| MH Rowe |

The Hour of Liberation has Arrived plays at the Trylon Cinema from Friday, December 12th, through Sunday, December 14th. For tickets, showtimes, and other series information, visit trylon.org.

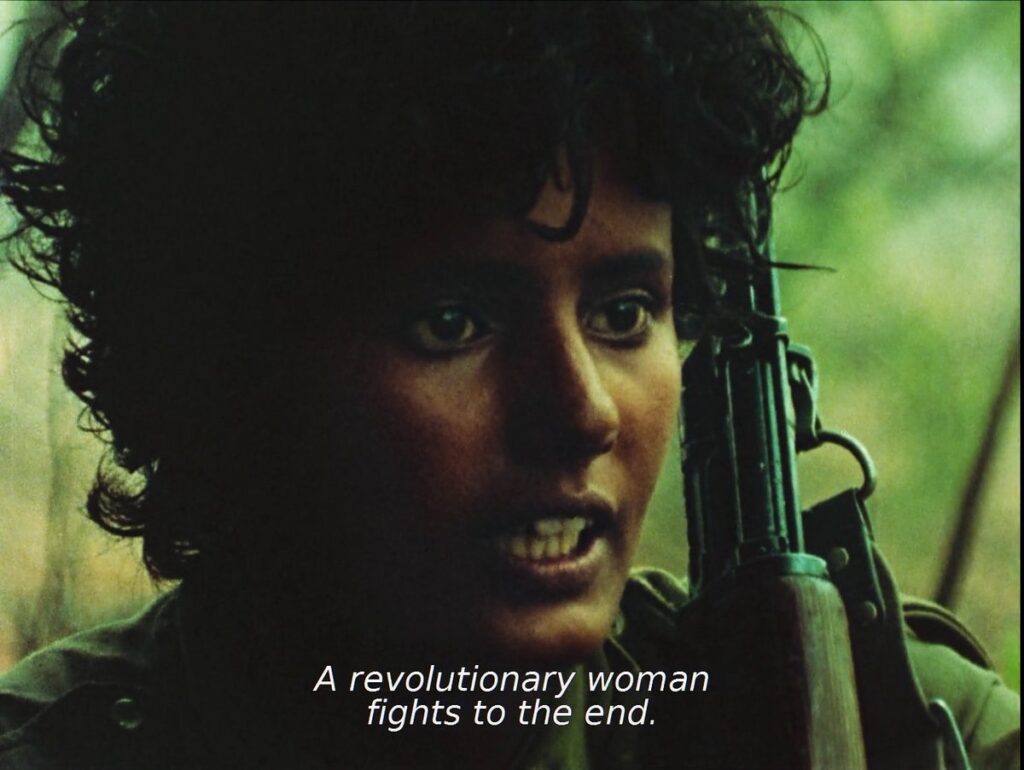

Some documentary films feel more like a document than an act of documentation. They may set out to study this or that topic, but in the end, they seem themselves like objects to study. To put it another way, I am inadequate to judge the regional history and politics presented in Lebanese filmmaker Heiny Srour’s 1974 documentary The Hour of Liberation Has Arrived. This short feature is essentially a piece of propaganda about a socialist and anti-colonialist revolutionary movement in southern Oman in the late 1960s and early 1970s. The political and social histories of that place at that time are almost wholly unknown to me. I’m not even sure whether Srour intended her film to reach an ignorant audience for the purposes of rousing their souls or to grip a knowing audience in an even more zealous sense of victory and promise. Her focus on the role of women’s liberation in the context of a broader uprising is nevertheless totally fascinating. Srour went to Herzogian, desert-crossing lengths to interview these people. Yet I feel provoked, half educated, and full of questions. Where, for instance, did these 15-year-old girls get all those guns? It seems clear to me that these are Soviet or Chinese weapons, as a quick internet search suggests, but the strong sense of global revolution in the film goes half articulated. I suppose I just don’t watch enough Communist propaganda. While I’m not sure Srour’s documentary is a great film, it’s a remarkable and well-made document. The best part is its mysterious and dignified gun-toting teenagers.

The documentary begins as a history lesson. Knowing little about Oman or Marxist politics in the Arabian Peninsula, I might have been surprised by the novelty of the instruction, but the story is an unfortunately familiar one. You’ve heard it before. First British colonial rule, then the control of oil markets. Violence and unrest ensue. When the British withdraw some of their colonial presence, they rely on a cozy relationship with the proverbial puppet government left behind. Oil profits are maintained. The population at large, riven by tribal conflict, is kept immiserated as it grows restive. When the British remove the sultan and install his son, Srour emphasizes, the situation only gets worse.

Meanwhile in the more remote south of the country, a militant uprising has taken control of an area called Dhofar. Though the British presence has diminished through a combination of withdrawal and retreat, it seems a real victory has been won—and for a Marxist political movement to boot. Men, women, and children at a seaside camp near the end of the film can be seen with little red books, which I assume, though I can’t say for sure, must be Chairman Mao’s collected sayings or anyway modeled after them. Anti-colonial and anti-tribal, the Popular Front for the Liberation of the Occupied Arabian Gulf (PFLOAG) works in Dhofar to raise consciousness, secure water access, maintain roads, and train women and men to be soldiers.

Srour has blessedly little interest in dramatizing this or that battle. Foot soldiers interest her, but as people: their attitudes and activities. Most of the shooting in the film depicts girls in training exercises. They’re often barefoot or in thin leather shoes. They disassemble and reassemble their weapons, practice marching, and talk on camera about their commitment to a new world order, in which they can fire guns instead of being married off at 15 with no further say in the course of their remaining years.

Such interviews are the most moving and fascinating feature of The Hour of Liberation Has Arrived. The first armed woman interviewed onscreen is Mona, a 15-year-old shepherdess, wearing a military uniform and with her hair cut short like the others to prevent the spread of lice. She speaks calmly and earnestly of women’s freedom, eager and a little scripted or maybe merely with the confidence of a good student. Something about the way she speaks feels well practiced. She says, “My husband took me here so that I may know my rights.” (I guess her husband didn’t know what those rights were.) Mona later appears on a poster shown in the film, a poster that seems to have been part of European political campaigns for socialist revolutionary causes around the world. Her striking face seems understood to be something like a slogan with a pathos all its own.

Another woman, Khiar, who is identified as 14 years old, speaks with a more spontaneous gleam in her eye about how women are oppressed twice. First, she says, they are oppressed by imperialism, as men are, but then also women are oppressed by men themselves, who sell them to their husbands. In this way, women are prevented “from serving the People.” Khiar, like Mona, is a good and intelligent soldier, obedient and clear-eyed.

There’s something thrilling and disturbing about this testimony. No doubt Mona and Khiar have experienced things beyond whatever has tested me in my life as a coddled middle-class American man. The apparently grassroots enthusiasm of these girls, however, sits alongside footage that makes clear the high level of political organization at work in Dhofar. Think of that seaside camp and the little red books, all the meetings, the gun technology. The idea that the most vulnerable members of a society—teenage girls sold into marriage—would be made armed and dangerous does indeed thrill our sense of justice. But in Srour’s film, it has too the ironic effect of making you sense that the leaders of the entire effort are close by, just off camera and not given clear attention. The deemphasis on leadership stresses it.

Another irony or perhaps simply a reality is at work here, too, at the level of leadership. Women and men in the film are seen being told that they have been oppressed by “several sultans.” At the same time, they are told that the PFLOAG has imposed limits of its own, on the sale of cows, for example. When the sultan offers to buy cows at a high price, says a PFLOAG spokesman, it’s a tactic to immiserate people further. The money that a man earns from the sale of a cow can’t be freely spent, since Dhofar is under blockade. The Front has therefore imposed a limit on the sale of cows for the good of impoverished cow owners. Government control in various forms and from various directions contends for the fate of these people.

And while these may be just observations on their part, something strikes me as fragile in the testimony of people who condescend to their own upbringing and residual traditions, which they refer to as “backwards.” A demonstration of an exorcism, which is mimed for the benefit of the camera, for example, claims to show a backward practice that has been rooted out. You wonder instead how wishful it is to say these things are gone. Has a great sweeping act of rationalism corrected everything all at once? The first generation to read and write yearns, understandably enough, to reimagine the world wholesale.

For all the questions it raises, Srour’s film is an open record of something barely alluded to in the Marxist and postcolonial histories with which I’m otherwise familiar. It stresses an earnest interest in literacy, agricultural training, and political organizing. In its soul, though, this is a film about young people who’ve been taught new habits of thought. The film’s narrators make it explicit too that social progress results from military victory. And “ideology,” they say, “guides the gun.” Though The Hour of Liberation Has Arrived emphasizes the role of women, it has a more general feeling, too: that of a children’s crusade. I wonder what became of them.

Edited by Olga Tchepikova-Treon