| Finn Odum |

Stardust plays at the Trylon Cinema from Friday, April 28 through Sunday, April 30. Visit trylon.org for tickets and more information.

Minor spoilers for the film Stardust included.

Since the dawn of time—which began either in a rural Tennessee farmhouse or a rented duplex in Milwaukee—I have been a movie person. My early childhood memories overlap with scenes from A Bug’s Life, A Night at the Opera, and Air Bud. Some of the fondest moments of my youth were the Friday nights we spent as a family watching a movie—locked in time, sharing a cinematic experience for the first (or second or fifth) time. We watched old classics, movies my parents loved, and poorly animated cash grabs for children. I probably owe my parents some therapy for the number of times they had to watch Anne Hathaway’s Hoodwinked. In any case, although I didn’t consciously center my personality around film, it was a core tenant of my grubby little seven to eight-year-old identity. Movies were my window to the rest of the world.

Our household was big on fantasy films. We loved The Princess Bride, obviously, but also Bedknobs and Broomsticks, The Chronicles of Narnia, and Ella Enchanted. Fantasy films expanded the horizon of storytelling; the rules of reality were different. In between the Christian allegories and the tween literary adaptations were stories about marginalized communities winning their freedom, women fighting for their autonomy, and families finding each other. Fantasy stories were about identity, youth, and free will, each one of them unique and vibrant.

So oh my god, why can’t I remember ever watching Stardust?

You have to understand, my parents both love this movie. I confirmed it before I started this essay. My mother claims to have watched it multiple times, but I can’t remember it at all. For years, I held onto the memory of a strange little movie with a unicorn as a side character. I recall a fondness for the film, but little else. When the Trylon’s programming schedule was released, I was thrilled to revisit this hidden gem from when I was a kid. But after watching it for this essay, I don’t know if I’ve ever seen it before.

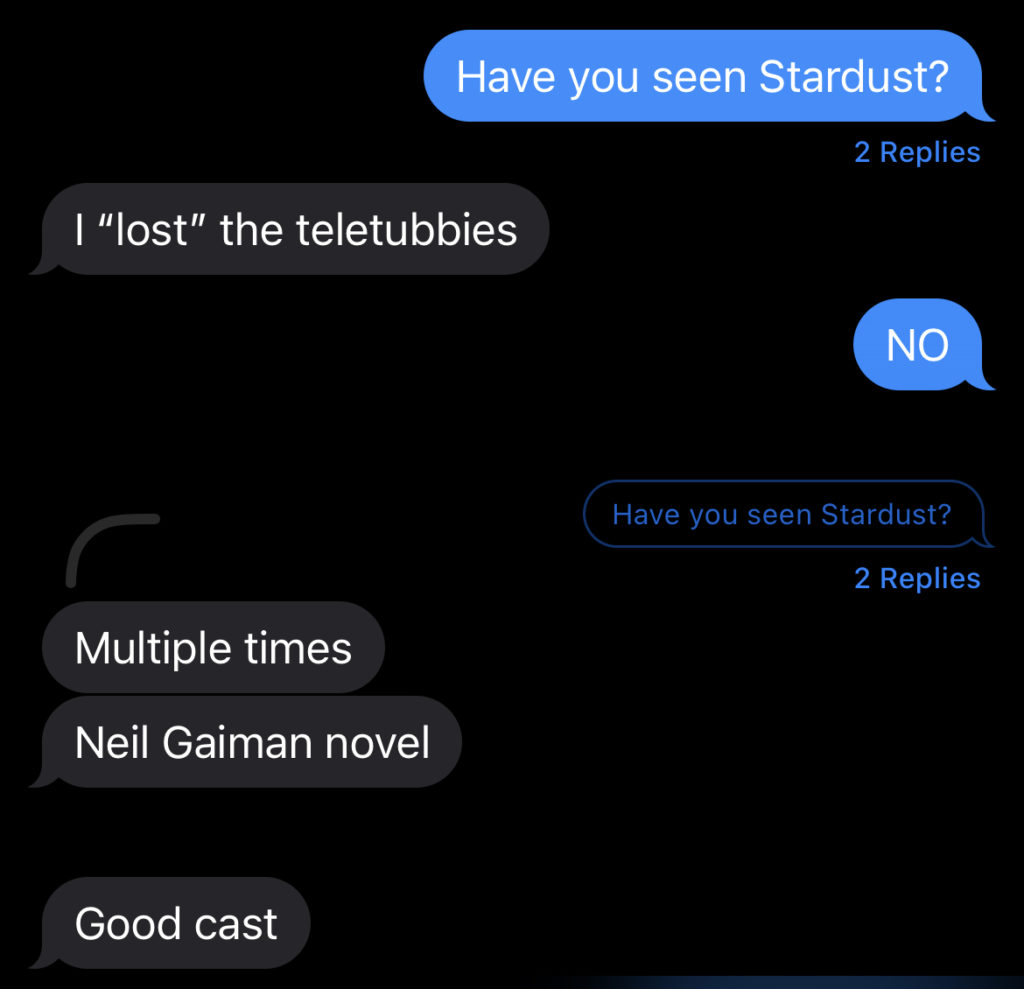

Pictured: my parents confirming in text messages that they both love Stardust, as well as my mother admitting she threw out my Teletubbies VHS tapes.

Revisiting my childhood and Stardust simultaneously feels serendipitous, given the film’s central themes of youth and aging. It’s a whimsical reimaging of Neil Gaiman’s much darker novel, which itself is an adaptation of a DC Comics mini-series. Compared by Gaiman himself to It Happened One Night, Stardust is both a romance movie and a coming-of-age story. It follows Tristan (played by an adorable pre-Daredevil Charlie Cox) as he attempts to capture a star so he can win over village girl Victoria (Sienna Miller). On his journey, he encounters the star’s corporeal form Yvaine (Claire Danes), who, unbeknownst to either of them, is being hunted by the witch Lamia (our lord and savior Michelle Pfeiffer) and Prince Septimus (our other lord and savior Mark Strong). While Septimus is seeking out the star so he can retrieve a ruby and take control of the kingdom, Lamia has a much darker intent: eat Yvaine’s heart and gain eternal youth.

There is tension between Tristan’s growing up story and Lamia’s desire to regain her youth. The witch believes her power is rooted in being young and not in the wisdom she’s gained while aging. Nor is it rooted in the connection she has with her sisters; they do not value each other, just the magic they possess and the promise of becoming beautiful again. They argue frequently throughout the film, and eventually, all die in their vain quest to become young again. Tristan, on the other hand, grows more confident as he embarks on his perilous journey. As he grows into himself, Tristan discovers the importance of love and family. He learns to stand up for himself, figuratively and literally, and while Lamia cannot accept growing old, Tristian learns to embrace it by the end of the film.

Stardust does a great job of depicting themes like aging through a childlike lens—a skill I attribute to both its genre and the mastermind behind the story (not only Gaiman, but also director Matthew Vaughn). The fantasy genre provides creators with an opportunity to break down difficult ideas into magical, easy-to-understand stories for younger audiences. In contrast to its rather graphic source material, the Stardust film treats the darker parts of the story with levity and whimsy. Not only does that effort make the film more family-friendly; it helps break down difficult concepts like aging and death. The subplot about Septimus and his fratricidal brothers is lightened by their ghosts, who are eternally stuck in whatever form they were killed in (including the brother who’s half-flattened after being pushed out a window). Death is not gruesome; instead, it is made into something lighthearted and easier for a child to understand. Similarly, the film ends with Tristan and Yvaine ascending to the sky to become stars. There is magic and beauty in their metaphorical passing.

Outside of its handling of tough concepts, Stardust is a movie built on childhood wonder. In between the main conflict and character desires is a world of imagination: a fantastical realm where royals have blue blood and candles can fly you skyward, witches can turn you into small mammals, and kings can knock a star out of the sky with a pendant. England’s considered fiction. There’s a unicorn. Stardust looks at the world the way a child would, all while addressing the importance of growing up.

Given how much Stardust has in common with the other fantasy films I watched as a kid, I’m choosing to believe that it really is the unicorn movie of my memories. Even if I didn’t relive the wonder of watching it when I was younger, there’s a certain magic in experiencing that kind of childhood whimsy. For a moment, I was living in that world, flying on an airborne pirate ship alongside the main characters. I look forward to revisiting it again—maybe when I’m older and well on my way to ascending to the stars.

Edited by Olga Tchepikova-Treon

They were LOST. LOST, I tell you.