| Trylon Staff |

On December 1, the British Film Institute’s Sight and Sound magazine published their once-a-decade list of the greatest movies of all time, as selected by an international throng of respected critics and directors. As film lovers know, the decennial publication of this list is cause for celebration and dismay, nostalgic movie memories, think pieces about the state of cinema, and (most of all) fierce debate. There are good and bad things about canonical lists like these, but let’s focus on the good: they’re an excuse for cinephiles to share exuberantly in what they love the most.

So we at the Trylon wanted to follow suit and publish our own list of the greatest movies of all time, as selected by our staff of about 30 volunteers. Our parameters weren’t as strict as Sight and Sound‘s; respondents could select as many (unranked) favorite movies as they wanted, which could be voted on by other volunteers. The result is a unique, slightly chaotic compendium, from revered masterpieces to obscure cult classics and everything in between. Take a look at our list below, and the next time you’re at the Trylon, tell us what you think!

1. Mulholland Drive (David Lynch, 2001)

Lynch is at his most immersive and oneiric with Mulholland Drive, a sad, sultry dive into the nightmarish allure of Hollywood, so feverish it can fracture identities in two. Just as hypnotic as Lynch’s direction are a pair of brilliant performances by Naomi Watts and Laura Harring.

2. Stalker (Andrei Tarkovsky, 1979)

Taking the concept of “sculpting in time” to a new level, Tarkovsky fashioned an enigmatic blend of sci-fi and philosophy. Viewers are ushered into “the Zone,” an austere and foreboding world in which the characters’ (and humanity’s) greatest fears and desires are laid bare.

3. Tokyo Story (Yasujiro Ozu, 1953)

One of the most affecting uses of minimalism in film history, Ozu’s masterpiece tells the story of an aging husband and wife who visit their family in Tokyo, becoming aware of the irreversible rifts that have grown between them. Simple on the surface but endlessly profound, Tokyo Story becomes a moving meditation on human connection and the slow march of time.

=4. 2001: A Space Odyssey (Stanley Kubrick, 1968)

Kubrick’s famous adage, “If it can be written or thought, it can be filmed,” was proven true by 2001: A Space Odyssey, an epic vision that somehow seems to contain the mysteries of the cosmos. From the prologue set during the dawn of humanity to the monolith on the moon and the birth of the “Space Child,” the film is jam-packed with brain-teasing enigmas and hauntingly poetic images.

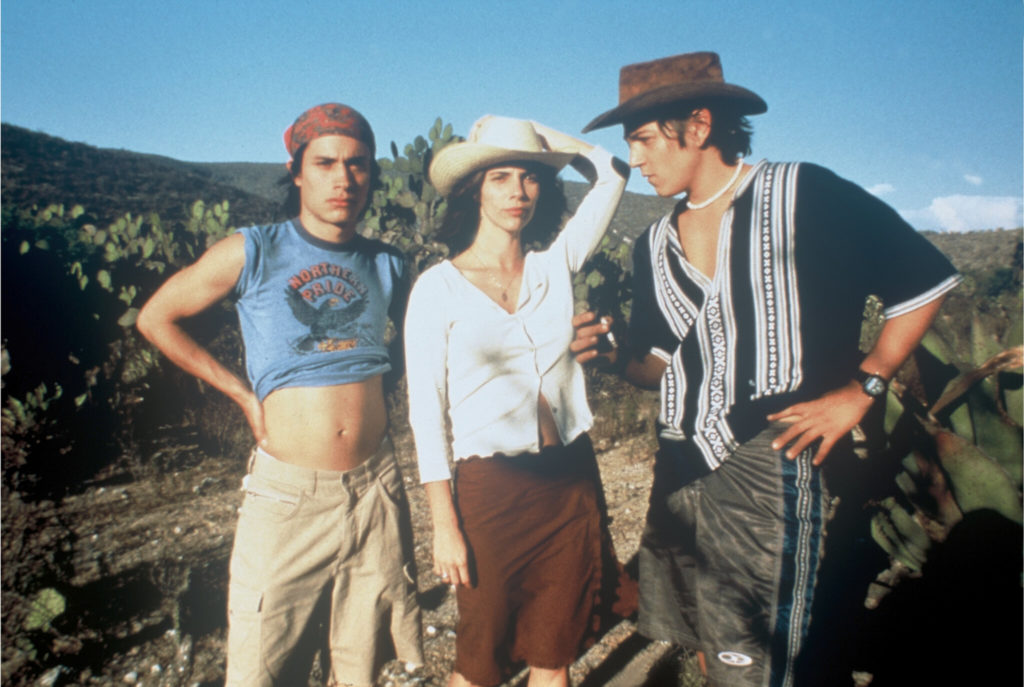

=4. Y tu mamá también (Alfonso Cuarón, 2001)

Cuarón’s road movie follows three characters – two reckless teenagers (Diego Luna and Gael García Bernal) and a recently married woman (Maribel Verdú) – as they drive around, flirt, have sex, discuss their flings and heartaches, and try to find a sense of direction in their lives. Meanwhile, the realities of Mexico in 1999 play out in the background.

=5. Blade Runner (Ridley Scott, 1982)

Like Fritz Lang’s Metropolis back in 1927, Ridley Scott’s Blade Runner reimagined how we see “the future,” envisioning a sci-fi dystopia that’s simultaneously gleaming and decrepit. Harrison Ford’s “blade runner” is enlisted to eliminate a group of replicants in 2019 (!) Los Angeles, leading to a moody neo-noir peppered with questions about what it means to be human.

=5. Children of Men (Alfonso Cuarón, 2006)

Another dystopian sci-fi vision, Cuarón’s Children of Men takes place in 2027, when years of infertility have pushed humanity to the brink of extinction. The arrival of the first pregnancy in 18 years rekindles a sense of hope amid the chaos. A marvel of mobile camerawork and action choreography, Children of Men welds top-notch Hollywood resources with ambitious ideas.

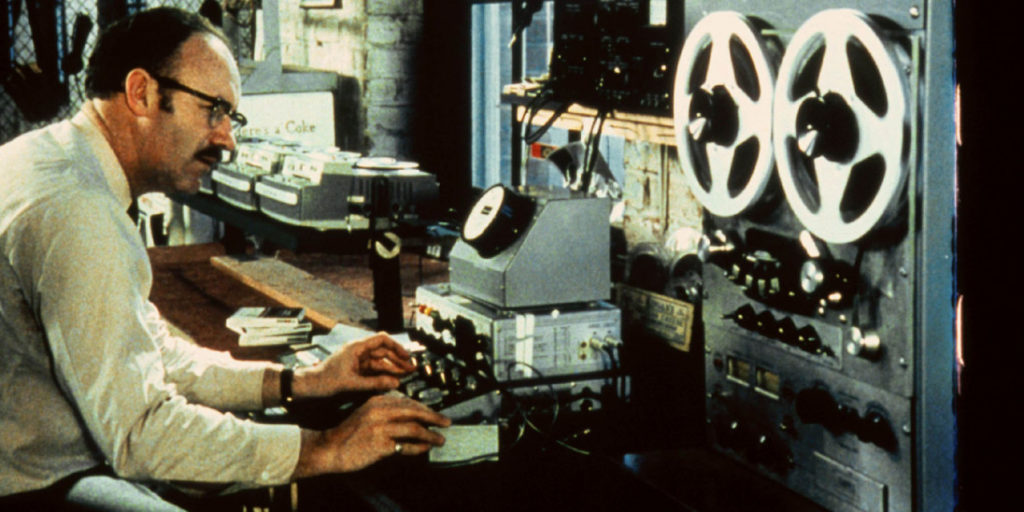

=5. The Conversation (Francis Ford Coppola, 1974)

By updating Antonioni’s Blow-Up to Nixon-era America (the president would resign four months after the movie came out), Coppola melded intense character study, political commentary, and a broader comment on how surveillance and technology have become ubiquitous.

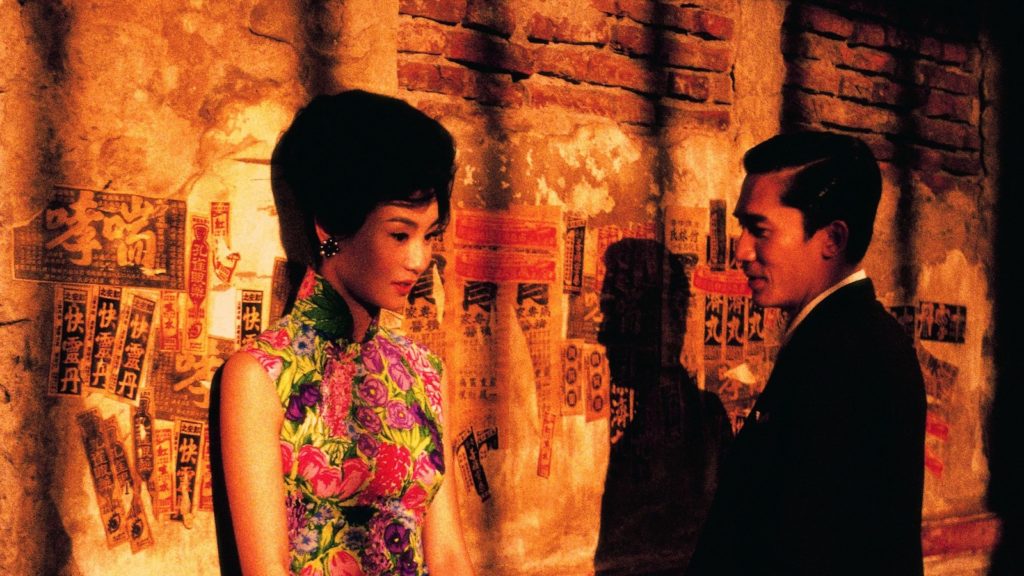

=5. In the Mood for Love (Wong Kar-wai, 2000)

A contender for both the saddest and the sexiest movie ever made, In the Mood for Love is built on distance and desire, absence and presence, intimacy and solitude. Set in the 1960s, with some of the most ravishing set and costume design you’ll ever see, Wong’s film casts a spell as inescapable as the love affair at its center.

=5. There Will Be Blood (Paul Thomas Anderson, 2007)

America’s age-old tension between religion and capitalism is vividly evoked by Paul Thomas Anderson in There Will Be Blood. Adapting the first few chapters of Upton Sinclair’s Oil!, the film is absurdly funny, brutally violent, and heartbreakingly sad in equal measure, enlivened by Robert Elswit’s elegant cinematography and a foreboding score by Jonny Greenwood.

=5. Touch of Evil (Orson Welles, 1958)

Trylon voters’ favorite Welles movie isn’t the one commonly cited as one of the best films of all time but his later neo-noir classic Touch of Evil. Beginning with one of the most famous and elaborate of all tracking shots, the film then details the clash between Mexican prosecutor Miguel Vargas (Charlton Heston) and corrupt police captain Hank Quinlan (Welles) in a small town on the U.S.-Mexican border. A stylish amalgamation of moral inquiry and B-movie sleaze, Touch of Evil is great enough to make you overlook the casting of Heston as a Mexican lawman.

=6. Beau Travail (Claire Denis, 1999)

No one makes movies like Claire Denis. In Beau Travail, she turns her eye on the French Foreign Legion in Djibouti, where the heated interactions between the isolated men in the squadron are simultaneously erotic, tragic, and touching. At times choreographed like a languid ballet, Beau Travail is hyperreal in its sensuous movements and relationships.

=6. Dr. Strangelove or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb (Stanley Kubrick, 1964)

Nuclear war has never been as hilarious as in Kubrick’s pitch-black comedy, which follows a group of disparate characters – including three of them played by Peter Sellers, most notably the wheelchair-bound, part-bionic Dr. Strangelove – as a hydrogen bomb is about to be dropped on Soviet soil. Scathing and hilarious in equal measure, this is one of the best political satires ever made.

=6. Lawrence of Arabia (David Lean, 1962)

David Lean brought new meaning to the word “epic” with Lawrence of Arabia, which follows T.E. Lawrence as he joins an Ottoman revolt against the Turks in the Middle East during World War I. The film’s opulent scope and extravagant style are matched by dense and complicated themes, which revolve around the nature of war and the meaning of national identity.

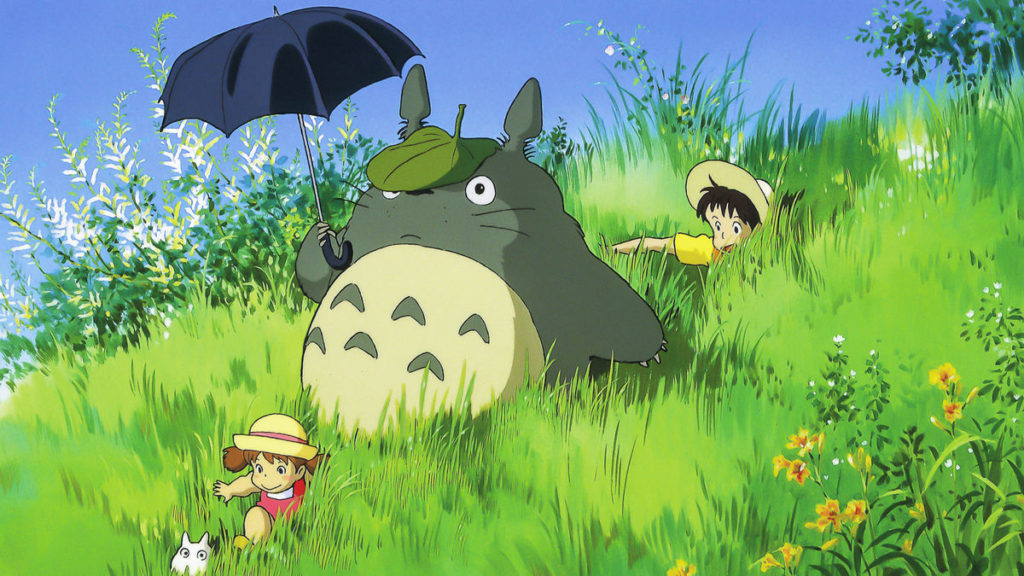

=6. My Neighbor Totoro (Hayao Miyazaki, 1988)

The pure wonder of childhood is captured by Miyazaki’s film, which follows two young girls in rural postwar Japan as they meet a menagerie of woodland creatures. Low on conflict but high on emotion, Totoro feels effortlessly magical, offering universal themes of friendship and environmentalism while connecting to Japan’s distinct history and animist beliefs.

=6. Once Upon a Time in the West (Sergio Leone, 1968)

The personal feud between the stoic outlaw Harmonica (Charles Bronson) and the villainous Frank (Henry Fonda) becomes an allegory for the transformation of the American West in Leone’s masterful Spaghetti Western. Elegant, exciting, and magnificently stylish, this also boasts one of Ennio Morricone’s greatest soundtracks.

=6. The Treasure of the Sierra Madre (John Huston, 1948)

A very different kind of Western, The Treasure of the Sierra Madre takes place (and was partially shot) in Mexico, where two desperate men (Humphrey Bogart and Tim Holt) partner with a grizzled prospector (Walter Huston) as they search for gold, inevitably leading to greed and violence. For his fourth feature as director, John Huston elicits terrific performances from the stellar ensemble (including his father), crafting a timeless tale with a perfectly cynical ending.

=7. After Hours (Martin Scorsese, 1985)

Scorsese’s black comedy is like Kafka mixed with the Marx Brothers, a hellish descent into the city that never sleeps (but still has nightmares).

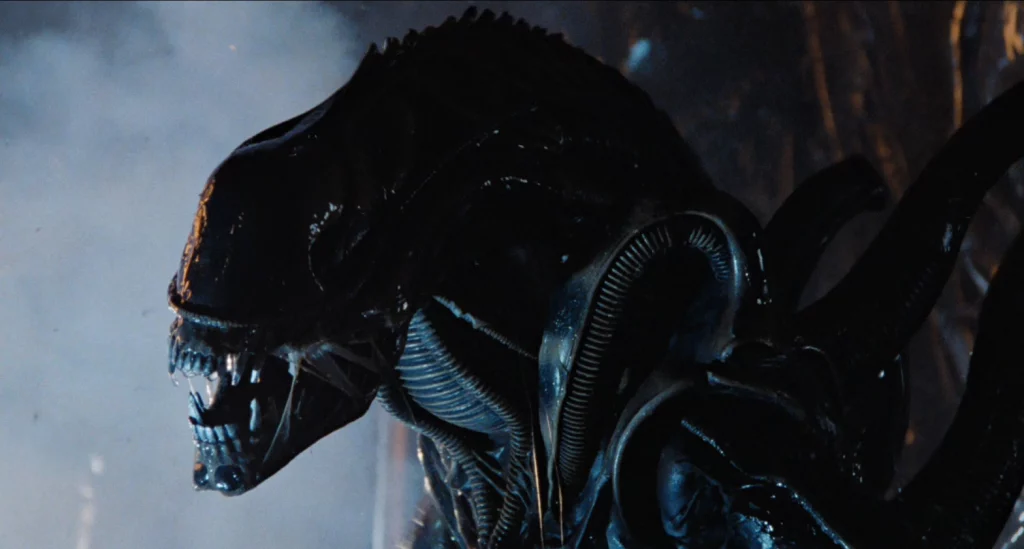

=7. Alien (Ridley Scott, 1979)

With iconic special effects designed by H.R. Giger, Alien is one of the best horror and science fiction movies of all time, ratcheting up the intensity to an almost unbearable degree.

=7. Cool Hand Luke (Stuart Rosenberg, 1967)

One of Paul Newman’s most legendary roles features him as an inmate in a Florida prison camp, refusing to submit to the system around him. The film reflected growing anti-establishment sentiment in response to the Vietnam War.

=7. The Lady Eve (Preston Sturges, 1941)

In the midst of his astonishing run of eight comedy classics from 1940-44, Preston Sturges teamed with Barbara Stanwyck and Henry Fonda for one of the funniest films from the Golden Age of Hollywood.

=7. Le Cercle Rouge (Jean-Pierre Melville, 1970)

Melville made some of the most stylish crime movies of all time but Le Cercle Rouge is among his best, a story of criminals and lawmen driven together by cruel twists of fate.

=7. McCabe & Mrs. Miller (Robert Altman, 1971)

Warren Beatty and Julie Christie star in this elegiac Western as a gambler and a prostitute who take charge of a fledgling frontier town. One of Altman’s most ambitious and idiosyncratic films (which is saying something).

=7. Playtime (Jacques Tati, 1967)

Abstract, modernist masterpiece, absurd silent comedy, deconstruction of the urban space…Playtime achieves many impressive feats. Jacques Tati built a miniature version of Paris to complete his singular vision.

=7. Suspiria (Dario Argento, 1977)

The pinnacle of style over substance, Dario Argento’s psychedelic giallo is one of the most visually extravagant movies ever made, frequently exploding into outbursts of color, light, and over-the-top violence.

=7. The Wild Bunch (Sam Peckinpah, 1969)

The rules of onscreen violence and visual form were rewritten by The Wild Bunch, a paean to outdated values of honor and justice. The rage and explosiveness of Peckinpah’s style was never as powerfully channeled as it was here.

=7. Airplane! (Jim Abrahams, David Zucker, and Jerry Zucker, 1980)

Setting a world record for most jokes per minute, Airplane! spoofs disaster movies, war films and everything in between.

=7. Blue Velvet (David Lynch, 1986)

Lynch responded to the failure of Dune (1984) with the most Lynchian film imaginable: a truly terrifying depiction of the evil within bucolic America.

=7. Hard Target (John Woo, 1993)

John Woo’s American debut is still one of his best, offering a fine showcase for Jean-Claude Van Damme’s action skills. (Leave it to the Trylon to include this one in the pantheon of greats!)

=7. The Last Detail (Hal Ashby, 1973)

Boasting arguably Jack Nicholson’s best performance, The Last Detail follows two Navy officers as they escort a young sailor to a naval prison in Maine, finding something close to friendship.

=7. Le Samouraï (Jean-Pierre Melville, 1967)

Melville’s other masterpiece was ranked the same by Trylon voters. Le Samouraï offers a fatalistic look at the criminal underworld, with an icy performance by Alain Delon.

=7. Nights of Cabiria (Federico Fellini, 1957)

Trylon voters chose Nights of Cabiria instead of 8½ or La dolce vita as Fellini’s best movie. Starring his muse Giuletta Masina as the titular prostitute, Cabiria is enormously moving as it balances the joys and miseries of life.

=7. The Shining (Stanley Kubrick, 1980)

Kubrick’s already appeared on our list in the sci-fi and comedy genres; why not add one of the scariest horror movies of all time to the mix? It’s intricate, darkly beautiful, and utterly terrifying.

=7. Vertigo (Alfred Hitchcock, 1958)

Few movies dive deeper down a rabbit hole of obsession, madness, and sexual control than Hitchcock’s sordid masterpiece. The analogy between dreams and cinema is more vividly evoked in Vertigo than nearly anywhere else.

Tied for 8th place

The following films all received three votes from Trylon volunteers.

The 400 Blows (François Truffaut, 1959)

All That Heaven Allows (Douglas Sirk, 1955)

American Movie (Chris Smith, 1999)

Black Narcissus (Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger, 1947)

Blow Out (Brian De Palma, 1981)

Close-Up (Abbas Kiarostami, 1990)

Con Air (Simon West, 1997)

Days of Heaven (Terrence Malick, 1978)

Do the Right Thing (Spike Lee, 1989)

The Fast and the Furious: Tokyo Drift (Justin Lin, 2006)

Grey Gardens (David Maysles, Albert Maysles, Ellen Hovde, and Muffie Meyer, 1975)

Groundhog Day (Harold Ramis, 1993)

Gummo (Harmony Korine, 1997)

Invasion of the Body Snatchers (Don Siegel, 1956)

John Wick (Chad Stahelski, 2014)

Kiki’s Delivery Service (Hayao Miyazaki, 1989)

Knives Out (Rian Johnson, 2019)

Mad Max: Fury Road (George Miller, 2015)

Night and the City (Jules Dassin, 1950)

Paths of Glory (Stanley Kubrick, 1957)

Pink Flamingos (John Waters, 1972)

Pulp Fiction (Quentin Tarantino, 1994)

Rio Bravo (Howard Hawks, 1959)

The Road Warrior (George Miller, 1981)

Snatch (Guy Ritchie, 2000)

Sorcerer (William Friedkin, 1977)

Tampopo (Juzo Itami, 1985)

Taxi Driver (Martin Scorsese, 1976)

The Thin Red Line (Terrence Malick, 1998)

The Thing (John Carpenter, 1982)

A Touch of Zen (King Hu, 1971)

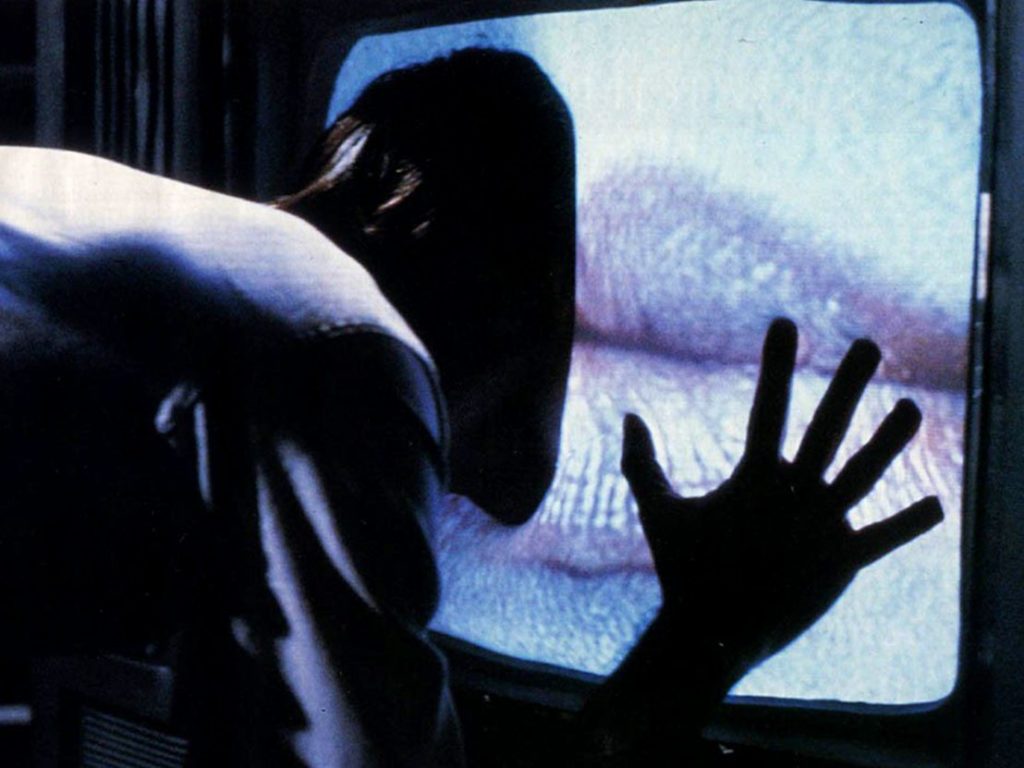

Videodrome (David Cronenberg, 1983)

Tied for 9th place

The following films all received two votes from Trylon volunteers.

8½ (Federico Fellini, 1963)

13 Going on 30 (Gary Winick, 2004)

Ace in the Hole (Billy Wilder, 1951)

Adaptation (Spike Jonze, 2002)

Amélie (Jean-Pierre Jeunet, 2001)

Anatomy of a Murder (Otto Preminger, 1959)

Army of Shadows (Jean-Pierre Melville, 1969)

Barbarella (Roger Vadim, 1968)

Batman (Tim Burton, 1989)

Blazing Saddles (Mel Brooks, 1974)

Boys Don’t Cry (Kimberly Peirce, 1999)

Casablanca (Michael Curtiz, 1942)

Caught (Maggie Kiley, 2015)

Certified Copy (Abbas Kiarostami, 2010)

Citizen Kane (Orson Welles, 1941)

City Lights (Charles Chaplin, 1931)

Cléo from 5 to 7 (Agnès Varda, 1962)

Clueless (Amy Heckerling, 1995)

The Dark Crystal (Jim Henson and Frank Oz, 1982)

The Dead Zone (David Cronenberg, 1983)

Double Indemnity (Billy Wilder, 1944)

Dragon Inn (King Hu, 1967)

Eraserhead (David Lynch, 1977)

Fire Island (Andrew Ahn, 2022)

The Flight of the Phoenix (Robert Aldrich, 1965)

The Friends of Eddie Coyle (Peter Yates, 1973)

Full Metal Jacket (Stanley Kubrick, 1987)

Ghost World (Terry Zwigoff, 2001)

The God of Cookery (Stephen Chow and Lee Lik-chi, 1996)

The Good, the Bad and the Ugly (Sergio Leone, 1966)

Goodbye, Dragon Inn (Tsai Ming-liang, 2003)

The Handmaiden (Park Chan-wook, 2016)

Heat (Michael Mann, 1995)

High Fidelity (Stephen Frears, 2000)

Hyenas (Djibril Diop Mambéty, 1992)

Ikiru (Akira Kurosawa, 1952)

Inherent Vice (Paul Thomas Anderson, 2014)

Irma Vep (Olivier Assayas, 1996)

It Follows (David Robert Mitchell, 2014)

It’s a Mad, Mad, Mad, Mad World (Stanley Kramer, 1963)

It’s Complicated (Nancy Meyers, 2009)

Jackie Brown (Quentin Tarantino, 1997)

Japón (Carlos Reygadas, 2002)

Jaws (Steven Spielberg, 1975)

The Killing (Stanley Kubrick, 1956)

The Killing of a Chinese Bookie (John Cassavetes, 1976)

The King of Comedy (Martin Scorsese, 1982)

L’Eclisse (Michelangelo Antonioni, 1962)

M (Fritz Lang, 1931)

The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance (John Ford, 1962)

M*A*S*H (Robert Altman, 1970)

Miller’s Crossing (Joel Coen, 1990)

Modern Romance (Albert Brooks, 1981)

Monsters, Inc. (Pete Docter, 2001)

Moonstruck (Norman Jewison, 1987)

National Lampoon’s Christmas Vacation (Jeremiah Chechik, 1989)

The Night of the Hunter (Charles Laughton, 1955)

Nosferatu the Vampyre (Werner Herzog, 1979)

One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest (Miloš Forman, 1975)

Ordet (Carl Theodor Dreyer, 1955)

Out of the Past (Jacques Tourneur, 1947)

The Palm Beach Story (Preston Sturges, 1942)

Pan’s Labyrinth (Guillermo del Toro, 2006)

Persona (Ingmar Bergman, 1966)

Pickup on South Street (Samuel Fuller, 1953)

Planes, Trains and Automobiles (John Hughes, 1987)

Portrait of a Lady on Fire (Céline Sciamma, 2019)

The Princess Bride (Rob Reiner, 1987)

The Princess Diaries (Garry Marshall, 2001)

Repo Man (Alex Cox, 1984)

Safe (Todd Haynes, 1995)

Save the Tiger (John G. Avildsen, 1973)

Scanners (David Cronenberg, 1981)

The Scary of Sixty-First (Dasha Nekrasova, 2020)

The Searchers (John Ford, 1956)

Seven Samurai (Akira Kurosawa, 1954)

Shame (Ingmar Bergman, 1968)

Shaun of the Dead (Edgar Wright, 2004)

Singin’ in the Rain (Stanley Donen and Gene Kelly, 1952)

Skyfall (Sam Mendes, 2012)

Smiley Face (Gregg Araki, 2007)

Sneakers (Phil Alden Robinson, 1992)

Spaceballs (Mel Brooks, 1987)

Spotlight (Tom McCarthy, 2015)

Straw Dogs (Sam Peckinpah, 1971)

Sweet Smell of Success (Alexander Mackendrick, 1957)

Three Amigos (John Landis, 1986)

Tie Xi Qu: West of the Tracks (Wang Bing, 2003)

Tremors (Ron Underwood, 1990)

UHF (Jay Levey, 1989)

Under the Skin (Jonathan Glazer, 2013)

The Wages of Fear (Henri-Georges Clouzot, 1953)

What a Girl Wants (Dennie Gordon, 2003)

What We Do in the Shadows (Taika Waititi and Jemaine Clement, 2014)

Wings of Desire (Wim Wenders, 1987)

Woman in the Dunes (Hiroshi Teshigahara, 1964)

The World (Jia Zhangke, 2004)

Young Frankenstein (Mel Brooks, 1974)

All films voted for

The following films all received one vote from a Trylon volunteer.

Amadeus (Miloš Forman, 1984) ● American Pop (Ralph Bakshi, 1981) ● The Apartment (Billy Wilder, 1960) ● Baby Boy (John Singleton, 2001) ● Badlands (Terrence Malick, 1973) ● Bananas (Woody Allen, 1971) ● Bicycle Thieves (Vittorio De Sica, 1948) ● Brazil (Terry Gilliam, 1985) ● The Conformist (Bernardo Bertolucci, 1970) ● Creature from the Black Lagoon (Jack Arnold, 1954) ● The Dark Knight (Christopher Nolan, 2008) ● Dawn of the Dead (George A. Romero, 1978) ● Days (Tsai Ming-liang, 2020) ● Dead Man (Jim Jarmusch, 1995) ● Die bleierne zeit (Marianne and Juliane) (Margarethe von Trotta, 1982) ● Dirty Ho (Lau Kar-leung, 1979) ● Dishonored (Josef von Sternberg, 1931) ● Distant (Nuri Bilge Ceylan, 2002) ● Diva (Jean-Jacques Beineix, 1981) ● Donnie Darko (Richard Kelly, 2001) ● Drive My Car (Ryusuke Hamaguchi, 2021) ● The Driver (Walter Hill, 1978) ● The Eight Diagram Pole Fighter (Lau Kar-leung, 1984) ● The Empire Strikes Back (Irvin Kershner, 1980) ● Face/Off (John Woo, 1997) ● Farewell My Concubine (Chen Kaige, 1993) ● Female Trouble (John Waters, 1974) ● The Fisher King (Terry Gilliam, 1991) ● For a Few Dollars More (Sergio Leone, 1965) ● Freddy Got Fingered (Tom Green, 2001) ● The Graduate (Mike Nichols, 1967) ● The Great Dictator (Charles Chaplin, 1940) ● Gremlins 2: The New Batch (Joe Dante, 1990) ● Hackers (Iain Softley, 1995) ● Hana-bi (Fireworks) (Takeshi Kitano, 1997) ● Henry & June (Philip Kaufman, 1990) ● High and Low (Akira Kurosawa, 1963) ● House in the Fields (Tala Hadid, 2017) ● Infernal Affairs (Andrew Lau and Alan Mak, 2002) ● If… (Lindsay Anderson, 1969) ● Johnny Guitar (Nicholas Ray, 1954) ● Karamay (Xu Xin, 2010) ● The Kid (Charles Chaplin, 1921) ● Kiss Me Deadly (Robert Aldrich, 1955) ● La Vie en Rose (Olivier Dahan, 2007) ● Les Vampires (Louis Feuillade, 1915) ● Letter from an Unknown Woman (Max Ophüls, 1948) ● The Life Aquatic with Steve Zissou (Wes Anderson, 2004) ● Losing Ground (Kathleen Collins, 1982) ● The Man Between (Carol Reed, 1953) ● Marie Antoinette (Sofia Coppola, 2006) ● Metropolis (Fritz Lang, 1927) ● Mikey and Nicky (Elaine May, 1976) ● A Moment of Innocence (Mohsen Makhmalbaf, 1996) ● Mon Oncle (Jacques Tati, 1958) ● My Night at Maud’s (Éric Rohmer, 1969) ● Nausicaa of the Valley of the Wind (Hayao Miyazaki, 1984) ● News from Home (Chantal Akerman, 1976) ● The Night House (David Bruckner, 2020) ● Nomad (Patrick Tam, 1982) ● Northern Lights (John Hanson and Rob Nilsson, 1978) ● Oldboy (Park Chan-wook, 2005) ● Open Your Eyes (Abre los ojos) (Alejandro Amenábar, 1997) ● Paris, Texas (Wim Wenders, 1984) ● Pather Panchali (Satyajit Ray, 1955) ● Pickpocket (Robert Bresson, 1959) ● The Pirates of the Caribbean: The Curse of the Black Pearl (Gore Verbinski, 2003) ● Point Blank (John Boorman, 1967) ● Psycho (Alfred Hitchcock, 1960) ● Pulse (Kiyoshi Kurosawa, 2001) ● Pumpkinhead (Stan Winston, 1988) ● Red Beard (Akira Kurosawa, 1965) ● Rope (Alfred Hitchcock, 1948) ● Rumble in the Bronx (Stanley Tong, 1995) ● The Salesman (Asghar Farhadi, 2015) ● Scotland, PA (Billy Morrissette, 2001) ● The Servant (Joseph Losey, 1963) ● The Seventh Seal (Ingmar Bergman, 1957) ● Sex, Lies, and Videotape (Steven Soderbergh, 1989) ● Silent Light (Carlos Reygadas, 2007) ● Single White Female (Barbet Schroeder, 1992) ● Solaris (Andrei Tarkovsky, 1972) ● Some Kind of Wonderful (Howard Deutch, 1987) ● Star Trek (J.J. Abrams, 2009) ● Still Walking (Hirokazu Kore-eda, 2008) ● Stranger Than Paradise (Jim Jarmusch, 1984) ● Stray Dog (Akira Kurosawa, 1949) ● Stranger Than Fiction (Marc Forster, 2006) ● Strictly Ballroom (Baz Luhrmann, 1992) ● The Swimmer (Frank Perry, 1968) ● T2 Trainspotting (Danny Boyle, 2017) ● The Testament of Dr. Mabuse (Fritz Lang, 1933) ● Theater of Blood (Douglas Hickox, 1973) ● They Live (John Carpenter, 1988) ● Thief (Michael Mann, 1981) ● Trainspotting (Danny Boyle, 1996) ● Tropical Malady (Apichatpong Weerasethakul, 2004) ● The Umbrellas of Cherbourg (Jacques Demy, 1964) ● Uncle Boonmee Who Can Recall His Past Lives (Apichatpong Weerasethakul, 2010) ● Viridiana (Luis Buñuel, 1961) ● Walden (Jonas Mekas, 1969) ● The Wayward Cloud (Tsai Ming-liang, 2005) ● While You Were Sleeping (Jon Turteltaub, 1995) ● White Dog (Samuel Fuller, 1982) ● Z (Costa-Gavras, 1969)

What a great list. It will help me figure out what to watch when I am like “omg what should I watch tonight.” Thanks! So thoughtful.

Delighted to see Sweet Smell of Success and Black Narcissus here. There might – might! – be better movies in history, but my god, those are such concentrated doses of cinematic pleasure.

Not one film by the Jean’s, Renoir or Cocteau?! But the first Star Trek, not even Wrath of Khan? Très Absurde! The Trylon volunteers must be doing too many gummies.