| MH Rowe |

WALL-E plays at the Trylon Cinema from Friday, January 20 through Sunday, January 22. Visit trylon.org for tickets and more information.

Is WALL-E (2008), the dystopian frolic of a film celebrated for its cleverly desolated planet Earth, its jokes aimed at adults, and its lonely robot protagonist, really a movie for kids? Of course it is. There’s the all-ages slapstick for one thing.

Our titular hero, WALL-E, has a job on Earth sorting junk (this movie is full of junk, not quite ruins) after all the humans have gone away. He is a Waste Allocation Load Lifter—Earth Class. During our introduction to the character—twenty minutes that are all imagery, little dialogue—he sorts, compacts, and organizes the junk while pulling a Looney Tunes impression. He chirps in dismay while accidentally bashing himself in the face with a paddle ball. He mutters a stunned “whoa!” after donning a bra like goggles. In an especially good gag, he loses a wrestling match with a vigorous fire extinguisher.

The film also revels in the joys of animation. Just past the midway point, WALL-E twists and soars through outer space with bumbling and then acrobatic delight by using a fire extinguisher as a rocket—his second and more successful encounter with this tool of public safety. Or consider the scenes where EVE, an Extraterrestrial Vegetation Evaluator and the object of WALL-E’s affection, arrives on Earth looking for plant life and twirls and zooms around the mounds of garbage, like a wireless mouse that’s learned to dance. She’s the first “new” thing WALL-E has ever seen. For all their animated glory, these and other scenes also ape the camerawork of live action, playing with depth of field and bringing backgrounds in and out of focus.1 When I rewatched WALL-E with my nephew at Christmas he cackled at some of the slapstick and sat rapt at those soaring scenes. So, yes: kids movie.

But is WALL-E so dystopian? That answer, I think, is no, despite its reputation. What makes the real difference between dystopian and not is Hello, Dolly!, the 1969 musical that inspired part of film’s plot.2 WALL-E opens with the musical’s “Put On Your Sunday Clothes,” which features lyrics WALL-E might sing himself, if he could sing:

Out there

There’s a world outside of Yonkers

Way out there beyond this hick town, Barnaby

There’s a slick town, Barnaby

This is WALL-E to a T. The film plays him not as sophisticate but a bumpkin, a day laborer with his lunch cooler who lives way out in this hick town wearing broken shoes (he has to salvage new treads from a defunct robot who looks just like him). He spends his days cooing over junk he adores, like a lighter and the box a diamond ring comes in. Meanwhile he yearns for what’s elsewhere, that is, in the city. Gazing at the stars through a part in the clouds, he plays back the lyrics from “It Only Takes a Moment,” another tune in Hello, Dolly!:

And we’ll recall when time runs out

That it only took a moment

To be loved a whole life long

In Hello, Dolly!, two new lovers sing these words after meeting in New York. When WALL-E looks up, while the song plays on the recording device built into his chest, he senses a promise that is both cosmic and cosmopolitan.

So the plot of WALL-E is the stuff of urban romance. It begins in the country and commutes to the city, where EVE returns when she discovers the plant sample WALL-E found, and finally circles back to his hick town wasteland to re-people the world. WALL-E plays his part by sneaking aboard EVE’s citybound ship. He imagines the cosmopolitan life, literally cosmic in this case, and wants to be with EVE, to preserve the junky little plant because that’s what EVE needs. It’s her directive, so it’s WALL-E’s directive too.

Out there really is a shining city. This slick town, which sent EVE out as a probe, is also a spaceship called Axiom, and it has housed human beings for 700 years, far longer than its original corporate mission. It’s not a starship built to save or preserve but an automated, full-service lifeboat meant to help its passengers wait out the cleanup project back on Earth—a lifeboat, resort, and mall food court wrapped into one. No one walks. They use floating chairs.

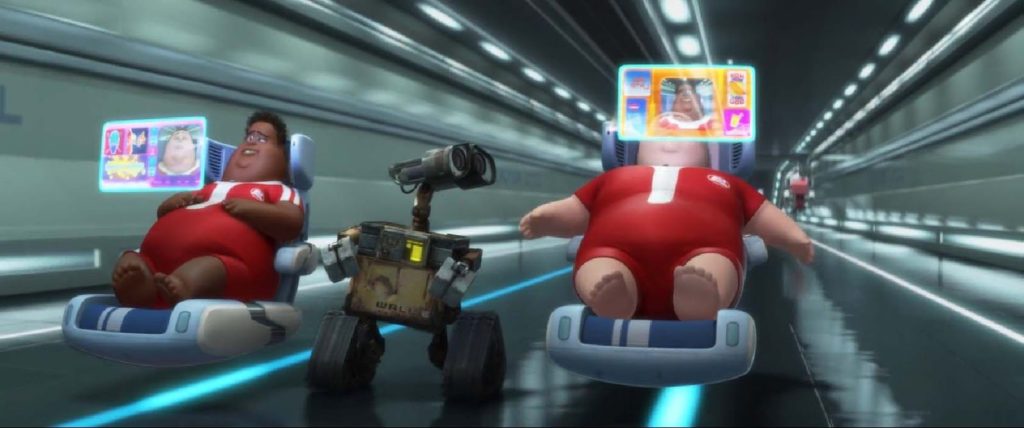

Axiom constitutes a highly administered metropolis as well. Humans on the ship have grown cartoonishly large over the course of centuries. They spend their time sucking down milkshakes and gossiping over video chat while monitored by a succession of captains and AUTO, a security apparatus and autopilot carrying out its final orders: Do not return to Earth as originally planned.

The largeness of Axiom’s passengers represents one of WALL-E’s missteps. Coupled with the fact that their wheelchair-like vehicles are equated with a sort of prison, their appearance implies that fatness is an embarrassment. Not that the filmmakers expend much effort to make them fully realized characters. Still, the film uses flesh-and-blood actors to portray long-gone corporate overlords, who created Earth’s junk and its totalitarian lifeboats. You’d think the filmmakers could have explored the idea of evolving into cartoons as a sign of lost resolution. Despite their size, the humans are thinly imagined in WALL-E.

Though the second half of the film is weaker than the first, one scene on Axiom explains its entire moral universe. When WALL-E arrives on the ship, an automated scan discovers how filthy this little robot is. He’s covered in the honest results of his labor. An even smaller robot named M-O, or Microbe Obliterator, flips out at WALL-E’s level of filth. In fact, M-O so obsessively carries out its programming—to eliminate “foreign contaminants”—that the bugger abandons its post. That is, all the robots onboard Axiom and even the humans in their floating chairs navigate the vast ship by following precise lines that dictate where they go. These lines appear as illuminated strips of white, green, red, etc. M-O proceeds to clean up in WALL-E’s wake until the crumbled trail of dirt veers off M-O’s assigned path. M-O stops and anxiously examines the deviation. With visible fear and trembling (you can almost picture the god M-O dreads), the filth-obsessed robot jumps off the path and forges a new one, pursuing its “directive” at the expense of any prescribed traffic lane. Desire and independence, maybe even freedom, burst out within the confines of obedience. Obedience becomes choice. Task becomes passion. M-O has changed forever while remaining sort of exactly the same.

Same goes for WALL-E, EVE, and AUTO, who resorts to eventually tiresome deceptions to prevent humans from returning to Earth. WALL-E’s years of sorting have led from obsession to love. EVE begins as a cop looking for plants; she shoots first and asks questions later. In her frustration she takes out entire rusting ships, but when she softens, she violates as many rules as WALL-E out of a dedication to her directive that mixes defiance and commitment. For Auto, too, commitment and defiance drive his actions. The result is hectic business in the film’s final third. WALL-E gets banged up, but as Walter Matthau grouses in Hello, Dolly!, “Any man who goes to a big city deserves what happens to him.” No matter. Constraint makes robot and human alike pursue their directives with even more vigor, to the point of self-expression, however slightly deranged. A little bit of derangement is a sign of moral independence.

The film has another beguiling fantasy to sell us, too. It’s the idea that people accustomed to life on Axiom would give it up. Not that they have much of a choice. The film favors the quasi-military authority of Axiom’s captain over the automated (and AUTO-assisted) corporate policies keeping the ship away from home. But the captain’s choice is more powerful than administration. After all, he can make the afternoon morning again by turning a dial in his control station. When he reads about dirt and hoedowns, he decides that all humans have to go back to Earth. His fellow passengers, meanwhile, don’t even realize the amenities aboard Axiom. One of them has to get knocked off course and ejected from her chair to realize there’s a swimming pool, which presumably has been there for 700 years. Unlike M-O, Axiom’s human passengers have to be pushed to find a more passionate commitment, in this case a dedication to the idea of rooting around in the dirt, building things, dancing, living a planetary life. Their captain decides for them anyway, but the film doesn’t linger on possible objections.

If derangement is the sign of an independent creature in WALL-E, it touches everyone in the film. M-O and EVE get deranged by doubling down on their directives. WALL-E, too. Even AUTO. At the end, the humans have to get unstable as well and happily return to an Earth where they might be unable to live. They abandon one discipline for another (digging in the soil, growing their own food). Maybe there is no suitable place but only stewardship on this junk-filled planet. As Morpheus tells Neo in The Matrix, “Welcome to the desert of the real.” Come back to the wasteland, WALL-E adds—it’s where you belong.

NOTES

1 Bill Desowitz, “Hello, ‘WALL-E’!: Pixar Reaches for the Stars,” Animation World Network, June 27, 2008, https://www.awn.com/animationworld/hello-wall-e-pixar-reaches-stars

2 Maureen Lee Lenker, “WALL-E Turns 10: Andrew Stanton explains the film’s Hello, Dolly connection, Entertainment Weekly, June 27, 2018, https://ew.com/movies/2018/06/27/wall-e-anniversary-andrew-stanton-hello-dolly/

Edited by Matt Levine