| Hannah Baxter |

How to Get Ahead in Advertising plays at the Trylon Cinema from Friday, December 5th, through Sunday, December 7th. For tickets, showtimes, and other series information, visit trylon.org.

How to Get Ahead in Advertising (1988) has a title reminiscent of a screwball comedy, maybe something starring Katherine Hepburn and Spencer Tracy. He’s a staid account executive and she’s a free-spirited graphic designer working at the same advertising agency. Forced to collaborate on a big account, they spar wittily over some layouts, grow on each other, fall in love, and ultimately enjoy a chaste, 1930s-style kiss in the glow of a light box. I can see it all now!

But that’s not at all what writer–director Bruce Robinson had in mind. Instead of Tracy and Hepburn, the movie stars Richard E. Grant and Richard E. Grant as Denis Dimbleby Bagley and his talking boil. Yes, it’s a comedy, but one that’s complicated by a generous helping of body horror and an anti-consumerism message that still resonates.

Ad man Bagley, driven to distraction as he tries and fails to come up with a campaign for a pimple cream, quits his job, loses his shit, and starts tossing out food and hygiene products in an effort to rid his life of capitalistic “contamination.” He tells his wife, Julia, that our desire for cars and hamburgers is destroying the rainforest along with our chance at health and happiness, a message that is so subversive of the 80s cult of greed in which he exists that a boil grows on his neck—and grows, and grows, first eyes and then a mustache—expressly to silence him.

This plot device is beyond unusual, but it works almost despite itself, thanks to a talented cast that commits so fully to the story that the power struggle between Bagley and the boil has real tension. The boil wins, taking over Bagley’s body and living his life the way it sees fit, including returning to the ad agency. The boil becomes consumed with perpetuating itself; it schemes to convince the public to cultivate their blemishes instead of curing them, and plans to impregnate Bagley’s wife.

Many of us worry AI will take our jobs, but at least we don’t have to worry about being replaced by our own pimples.

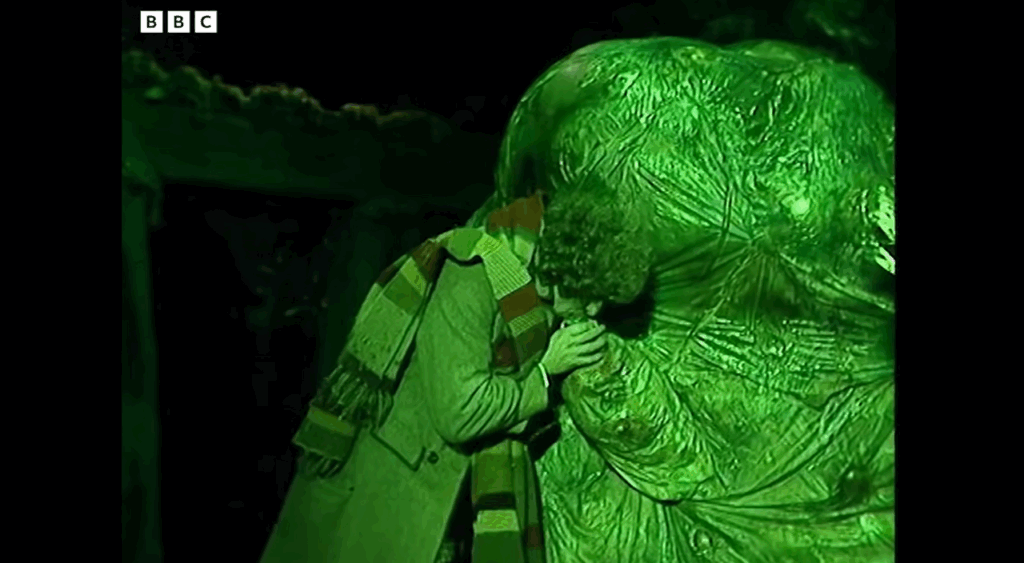

For a film’s audience to suspend their disbelief when things take a surreal turn as they do in this film, it helps to have decent special effects. Robinson puts a whole lot of faith in makeup and a series of animatronic faces—the face of the developing boil,1 and later, that of Bagley, imprisoned in his own body—that peek out from just above Richard E. Grant’s collarbone. Is Robinson’s faith misplaced? On the one hand, Bagley’s is certainly the most convincing talking boil I’ve seen on film. And when the boil grows to the size of Bagley’s head, and Bagley is reduced to a wizened little face on the boil’s neck, watching him plead for freedom or an audience with his wife is genuinely unsettling.

On the other hand, it’s possible I was conditioned to overlook special effects flubs during a childhood in which BBC television loomed large. I vividly remember, at eight or nine, stumbling upon Dr. Who for the first time. The episode was The Pirate Planet (1978) and featured a half-cyborg captain whose deadly robot parrot battles the Doctor’s own robot companion, K-9. This is peak Fourth Doctor, occurring in the fifth of seven seasons that starred Tom Baker and his iconic scarf and spanned 1974–1981. I was hooked.

I don’t ever recall, as a kid, thinking that I was putting up with hokey effects. Now, of course, little touches like a Dalek’s toilet-plunger arm or an alien appendage rendered in spray-painted bubble wrap fill me with nostalgic joy. But, I wondered, how would they look to kids who have never known a world without CGI?

There was only one way to find out. After consulting Reddit to select an episode with suitably cheesy effects, I settled on the couch with my kids to watch The Creature from the Pit (1979). I was prepared for complaints from the 10- and 8-year-old about slow pacing or stiff acting, or maybe a subtler dissatisfaction with the airless quality of outdoor scenes filmed in a studio. However, both kids became instantly absorbed in the story and started spinning theories about the eponymous creature right along with the Doctor and his companion, Romana. They picked up on the playfulness and humor that British sci-fi does so well. K-9 charmed them, and so did Romana, who looks very David-Bowie-circa-Hunky-Dory in this episode.

The kids’ reaction to the contribution of the BBC’s storied Visual Effects Department was more mixed. A gradual reveal of the creature that has been terrorizing inhabitants of the planet Chloris is meant to build suspense (à la Alien [1979]), but it falls flat. Our first sighting is when a blunted green appendage tentatively emerges from a passageway in the pit. (And yes, to the adult viewer it looks just as suggestive as it sounds.) We get a glimpse of an amorphous body further back in the passage. My 8-year-old felt let down: “That’s it?” My 10-year-old was more generous: “It’s creepy,” she said, although the casual observer might have noted she was not remotely creeped out.

The Doctor attempts to communicate with the creature. Why, oh why, did no one edit this sequence out?

In due time we get to see the entirety of the creature. It looks like a failed Jell-o mold but with a wrinkled skin like a pudding’s; it’s somewhere between The Devil in the Dark and dessert. Needless to say, the kids were not scared. But they did want to stay up past their bedtime to finish the program, just like I did at their age. As we watched the credits roll, my 8-year-old spotted the name of the visual effects designer. “That Mat Irvine did a bad job,” he said.

That Mat Irvine worked for the BBC throughout the 70s and 80s. He coauthored BBC VFX: The Story of the BBC Visual Effects Department along with colleague Mike Tucker. It’s the definitive (read: only) history of the department, which started out in 1954 with just two employees and grew to more than a hundred at its peak. Irvine and Tucker write that “even at a conservative estimate, the Department worked on over 20,000 programmes during its existence.” Its designer–builders wrung every drop of wonder they could out of the limited time and money they were allotted per episode. The Department closed in 2003, just a couple of years before Dr. Who was revived. (The BBC’s new Model Unit was involved in the revival along with outside companies.) As for the 650 or so episodes of “classic” Dr. Who, the Department made everything: masks and prosthetics, models and miniatures, monsters, props, painted backdrops, pyrotechnics, and, of course, animatronics.2

Speaking of animatronics, the BBC also created the 1981 TV adaptation of Douglas Adams’s The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy, featuring possibly the most disappointing animatronic prop in television history: the second head of galactic celebrity Zaphod Beeblebrox.3 Built in under six weeks, the head is homely thing, pasty and stiff, with hair that looks a lot like your childhood Barbie’s did after you gave her a trim. Operated by remote control, it can blink, move its lips, and nod…kind of. It wobbles around on actor Mark Wing-Davey’s shoulder looking ready to fall off at the slightest provocation. (“If you ran,” Wing-Davey remembers in the making-of documentary, “then the head bouncing up and down stripped the gears of the mechanism within it,” causing production delays.) Producer and director Alan J.W. Bell admits that “it was absolute rubbish.”4 Animatronics sometimes stray into the uncanny valley, but the head is stranded on the canny plain. Compared with this sad affair, Denis Bagley’s mustachioed boil is a marvel of engineering.

Can you tell which is the real head?

We learn in the making-of documentary that at first, producer/director Bell rejected the notion of televising the story. “There’s no chance that it could be done on television,” he remembers thinking. “The sets would be too big, and the effects would be too costly.” Wing-Davey agrees: “The head cost more than I got paid,” he states. At least his third arm was cheap: visual effects assistant Mike Kelt, who built and operated the head, also performed as the arm. He simply stood behind Wing-Davey and stuck his own arm through under Wing-Davey’s armpit.5

If you have read Douglas Adams’s books or listened to the radio dramas that preceded them, you might be thinking, “Gee, those would be difficult to adapt without CGI.” And you would be right. The BBC wanted to capitalize on the popularity of Adams’s work, which is understandable. But The Lord of the Rings was wildly popular for decades before Peter Jackson came along in 2001 and blew all our minds with the first true film adaptations of the series. Couldn’t the BBC have held off, too, and waited for technology to catch up to Adams’s imagination?

And yet, you can still get a special edition Blu-ray of the Hitchhiker’s TV series, including that affectionate making-of documentary. You can stream it on Apple Plus, too. It’s not as if the 2005 film adaptation, with its CGI bells and whistles, replaced the BBC series in fans’ hearts. The movie wasn’t, in fact, an upgrade. Nor would fancier technology necessarily improve How to Get Ahead in Advertising. The movie is not to everyone’s taste, certainly, but if you’re on board with the whole sentient pimple thing to begin with, you’ll want to see it through to the end, fakey effects or no.

Is it nostalgia that keeps fans coming back to media properties riddled with defective effects? Or is there something, well, special about these effects? I like to think they represent a kind of covenant between creators and fans, in which fans trust creators to provide solid stories about characters they care about, and creators trust fans to accept special effects fails and keep watching, saying, essentially, “I see what you were trying to do there. Carry on!”

Footnotes

1 The animatronics were created by a team of seven designers, including a foam specialist. The boil was voiced, incidentally, by Robinson.

2 Mat Irvine and Mike Tucker, BBC VFX: The Story of the BBC Visual Effects Department 1954-2003. Aurum, 2010.

3 Incidentally, Adams worked as script editor on Dr. Who for a year during the Tom Baker era, writing such memorable episodes as The Pirate Planet.

4 Kevin Davies, dir. 1992. The Making of “The Hitch-Hiker’s Guide to the Galaxy.” BBC, 1993. Blu-ray disc.

5 Davies, 1992.

Edited by Olga Tchepikova-Treon