| Dan McCabe|

8 ½ plays in glorious 35mm at the Trylon Cinema from Sunday, January 4th, through Tuesday, January 6th. For tickets, showtimes, and other series information, visit trylon.org.

Note: This article contains spoilers for Federico Fellini’s 8 ½. If you want to see the movie without knowing anything about it, stop now.

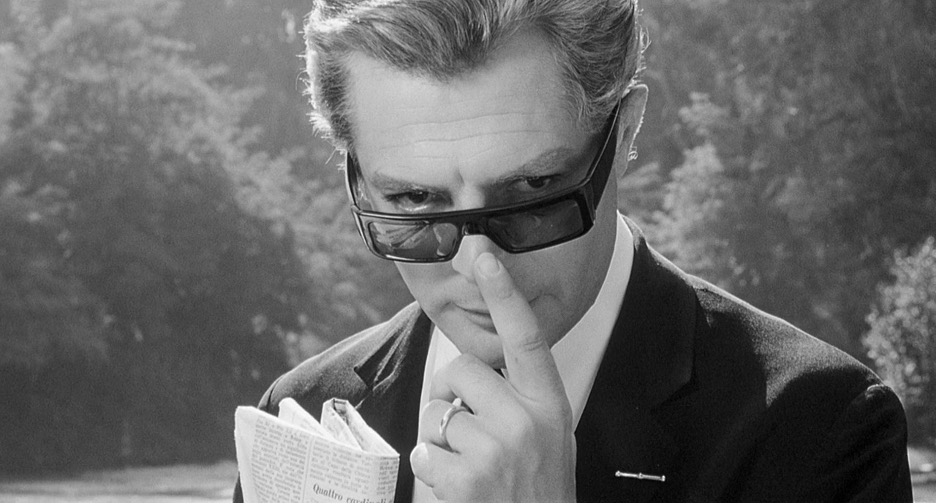

Guido (Marcello Mastroianni) hates the science fiction movie he’s making. He thinks such B-movie genre fare is cheesy and beneath him. Even worse, he can’t seem to figure out what movie he actually wants to make. Every idea he has gets shot down by his colleagues. Meanwhile, everyone wants a piece of him: his writer, his producer, his actors, his friends, his girlfriend, his wife, his wife’s best friend, random clergy, resort staff. They all want something from him, but he feels he has nothing of importance to give. No wonder he dreams about being trapped in a tiny, Italian car, suffocating on fumes while hundreds of people gawk at him.

We have more access to entertaining, good films than ever before. But if you watch many good films and television shows, and then you watch a truly great one, stark differences appear. One of the powers of a truly great film is that it reveals different themes depending on the context of your viewership. When I first watched Federico Fellini’s 8 1/2, a film Roger Ebert called the greatest movie ever made about filmmaking, saw a film about the nature of creativity and dreams. That’s what I intended to write about. But, watching the film over a decade later, I saw something else: a film about burnout.

At least that’s true now. When I first saw 8 1/2, I mostly focused on Fellini’s camera work and how he interspaced Guido’s dreams with his reality. Watching it now, Fellini moves into the background and Guido’s struggles come to the forefront.

Anouk Aimée as Luisa, Guido’s stylish, blunt, and somewhat estranged wife. Guido asks her to join him at the resort he’s visiting, even though his mistress is staying a nearby hotel.

Consider how everyone around Guido treats him. Guido might see them as beggaring him, but most of them are in awe of his talent and success. Well, except for his wife Luisa (Anouk Aimée), who’s not in awe of him. She just wants him to stop lying to her about his affairs and treat her as an equal. She wants the truth from him, but the problem is, Guido doesn’t know what the truth is anymore. That’s why he daydreams so much. That’s why he can’t make a movie.

It’s hard to feel too bad for Guido. He’s rich, famous, and powerful. He objectifies women and treats his co-workers with a cold distance. Yet, Fellini makes him a sympathetic character nonetheless. Contemporary audiences might be pulled in by the scenes from Guido’s childhood, or his complicated relationship with Catholicism. For me, it’s Guido’s burnout that pulls me in.

When you’re a mid-career professional, not just an attorney like yours-truly but an accountant, a doctor, etc., burnout is always around the corner. You might be fortunate not to feel it yourself, but you see it in those around you from time to time. I don’t know if burnout more common now than in previous years. Even if we didn’t quite have a name for it at the time, it was common enough in the 1960s for Fellini to make a movie about it.

Sandra Milo as Carla, participating in some bedroom roleplaying with Guido. The eyebrow makeup features prominently in the scene.

That’s why I find Guido sympathetic. On the surface, he’s a jerk, but he behaves this way because he’s depressed. The world around him wants so much from him, and he feels he has so little to give. He goes through the motions, coasting through the demands of fame and womanizing because he feels like he’s supposed to. Take the scene where he’s trying a bedroom roleplaying exercise with his mistress Carla (Sandra Milo). She’s into it, maybe a little too much, laughing the entire time. Guido is just lounging about. He finds her attractive, she’s catering to his whims, but he doesn’t really care. The mood especially goes south when Carla mentions that she’s just like one of the actors in his films. That’s the last thing he wants after a day of actors asking him for parts and butting into his creative process.

The classic example of burnout is the person who has worked too many hours without taking personal time, but I don’t think Guido feels burnt out because he’s working too hard. Most filmmakers keep long hours and many gush about how much they love their work despite the grind. Fellini was no different, with his boundless energy and attention to detail. Such passion can make hours of work fly by. Guido, on the other hand, is listless. If he had any passion for his work, he’s lost it.

The depression and burnout degrade his connections with others. He has personal relationships, sure, but he doesn’t value them. It’s hard to create something people can connect with without having those connections yourself. Consider the actors that try to talk to him. He treats them with the same detached aloofness, whether he’s working with them or not, because to him, they’re interchangeable. An actor’s director he is not.

Luisa is the only person in the movie (except for their mutual friend, Rossella (Rossella Falk)) who isn’t mesmerized by Guido. She doesn’t care that he’s a world-famous director. I can’t imagine she ever asked to be in one of his movies, she’s too sophisticated for that. No, as I noted above, she just wants the truth from him. He lies so effortlessly, and he knows she doesn’t believe him, but he does it anyway. It’s extremely disrespectful at best, as Luisa repeatedly reminds him.

Luisa, staring daggers at Carla across the outdoor restaurant at the resort.

There’s a scene in the resort’s restaurant when Guido, Luisa, and Rossella sit at a table. Carla walks in and takes a seat away from them. Guido swears to Luisa that he has no interest in Carla, and hasn’t spoken to her in years. Luisa rolls her eyes at the obvious lie, asking that Guido not embarrass her by assuming she’d believe his nonsense.

The problem is, Guido has lost track of what the truth is. Between the navel-gazing about his childhood, his fantasies of a harem (that turns on him, by the way), and his cold demeanor, he’s having trouble getting to anything approaching truth. I don’t think he’s losing his mind, he knows reality from fantasy. But he no longer recognizes truth from falsehoods on a philosophical level. It’s the root cause of his burnout.

So that’s why Guido feels overwhelmed, trapped, and lost (despite his millions of lira and legions of adoring fans). The world wants greatness from him, he wants it from himself, but greatness in art does not come from the muses. It comes from the artist’s truth, conveyed with the artist’s level of skill, and interpreted by the audience.

In the end, Guido reconnects with Luisa and accepts the world as it is. This is symbolized in the parade/dance scene that ends the film.

Guido learns that he cannot overcome his struggles without the people in his life. Where exactly does he figure this out? Fellini makes that unclear. For me, it’s when Guido imagines himself committing suicide. He only thinks about it out of sheer frustration, I don’t think he truly wants to die. But such an extreme thought opens his eyes to the world around him. It’s as if he tells his subconscious that enough is enough, and he has to find his way in this world that he still very much wants to live in, despite its imperfections.

The creative process and burnout are intertwined: to maintain the first and avoid the second, one must embrace, not shun, the world. And by that, I mean the world as it is. Not Guido’s fantasies or resentments, but creating something using his talents, in the actual world, with its imperfections and importantly, with its input. He needs the actors, the producer, and the other professionals. He needs the women in his life, both of them. Although Fellini makes it clear that he and Luisa have reconciled at the end of the film, Guido doesn’t cast out Carla.

Maybe Guido goes back to his depression and womanizing after the lights go out, but I don’t think Fellini intended to comment of the potential for backsliding. Rather, the theme is the radical power of acceptance, rather than the search for perfection, as the true source of creative freedom. Guido is burnt out not because he’s run out of ideas, far from it. It’s that he can no longer see those ideas for what they are. He pushes through the imperfections and contradictions to approach the truth.

Next time I watch 8 1/2, I might come up with something different to write about. I might key in on a particular shot, a particular line of dialogue, one of the flashbacks, etc. That’s the beauty of a truly great film; it changes shape the more you watch it. Check it out at the Trylon from January 4-6, 2026 and see what you can uncover within one of Fellini’s greatest masterpieces.

Edited by Olga Tchevpikoa-Treon