| Jake Rudegeair |

His Motorbike, Her Island plays at the Trylon Cinema from Sunday, November 16th, through Tuesday, November 18th. For tickets, showtimes, and other series information, visit trylon.org.

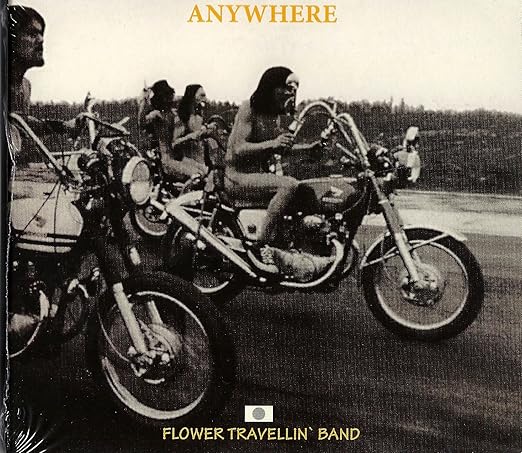

Yeah guys, this film has motorcycles. And lots of other stuff too.

Nobuhiko Ôbayashi’s His Motorbike, Her Island (1986) is a treasure from the annals of motorcycle cinema, bent with nostalgic longing, light on its feet, washing between full color and monochrome classic. It deploys the motorcycle like a mythical thing, elemental or divine, definitely carnal.

The motorbike has a long, storied history on screen as a Swiss-army icon that filmmakers have been whipping out since the early days of the twentieth century, in pictures like A Motorcycle Adventure (1912) or Mabel at the Wheel (1914). But it was The Wild One, released in December of 1953, that first delivered on that greaser-grime movie magic.

After WWII a wave of stylish biker films like The Wild One flowed into Japan, fueling the rise of the bōsōzoku (‘reckless driving group’) subculture, defined by frustrated youth, roaming the countryside on iconic machines. By the time Ôbayashi made HMHI, his American influences had collided with a visual language borne on the highways of home. The film is bursting with nostalgic power, riding down a desperate ache, hunting for some feeling long passed. The bike shines and purrs as an emblem of freedom, a sympathetic chariot for young love and lost souls.

The cranked-up surreality and experimentation of Ôbayashi’s much better-known Hausu (1977)—which to you might know even better yet as the Trylon Cinema’s annual Halloween movie—is super different from HMHI. Where the former is off-the-wall, skipping across time and place and form, the latter is (partially) grounded in gloss and interpersonal interest. Still, the two share some core DNA: An awareness of the camera for one, and the cultivation of a fantasy world that is fundamentally artificial in presentation, at the mercy of Ôbayashi’s eye—they both benefit from experimentation with color and kinetic editing. And they’re both wicked funny at times, albeit for very different reasons. They share Ôbayashi’s charismatic melodrama, as broad and primally pleasing as a T-plane Crank Triple (turns out motorcycle engines have great names). Both films charm in their harried performances, prolonged emotional displays, and out-of-control music cues.

Speaking of which, the music in HMHI deserves its own deep-dive. It’s a spinning, sickly sweet series of achy tracks, including a few numbers performed by the actors themselves. Music is the free, feeling-first artform that most amplifies all the wild trappings of HMHI’s cinematic romance.

Ôbayashi lovingly called HMHI his version of the “b-movie.” But motorcycle flicks and b-movies alike need to deliver the fun, and HMHI is a gas. It just feels good to watch, windy and bright, even when it veers into heartbreak (and horror). The narrator Koh (Riki Takeuchi in his very first film) is the monochrome dreamer who gets to fly on the titular motorbike, a deeply sick Kawasaki W3 that moans and thrums with “the sound of love.” Takeuchi has that fresh, impossible film face, youth radiating, especially dreamy in the gray tones and stark shadows. He’s eager, tense, fuming, contorting with lust, confused by his own desires. Then comes Miyoko (Kiwako Harada). She’s the island, the counterpoint, confident as a breeze, natural and vivid. But she’s also the one who coos “let’s be the wind,” stoking the fires of Koh’s restlessness. She wants to fly too, falling in love with the bike and the man, wrapped up in one exciting package. I’m not the first to observe the not-entirely-human love triangle, or how their desires are all filtered through chrome. It’s also Miyoko’s lust for the bike that leads her into danger, and further from the conventional road to long-term love. The lovers push and pull, accelerate and pass each other. It’s a sad and exciting antidote to the domestic life Koh’s being bullied into by the brute brother of his ex.

Between the languishing hearts and love songs, the naked bodies and childish courtships, the motorcycle holds the center. As a visual and thematic anchor, it’s hard to beat the bike. It stands in as a steed, a lover, a companion, and a dangerous symbol of octane modernity coming in hot on the heels of war.

Another film that iconized the bike is the 1986 animated masterpiece Akira, directed by Katsuhiro Otomo. But the vision of the motorbike in Akira was one of both the cool, quick power of youth as well as its fearsome destructive power. That film steers right into the horror of the nuclear age, the malformed post-war generation, and the rebellious divinity of technology that exhilarates and destroys. Akira is devoid of the nostalgic longing in HMHI, but they overlap in the indelible cool that only the motorcycle can deliver.

The steel horse was strong in the imagination of Japan for decades, enduring even into the 21st century with films like Hot Road (2014) and Shonan Junai Gumi (2020), long after the subgenre seemed to dwindle in Hollywood. Maybe there is something pure and primal in the bōsōzoku history of Japan that runs deeper than aesthetic fads or slicked back haircuts. The motorbike promises the wind, reducing the thorny path of life to the next bend, focused only on keeping up a head of steam, giving the kids a release from the less sexy trappings of modernity. Koh’s narration, removed from the color-confused events of his glory days, is reaching back for that wind. He’s snatching at it, listless but not regretful. Perhaps Ôbayashi sees the joy in crystallizing those windy days, catching a feeling and jarring it in film stock. He knows the truth, one of the load-bearing sorceries of cinema: You can always go back and take the past for another spin.

Edited by Olga Tchepikova-Treon

So good…

Thank you for the piece on bikes and for showing HMHI next week. Tickets await me.

Sold my bikes. A 1975 Norton 850 Commando and 73’ BMW r75/5 (“Toaster”) converted to 1000cc.

The Norton…..sheer joy. The Toaster, pure happiness.

Each offered hands on love of the now. Such solid focus in that cone of silence found on the bikes backed by their own unique sound flying along empty back country two lanes.

Nothing better than that old English throaty sound and that German silky smooth ride.

The days each was sold in 2012 and 2020?

Heartache and Emptiness.

What was I thinking to let those enriching beautiiful old girls go? Each bike a soulmate lost…

“You’re getting old.”

What do I think today?

“Dumbass move, John.”

See you at the movies!