’s position is more than mere sympathy for one linguistic group.

“Round up everybody we know”

It’s inaccurate to call the film multicultural just because Gloves summons people of various ethnic backgrounds, including at least one whose only appearance is during a brawl. A better description is that the film is anti-isolationist.

In the beginning of the film, Gloves rejects involvement in the Nazi problem, telling Sunshine, his right-hand man, “That’s Washington’s racket.” Later, he argues with Callahan that the Nazis pose a threat to basic freedom. “They’ll tell you when to get up, when to sleep, what to eat, drink, wear, and read.” The argument convinces everyone in the room, not just Callahan. The scene is a call to arms meant as much for the audience as the characters onscreen.

Pre-war cultural contexts may illuminate the Irish American characters and the anti-isolationist message. By the time the film was produced in 1941, the Nazi regime had attacked and sunk neutral merchant ships and Navy vessels, including American ships. The FBI had broken the Duquesne spy ring, a group of saboteurs operating covertly in the United States. The key to foiling the plot was not Irish racketeers but a German immigrant, William Sebold, who had been aiding the Nazis only because, as happens in the movie, they were threatening his family in Germany. In the film, the Nazis hold a relative in Dachau to force cooperation.

The Irish characters would have been familiar because, among other things, of the popular sitcom about Irish Americans, Fibber McGee and Molly, which followed the unreliable husband-suffering wife formula. The use of Irish characters against isolationism seems to be targeted at a different Irish American cultural icon, Father Coughlin. Prior to the U. S.’s entry into the war, Coughlin, an Irish-descended priest, commanded a radio audience of one-quarter of the country’s population. His publication and radio show featured conspiracy theories, sympathy for the Nazi regime, and advocated isolationism. In terms of isolationism, he was in the majority. In April 1941, only 17% of Americans wanted U. S. troops sent to war. The latter number had hardly changed since a similar poll in April 1939 (LIFE 1939, 15).

In the film, the Nazi ringleader is aware of this isolationism and hopes to exploit it. “Already, we have split them into angry little groups flying at each other. Unconsciously, they are doing our work…. In a year, perhaps less than a year, they will all be taking their orders from us,” the sabotage ringleader boasts. The film confronts American isolationism by depicting the conflict coming to New York City.

When Gloves tells his men to round up everyone they know, he is gathering the people, the waiters, petty criminals, cabbies, gamblers, and workers. The people answer the call.

Partway through the film, a brawl ensues between the workers and the conspirators. The camera shifts to Louie the waiter, hunkered in a corner, an unlikely fighter with his thick glasses. Each time someone stumbles toward him, Louie says, “Sieg Heil.” If the other man responds in kind, Louie cracks the Nazi over the head with a baseball hat. It’s a funny moment, unless you like Nazis. The slapstick humor indicts them as mindless drones.

Although All Through the Night premiered in early 1942, after the U. S. entered World War II, the film properly belongs to the era when the country was officially neutral. Production finished two months before the U. S. entered the war, and the treatment of the Nazis as spies rather than wartime opponents would have been dated upon release. Despite this anachronism, which may explain its obscurity, All Through the Night is an enjoyable mix of suspense, action, and humor.

Works Cited

LIFE. 1939. “Polls on War & Peace, 1935-1939.” LIFE, April 17: 15.

Edited by Olga Tchepikova-Treon