| MH Rowe |

The Usual Suspects plays at the Trylon Cinema from Friday, November 28th, through Sunday, November 30th. For tickets, showtimes, and other series information, visit trylon.org.

Thank you for coming today. I want to say a few words about the strangeness of a film called The Usual Suspects, which was released in 1995 and over the course of the last 30 years has become a politely or even well-regarded classic of the “neo-noir” crime genre, though the film looks and feels like an above-average episode of The X-Files. (Above-average episodes of The X-Files, it must be said, are often worth your time.) The plot of The Usual Suspects has itself become a kind of meme, celebrated and parodied in equal measure. I’ll summarize the story only by saying that the film tells the tale of a criminal crew coming together to pull off several violent heists, culminating in a murderous and literally explosive finale in which all but one of them is killed. The lone survivor’s testimony, given under increasing duress to an aggressive and impatient U.S. customs investigator, serves as the viewer’s only source of information, often through voiceover, for almost everything shown on screen. The substance of The Usual Suspects therefore constitutes the account of Verbal Kint (Kevin Spacey), the one who got away. It’s his story.

The most interesting thing about The Usual Suspects is that almost none of it happened. I don’t mean that we are dealing here with a piece of fiction, though of course we are. What I mean is that the melodramatic “twist” ending of the film makes it clear that Kint has concocted many or perhaps all of the details of the story he has told. In a particularly comic bit, the lawyer Kint named, “Kobayashi,” turns out to be the name of the manufacturer of his interrogator’s coffee mug. Names and autobiographical details Kint shared over the course of his interrogation appear to have been lifted from names and photographs pinned to a corkboard on the wall of the police station office.

The implication couldn’t be clearer, though the film does not dwell on the point. Namely, everything we’ve learned about the crew of Dean Keaton (Gabriel Byrne), Fred Fenster (Benicio del Toro), Michael McManus (Stephen Baldwin), and Todd Hockney (Kevin Pollak) has been fabricated wholesale. We have, in effect, not watched a film, if a film is supposed to be a story that pretends to be real for our entertainment. Almost everything we’ve seen is instead a diegetic lie. In the world of the movie, in other words, Kint has been making it all up. We haven’t been told the story at all. We haven’t even really met the characters we’ve met. Nothing has happened. To take the movie seriously, you have to believe this.

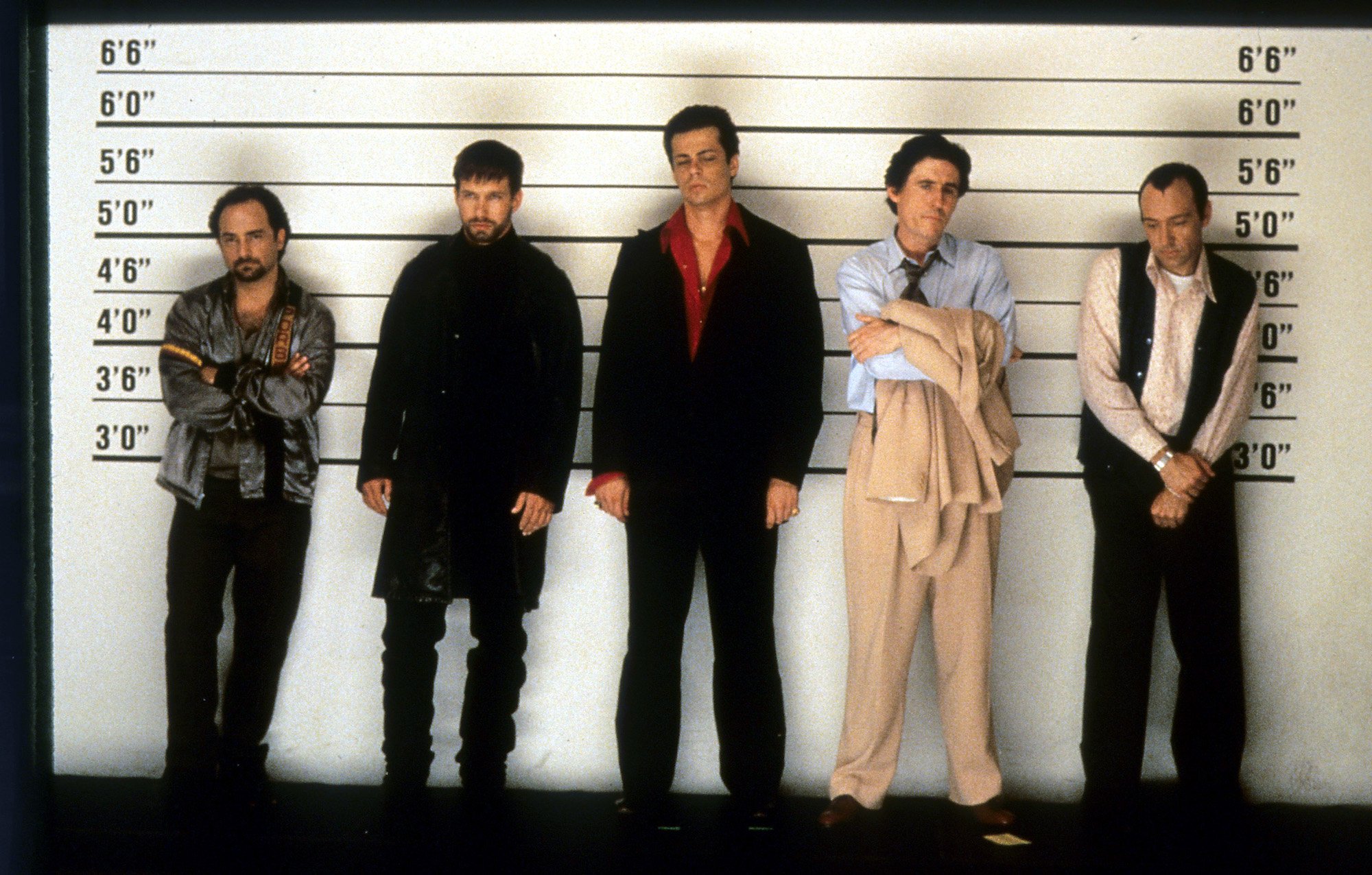

My point is that this narrative situation has a far uncannier effect than we might at first guess. Like the Quentin Tarantino movies that so dominated the 1990s, The Usual Suspects derives part of its talky charm from the feeling that the actors are hanging out, saying their lines, and laughing between takes. The film’s famous lineup sequence, where the characters can’t stop chuckling as they read out the phrase—“Hand me the keys, you fucking cocksucker”—that the cops have asked them to repeat, literally depicts this cracking up. The actors couldn’t stop laughing when they filmed the scene. The final version is sutured together from usable footage. To the extent that heist films are allegories for pulling off the feat of making a movie, The Usual Suspects delights in the process. It’s not a movie but a sketch held aloft by an impure sort of verbal energy. It elaborates a story only to pull out an eraser at the end and scrub away what felt so quick and forward moving.

There’s also the dizzy feeling that the entire film is a riff on the iconic Claude Rains line from Casablanca: “Round up the usual suspects,” which was already a line in a movie that felt self-conscious of being a line in a movie. Criminals in films like Casablanca and The Usual Suspects are types, not people. They serve a narrative purpose; they’re chaff not wheat. Christopher McQuarrie’s screenplay for The Usual Suspects accordingly implies a philosophy not unlike that you find in Tom Stoppard’s absurdist play, Rosencrantz and Guildenstern Are Dead, in which two minor characters from Shakespeare’s Hamlet are given their due, i.e. revealed to be trapped in an existential nightmare of narrative predestination. They can’t do anything but die at the scheduled time, while the entirety of Hamlet takes place offstage. Rosencrantz and Guildenstern are mere extras. Being an “extra” is, it turns out, a spiritual terror to eclipse all sense of human happiness.

Of all the extras who are the main characters in The Usual Suspects, Kint looks the most “extra.” He’s the most Rosencrantz and Guildenstern. But this only because it’s his story. He’s actually Hamlet, another man who talked too much. Like Hamlet, Kint decides what goes in and what’s left out. He orchestrates the show, the mousetrap, a play within the play, except his play within the play conceals his guilt, though eventually it reveals it all too emphatically. Or seems to.

Though Spacey is excellent as Kint, it’s exactly the kind of quiet-loud performance—sniveling then sarcastic, whispering and deceptive then shouting and wounded—that wins awards, which it did. Erected, too, on a foundation of imitated disability, with his palsied left hand and dragging left foot, Kint has an impressive weakness. He dares you to pity him or despise him. His is a coward’s ostentatious gravity. Kint and Spacey alike want to suck you in, make you sympathetic and irritated, the better to accomplish what the role demands, which is an overemphatic playing dumb to pull off a big con.

Spacey’s performance feels a little too wheedling now. It craves the Oscar. Of course, the point of Kint is that he’s a bigger con than you think. In reality, he’s the fabled gangster Keyser Söze, who everyone fears, who was pulling the strings behind the scenes all along. Söze wanted to kill everyone (for reasons that hardly matter) and get away with it. Which he does. As the film’s famous line has it, “The greatest trick the devil ever pulled was convincing the world he didn’t exist.” Just as with Spacey’s performance, you can feel this line making a self-conscious bid to be famous (I think it’s a variation on an idea from the French poet Baudelaire). The devil is, after all, a fallen man with a long and self-justifying story to tell.

It’s Benicio del Toro’s performance that feels to me, 30 years later, like it captures the soul of the film. Del Toro’s Fred Fenster is a nothing character. Tall, off-kilter, and suave, he projects physical comedy with alarming ease. The scene where he’s arrested, walking with fake nonchalance away from cops while picking absently at his ear, has the same charm of his instantly beloved dance while being arrested in this year’s One Battle After Another.

It’s the accent, though, above all. You can barely understand what del Toro is saying half the time. He sounds like he’s speaking in some Creole accent, the words elongated and sliding sideways out of his mouth. In this story, told the way it is told, del Toro’s accent, meaning Fred Fenster’s accent, suggests that the storyteller hasn’t really bothered to flesh out the character. He thought of the schtick and nothing else. Fenster feels half-remembered, half-forgotten, or half-made-up and half-imagined. He’s funny and charming, sure, but he doesn’t do all that much. He dies at the appointed time and has to repeat himself often when he speaks, as if his dialogue hasn’t quite been finalized. He’s the Rosencrantz and the Guildenstern of it all. A character who’s powerfully yet partly imagined, a throwaway man for a nothing movie about a story we’ll never be told.

Scholars have long debated the identity of this enigma named Keyser Söze. I submit, in the spirit of Fred Fenster’s accent, that he doesn’t really exist. He’s simply a way of talking, an accent, a schtick. Sure, a dying thug in the film may supply the details that turn into a police sketch of a man who looks like Verbal Kint, and the dying thug may insist that it’s Keyser Söze—but this is credible? It’s not credible at all! Roger “Verbal” Kint, if that is his real name, may well be an opportunist, a Cinderella, who found the perfect fairy tale to slip into and put on. That’s the key. It’s all a put-on. This movie never happened. You were never here. There is no Keyser Söze Memorial Lecture.

Edited by Olga Tchepikova-Treon