| Doug Carmoody |

Dead of Night aka. Deathdream plays at the Trylon Cinema on Wednesday, September 24th. For tickets, showtimes, and other series information, visit trylon.org.

The patriotic imperative to “support the troops” grew, like many other national neuroses, from America’s inability to reckon with the moral failures of the Vietnam War. To counter anti-war sentiment, the U.S. political establishment boosted effusive parades to “Support Our Boys in Vietnam.” Despite being patently stupid, the phraseology took root, eventually subsuming the discourse such that demonstrators against all future wars have had to take extreme pains to avoid coming off as anti-troop, lest they incur political slander.

Hollywood’s first forays into understanding the Vietnam veteran, though, were not trapped in this discursive quagmire. The first notes of vetsploitation sounded in the early 70s: Hi, Mom!, The Visitors (an early “Casualties of War” adaptation from Elia Kazan), and First Blood (the novel) each formed early moments of the movement that would crest critically and then commercially with Taxi Driver, Deer Hunter, and First Blood (the movie).

Bob Clark’s Dead of Night arrived in these fleeting moments before the veteran question had attained rigor mortis. The film’s flexible approach to its subject matter—an undead veteran returning to his suburban family—feels breathtaking in retrospect. By casting both the family and the veteran in an extremely harsh light, Dead of Night manages to traverse a path of bleak social criticism that has since been closed off.

No Place Like Home

The veteran in question operates in the first act more like a silent spotlight pointed at his family’s internal tensions than an active disruption of their suburban bliss. Andy is already dead, but he mostly just looks pale. It is his family that is decaying.

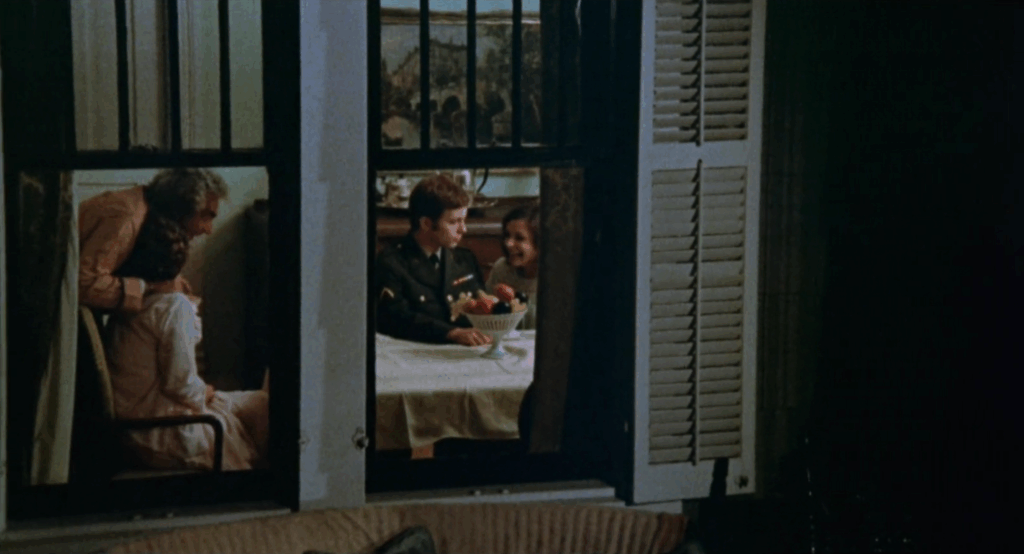

The energy is precisely as if a zombie shambled into one of the marital disputes from Cassavetes’ Faces; his mother and father are in fact played by the stars of that film (Lynn Carlin and John Marley). It’s a casting gag that seriously works. As in Faces, the spouses’ (brilliantly acted) fundamentally adversarial marriage is the germ from which a broader exploration of social malaise develops.

Andy here figures like the Freudian uncanny: “that class of the terrifying which leads back to something long known to us, once very familiar.” Before Andy really draws blood, his parents do, staging an escalating sequence of domestic spats in which they redirect the trauma caused by their son’s odd behavior straight at each other.

These sequences leverage Andy as a spectral presence who illuminates the gender antagonism that his family was barely able to conceal even in the opening sequence (in which a terse family dinner is disrupted by a death notification from the Army). In short order, his father is stomping around, exclaiming to his friends to ignore his wife: “this is my house.”

Staging this keen character drama helps to ground the acts of aggression that Andy is about to inflict on his hometown as a problem borne out of American society rather than inherited from abroad. As critic Robin Wood puts it: “it was not Vietnam alone that produced Andy’s monstrousness.”

The Undead Veteran: Post-Life Stress Disorder

Andy does come to disrupt his surroundings, once he settles in. His undeadness resembles a paranoid vision of PTSD in which a returning soldier, more than being incapable of assimilating back into society, brings an evil energy back from the imperial frontier.

The treatment of Andy’s undead idiosyncrasies as a PTSD analogue is familiar at first—he seems to have a difficulty expressing himself, turning taciturn and looking unwell at the sight of human interaction. The supporting cast members aren’t terrified so much as they are put off. A mouthy neighbor leans too far into a World War II story, and Andy causes a scene.

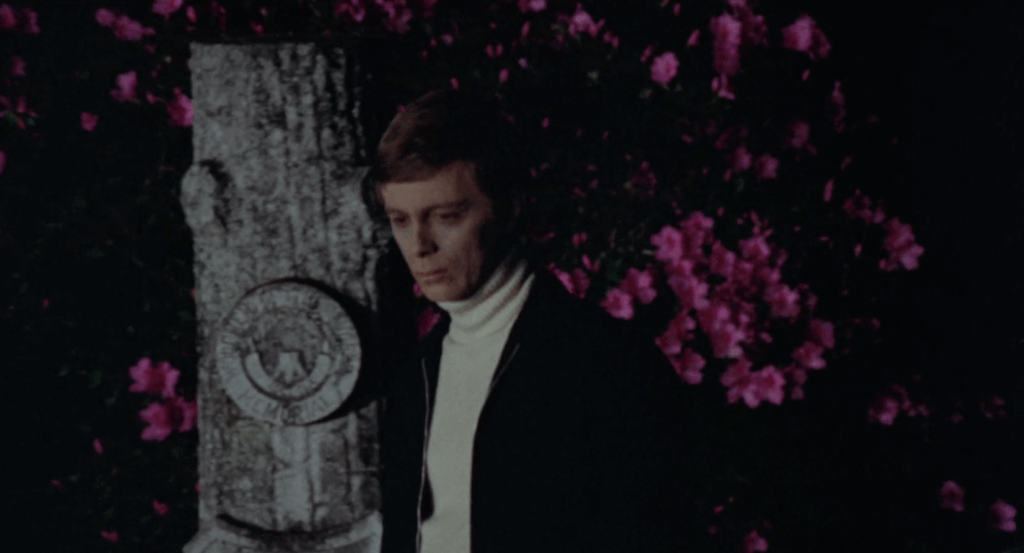

But if the other characters are slow on the take, the audience shouldn’t be: director Bob Clark employs a bagful of aesthetic tricks to emphasize Andy’s disjunction from his surroundings. Andy arrives at his family home by jumpscare; he erupts into the frame within a disjointed zoom effect. Clark supplements such newfangled techniques with more traditional horror compositions: Andy wears pale, vampiric makeup compared to his glowing (or occasionally liverspotted) family, and in one remarkable scene, he appears in a pink-chiaroscuro graveyard that contrasts starkly with the domestic beige tones permeating the rest of the film.

Painting Andy in jarring style serves as a perpetual reminder of his having killed an American truck driver in cold blood on his way home. Through this plot device, the film literalizes the perspective that anti-war protestors were (usually) falsely accused of in right-wing narratives—that the returning veteran is actually a murderer, he doesn’t deserve to come home, he shouldn’t be reassimilated into society.

As Andy’s violent nature surfaces, the shlock-Cassavetes family dynamic of the first act begins to appear more like a quaint form of violence waiting to be magnified by a new American archetype. By the film’s climax Andy is donning giallo-influenced sunglasses and black gloves, visually denoting his intent to escalate the patriarchal rhetoric of his family home into real misandrist murder.

The visual style then doesn’t merely generate an ominous mood. It paints the returning veteran as the bearer of a new inhumanity—someone who has lost a piece of themself and wants to spread the loss. As Andy puts it to an old family friend: “I died for you doc, why shouldn’t you return the favor?”

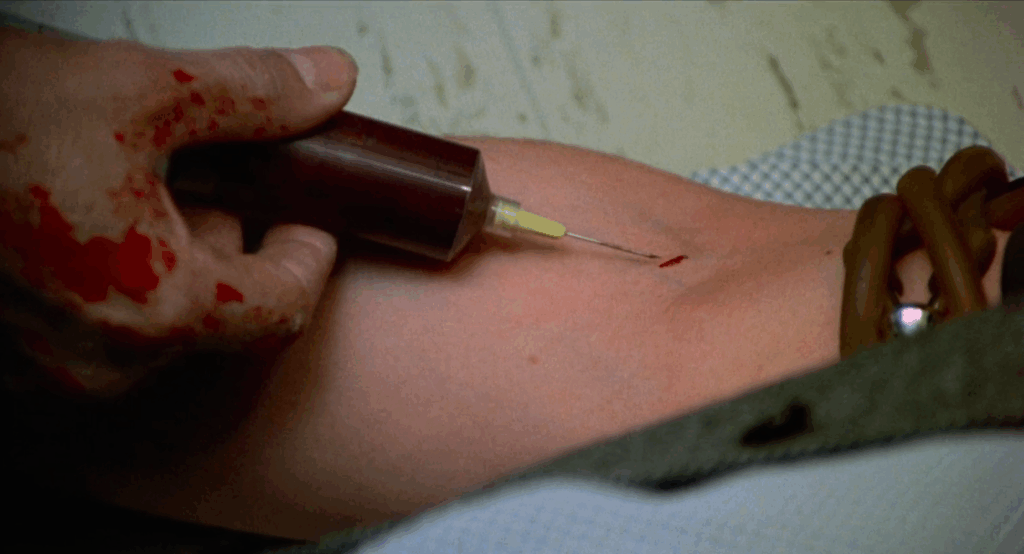

It is in precisely this context—the figurative transmission of loss and the literal transmission of blood—that Tom Savini’s superlative makeup work comes to the forefront of the film.

Blood Transmission

Where Bob Clark’s visual direction draws a distinction between the undead veteran and his living surroundings, Savini’s gore forms the very meeting point of the living and dead worlds. Like his father, Andy has difficulty expressing himself verbally, but comes to communicate with ease in the language of bloodletting.

Andy doesn’t look all that much better after desiccating his family friends. The blood he procures from the doctor only lasts him a day before he is leaking brown fluid from his forehead and wearing shades to cover his pus-laden eyes. The logic of the violence is reciprocal—with Andy seeking “returned favors” from practically everyone he runs into—but not sustainable in the fashion of the eternal undead. He’s a black hole.

Andy’s eventual collapse subsumes both the future of his small town and his family. He goes on a killing spree at a drive-in theater, eliminating a substantial portion of his town’s young people and leaving his sister Catherine traumatized. In quick order, his family is revealed as an absurdly patriarchal sham (his mother says the quiet part out loud: “I don’t care about Catherine”) and then deprived of both potential heads of household. Upon seeing his necrotic son, Andy’s father opts for suicide rather than confrontation. For his part, Andy has his mother drive him to a hand-carved gravestone and help him cover himself in dirt. He finds his appropriate level at six feet underground, to which his mother grimly acknowledges: “Andy is home.”

Such an unflinchingly negative portrayal of a monster veteran would be a difficult sell even ten years after the film’s production. By the 1980s, John Rambo had long been conscripted into the American culture war, coming to embody both the mythically spat-upon veteran and the archetypal returning prisoner of war. As the jingoist culture warriors planted their flag onscreen, the door seemed to close on any thought-provoking treatment of the veteran question.

Despite the genre’s reputation for exploiting difficult subject matter, American horror seems uninterested in pushing the boundaries of troop respect anymore. Uncle Sam, made two decades after Dead of Night and written by one of the foremost horror auteurs of the 1970s (Larry Cohen), demonstrates the cautious tendency that took hold of our national discourse. The film injects bland liberal critiques of the first Gulf War into the dialogue, but has a paint-by-numbers formal approach. Uncle Sam hews to conventions of both slasher films (allowing the audience to indulge in the monster’s patriotic slaying before ultimately condemning him) and war narratives (positioning a noble Vietnam vet opposite the cruel Gulf War vet). As a result, the film plays more as a slasher with vetsploitative trappings than anything subversive.

This comfortable, tactful approach feels hollow when compared to the political verve and open-ended exploration of either Cohen’s earlier scripts or Dead of Night. Rather than continuing the artistic legacy of the film, Uncle Sam seems to have inherited the vibe of the bleak final minutes: bloodless and dead-ended.

Edited by Finn Odum