| J.R. Jones |

The Intruder plays at the Trylon Cinema from Friday, September 19th, through Sunday, September 21st. For tickets, showtimes, and other series information, visit trylon.org.

If you’re sensitive to microaggressions, brace yourself for the macroaggression of The Intruder. This low-budget 1962 drama, about a small Southern town struggling to integrate its public high school, plunges viewers into the sort of casual white supremacism that fueled the horrific racial violence of the civil rights era. The white characters’ language may shock you, their attitudes may sicken you, and their courtly complacency in the face of harassment and bloodshed may shame you. Closely based on the court-ordered school integration of Clinton, Tennessee in 1956, The Intruder was courageous for its time, and in its ugliness, it still rings true—truer, in its way, than some contemporary dramas about that era, which observe their characters from a comfortable remove of six decades.

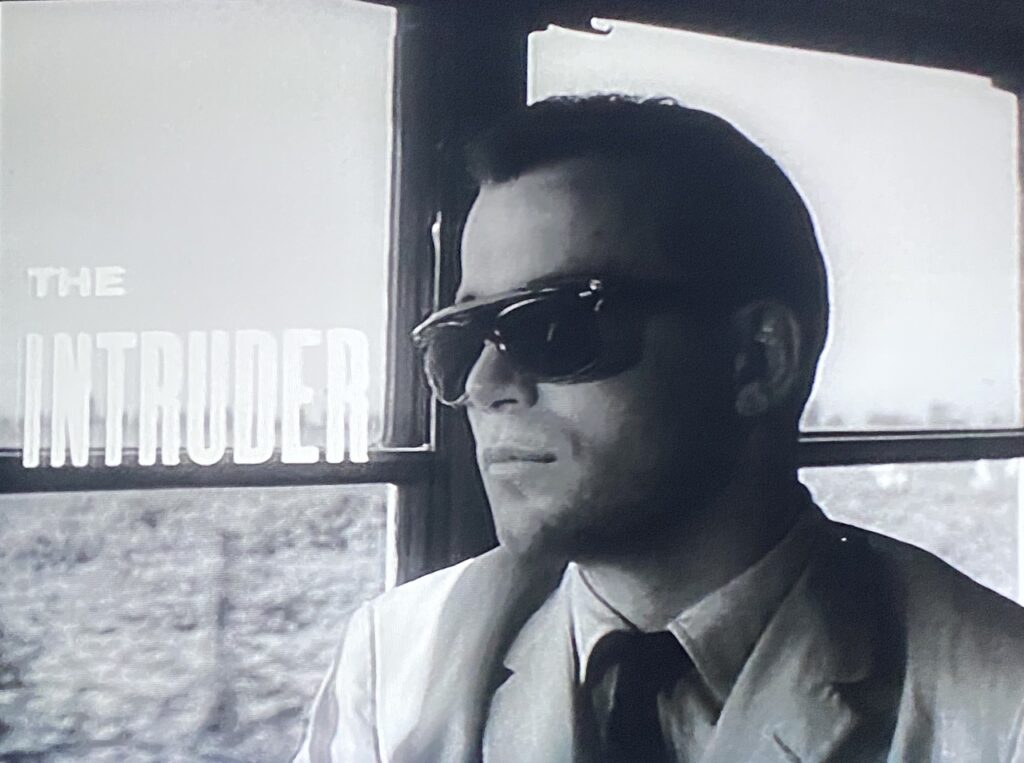

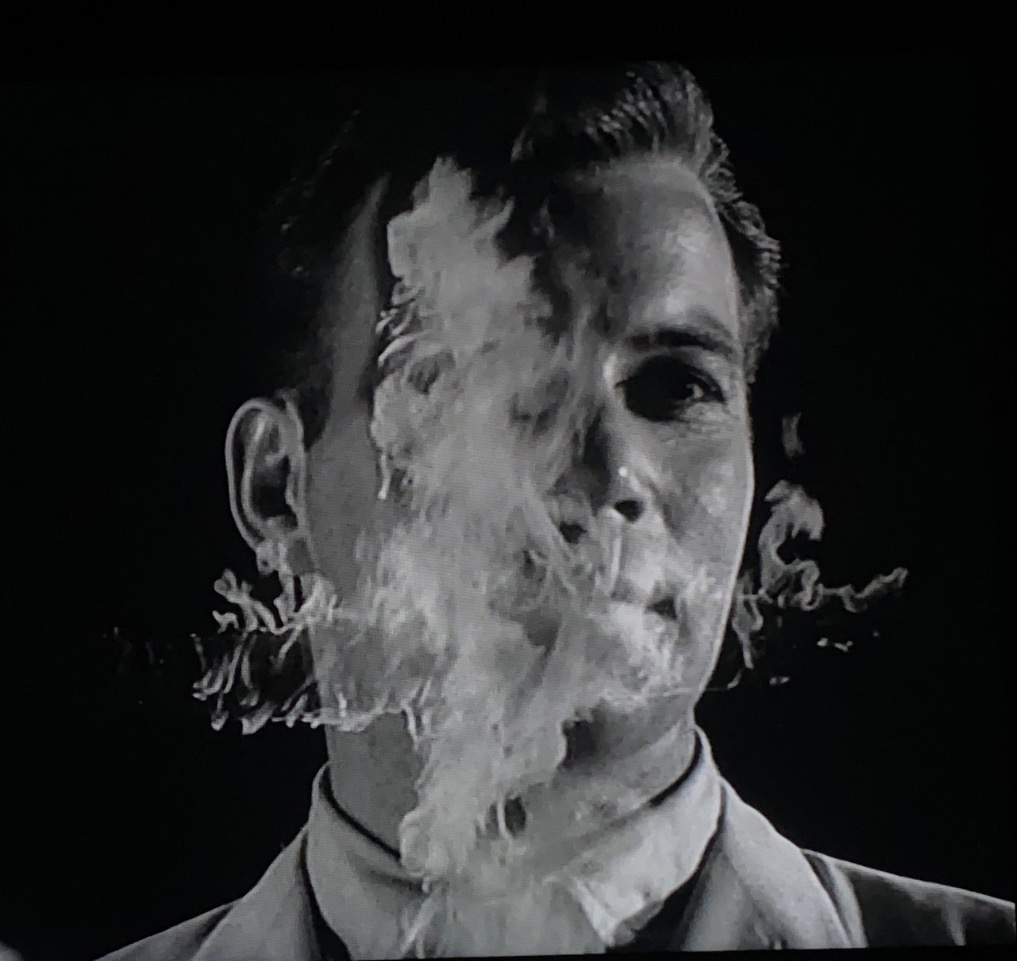

For a movie that rings true, however, The Intruder was steeped in duplicity. The wily exploitation filmmaker Roger Corman, best known at the time for his horror movies with Vincent Price, shot the film on location in southeast Missouri in July and August of 1961, carefully guarding some of the content from the locals he employed as extras. A young William Shatner, still five years shy of Star Trek, burns up the screen as Adam Cramer, a smooth-talking Yankee agitator who arrives in town to foment resistance to school integration. Yet, he delivered Cramer’s most incendiary speech to an empty town square, with reverse shots of the spellbound audience inserted later. The supreme irony of The Intruder is that in bringing the story to the screen, Corman resorted to the same sort of chicanery as his carpetbagging protagonist.

Cramer is based on a real-life figure: John Kasper, a young white supremacist and Columbia University graduate who arrived in Clinton by bus the Thursday before the school year began, checked into a hotel, made a series of phone calls to local segregationists, and began canvassing people on the street for their views on the situation. By Saturday he was able to draw a crowd of two dozen white men as he spoke on the courthouse lawn, urging them to keep their kids out of school and distributing literature with a photograph of a black man kissing a white woman. Arrested Sunday night for inciting a riot, he was set free by a judge on Monday morning and by noon was outside Clinton High School with a crowd of angry parents, denouncing the principal. That Thursday, at a rally before the Anderson County Courthouse, Kasper delivered a galvanic speech that enlarged his local following. Only 26, he began to develop a little fan club among the teens, especially the girls.1

An avowed anticommunist and antisemite, Kasper made numerous attempts that fall to ingratiate himself with local segregationists, but he wasn’t quite what he seemed. A devotee of poet Ezra Pound, Kasper had opened a bookshop and founded a little press in Greenwich Village to promote fascist writers, but he had also attended meetings of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, distributed its literature in his shop, dated black women, and enjoyed a romantic relationship with at least one. Much of this came out in November 1956, when Kasper was being tried for sedition in Anderson County. He was acquitted, but a month later, a bomb destroyed the meeting place of his little white citizens’ council, and he moved on to new segregationist battles in Nashville.

Charles Beaumont’s novel The Intruder, published two years after the events in Clinton, transplants Kasper’s story to the fictional town of Caxton, faithfully replicating his arrival, his maneuvers against the school integration, his ringing speech from the courthouse steps, and his concealment of his complicated past. To this, Beaumont added even more layers of deceit: at his hotel, Cramer befriends traveling salesman Sam Griffin and his wife, Vy, then seduces her while Sam is out of town. As the integration conflict intensifies, Cramer persuades Ella, a high school student with a crush on him, to claim she was assaulted by a black male student in the school’s basement. News of this spreads through town, and before long, the unlucky student is facing a lynch mob.

Corman bought the rights to Beaumont’s novel and screenplay, hoping to establish himself as a serious director after a decade of movies such as Teenage Caveman and Attack of the Crab Monsters, but he couldn’t win financing from his usual studio sources and put up most of the movie’s $80,000 budget himself. “I decided it had to be shot on location to be thoroughly credible,” he recalled.2 Mississippi and Alabama were ruled out as too hostile before Corman settled on the mid-South community of Sikeston, Missouri, with additional locations in neighboring Charleston and East Prairie. The lead actors were cast in L.A., but the minor players and extras were all recruited in Missouri “so the accents and inflections would be genuine.”3 Corman remembered “a sense of menace and danger” throughout the three-week shoot, the screenplay a carefully guarded secret:

Only Bill Shatner and I had copies of the complete scripts. Other versions of the dialogue were watered-down for public consumption. Then, on the days of the shoots, I’d run the real lines for the actors on the spot, explaining that some rewriting had taken place. I didn’t want to inflame the townspeople because we needed their cooperation.”4

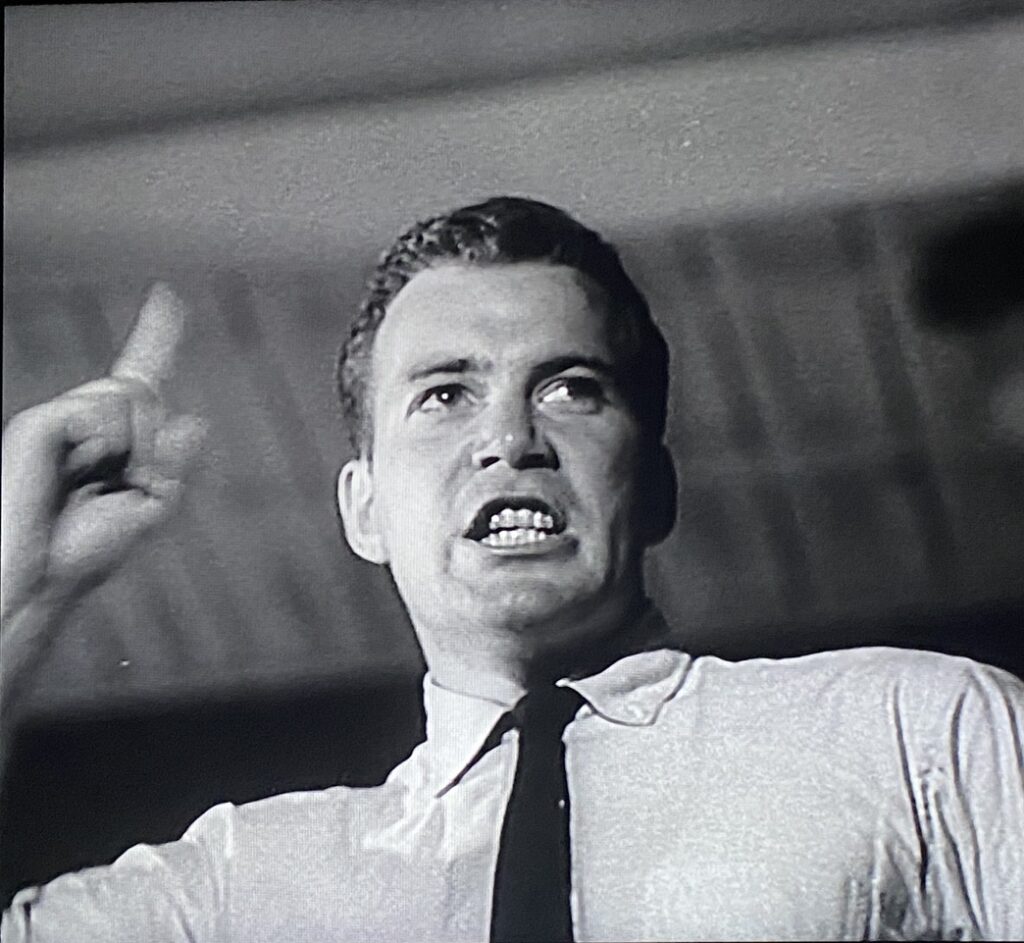

Cramer’s big speech at the county courthouse required an even more elaborate subterfuge. Hundreds of locals were recruited for the scene, and Corman trained his cameras on them from the direction of the courthouse first as Shatner spoke, knowing that, like most movie extras, they would get bored after a while and drift away. After the square had emptied, Corman reversed the cameras to focus on Cramer, with about a dozen extras posed in front of him, then shot close-ups in which Shatner, majestically clad in a white suit, delivered the real dialogue, ranting and raving like Mussolini.

At some point during the shoot, townspeople got their hands on Beaumont’s novel, and as Corman puts it, “things soon turned uglier.”5 Threatening letters arrived, and production equipment was vandalized. The sheriff of East Prairie shut down filming of the climactic scene in a local schoolyard, where the scapegoated black student is tied to a swing and taunted by the raging mob. “We know what you’re doin’,” Corman remembered the sheriff saying. “You’re trying to start a revolution. I don’t care about those papers. Get outta town or go to jail.”6 Thwarted at a second schoolyard, the director finally resorted to run-and-gun tactics, retreating to a country school the crew had scouted earlier to shoot without a permit and then defying the sheriff of East Prairie by going back to its school alone for an establishing shot he needed.7

The Intruder screens at the Trylon as part of a series on William Shatner, and his mesmerizing performance holds the film together. His Adam Cramer is a chameleon—gentlemanly with the older women at the hotel, direct and charming with his young followers, tough and conspiratorial with the good old boys who constitute the town’s segregationist wing. His southern drawl grows thicker with each passing day. Corman remembered shooting a scene in a café with Shatner and some older fellows from town, who ate up Adam Cramer’s racist rhetoric: “They knew it was a movie, they were paid extras, but they believed in Bill Shatner.”8 That onscreen blurring of fiction and reality is what makes The Intruder so disturbing and so valuable all these years later. But no one should never forget that its honesty was bought with a raft of lies.

Footnotes

1 For a definitive account of the Clinton High School integration, see Rachel Louise Martin’s A Most Tolerant Little Town (New York: Simon and Schuster, 2023).

2 Roger Corman with Jim Jerome, How I Made a Hundred Movies in Hollywood and Never Lost a Dime (New York: Da Capo Press, 1999), 98.

3 Ibid.

4 Corman, 99.

5 Ibid.

6 Corman, 100.

7 Footage from all three locations appear in the final sequence.

8 Corman, 100.

Edited by Olga Tchepikova-Treon