| Lucas Hardwick |

The Thing from Another World plays at the Trylon Cinema from Friday, July 7 through Sunday, July 9. Visit trylon.org for tickets and more information.

**Warning: this article contains minor spoilers.**

The radical conservative is capable of some of the best science-fiction known to mankind. The evidence has never been clearer than in the wake of the Trump administration and the recent COVID pandemic that saw people avoiding the Coronavirus vaccines for fear of being injected with microchips that would track their trips to Walmart or church or the Speedway.

Radical Trump supporters who swore allegiance to the mysterious QAnon movement envisioned the president winning a second term only to relinquish his power to a newly resurrected John F. Kennedy, Jr. poised to save the nation from godless liberal politicians who eat babies and worship Satan in the basements of Washington, D.C. pizza parlors. Lest we forget the radical right-wingers who sought to expose President Barack Obama and his administration as a gang of lizard-headed shapeshifters. If these instances of bizarre, politically charged dogma weren’t so terrifyingly true, they would be some of the finest science-fiction stories ever written.

With advances in A.I. and a liberal administration that’s toying with the idea of digital currency, I for one can’t wait to see what next-level Phillip K. Dick business these rascals come up with. But there was a time when conservative paranoia rallied around a cause everyone could get behind in the form of ousting good old fashioned fifth column communist infiltrators. The folksy charm of the Second Red Scare after World War II not only got people cross-examining their neighbors and co-workers, but allegorically influenced film and television through genre storytelling, specifically science-fiction.

Sci-fi films of the 1950s were rife with metaphors that regularly replaced the fear of burgeoning Bolsheviks hiding in plain sight with catastrophic alien invasions. And with a nation still high on dragging the European Allies through back-to-back World Wars, these movies often portrayed an arsenal-addled military with an itchy trigger finger that sure as hell wasn’t about to put up with anything that wasn’t, by God, American, and was more than happy to obliterate trespassers from anywhere that wasn’t planet Earth.

Movies like George Pal’s War of the Worlds (1953) and William Menzies’ Invaders from Mars (1953) were obvious parables of the destruction associated with a communist incursion. Don Siegel’s Invasion of the Body Snatchers (1956) was more subtly about Soviet infiltration using alien-bred soulless doppelgängers to parallel friendly neighborhood comrades who had quietly defected. And Robert Wise’s The Day the Earth Stood Still (1951) was a call for peace at the promise of global annihilation from neutral-minded extra-terrestrials suggesting that everyone shape up lest we all suffer hubristic elimination.

As McCarthyism swept the nation, ousting pinkos everywhere (including at the highest levels of government) and blacklisting a significant portion of Hollywood socialists, the movie industry was wise to present nothing but 100% Made In the USA entertainment. Whatever the might of the military might be in these films, and whether the message be for peace or destruction, the ominous threat of the big red menace still hung in the air.

It’s important to remember that during this time, not only was the Second Red Scare in full swing—and would last until around 1957—but the United States, fresh off its annihilating victory in the Pacific Theatre, was in the midst of occupying South Korea after rooting out the Japanese in an attempt to unify the nation with its Soviet-occupied northern neighbor.

In June of 1950, North Korea would invade the South, hurtling the U.S. right smack into the middle of a brand spanking new war only five years after the end of World War II. And this time, instead of stifling a genocidal tyrant, the mission would be to preserve the great institution of democracy that the Allied powers had worked to establish in every corner of the globe since, oh, the beginning of time.

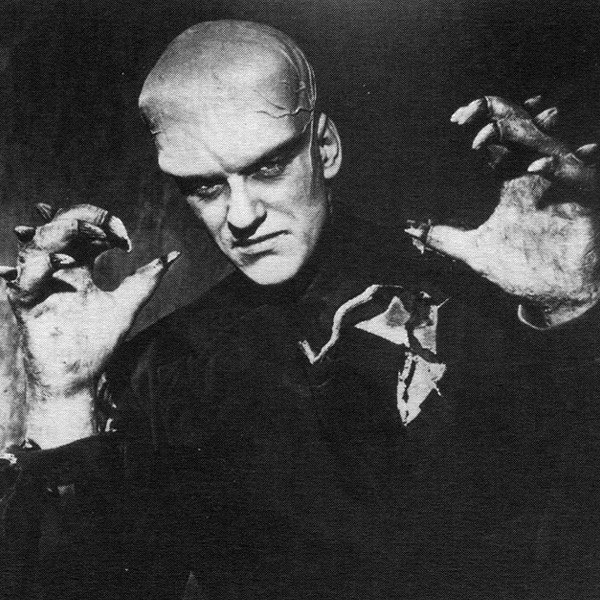

Promotional still featuring James Arness as “The Thing.”

Meanwhile, back in Hollywood and Glacier National Park, producer Howard Hawks, director Christian Nyby, and screenwriter Charles Lederer would be working on the now-classic sci-fi horror film The Thing From Another World. It’s the time-honored tale of finding something weird frozen in the ice and the dangers of having a closer look. A team of scientists near the North Pole locate what they believe is a large aircraft frozen beneath the surface, so they call up the nearest Air Force base to check it out. Once Captain Patrick Hendry (Kenneth Tobey) and his squad arrive they can’t wait to plant a few thermite bombs and crack this puppy open. In the process, the bombs react with the mysterious metal of the craft, destroying the vessel but also revealing what the gang believes to be the ship’s pilot trapped in ice near the ship.

Determining that the craft and its jockey are not of this earth, the team hauls the Thing from Another World back to their base, encased in a block of ice. While standing watch over the creature during the night, a heedless airman with an electric blanket soon becomes responsible for unleashing the frozen hell whose single-minded mission is draining the blood out of every living thing it can get its plant-based paws on. Sure, it’s the definitive yarn of an alien hellbent on exterminating the human race, but it’s also the story of an America ready to take action against a world of communists breathing down its neck.

Frozen hell awaits Captain Hendry’s squad.

Once the monster breaks loose and commences with the bloodletting and once lead scientist Dr. Carrington (Robert Cornthwaite) determines that the creature is basically an overgrown carrot that requires human blood to persist, the group ideology of what to do about the Thing splits. Dr. Carrington hopes to preserve the monster to study and communicate with it. Captain Hendry and his crew just want to blast the lumbering beast into Kingdom Come. Kind of funny how Dr. Carrington speaks in a British accent, isn’t it? As in, he’s not American, for anyone still not on board with the whole “democracy or bust” message in this film. Even Carrington’s American secretary, Nikki Nickelson (Margaret Sheridan) defects from his charge and sides with Captain Hendry. Of course, a little sexual tension never hurts for choosing to side with the free world.

Hendry and his crew are pretty confident in their assault on the Thing, quickly surmising that fire is likely the only thing that will stop the monster, until it doesn’t. It’s important to take a moment to pause here and note that this film contains one of my all-time personal favorite on-screen attacks: the legendary man on fire.

But fire doesn’t stop the Thing, and from this point, a palpable fear permeates the film as Hendry’s gang formulates a plan B to quell the spread of communism…er, I mean, hostile alien takeover. Fear in the face of an unstoppable force places our heroes in a rather humble position after being so eager to blow everything up. In fact, it’s a bit surprising that Hendry and his team would even take a moment to flinch in the face of a misstep like not being able to destroy an alien bloodsucker with as brutal a tactic as blazing inferno.

One bit of triggering dialogue with regard to America’s might keeps anyone from being too modest for too long though. Dr. Carrington attempts to appeal to Hendry’s men with a more thoughtful approach to sacrificing themselves for the sake of science, stating that “it doesn’t matter what happens to us. Nothing counts except for our thinking. We thought our way into nature. We split the atom.” Hendry’s subordinate, Lieutenant Eddie Dykes (James Young) unironically smiles and responds rather smugly, “Yes, and that sure made the world happy, didn’t it?” Yowza! Too soon, bruh. Doc Carrington walked right into that one.

The mission to preserve democracy comes from a good place in the midst of a crimson-hued context, but the military’s—a.k.a. America’s—“fuck science” stance in this film doesn’t age well in a modern setting. Ironically, and whether Hendry and company realize it or not, the gang is forced to resign itself to science to eventually still the beast. And what fire alone couldn’t accomplish, barbed-wire weaponized with a gajillion volts of electricity makes short work of eliminating the alien plague that threatens the sovereign world.

The self-effacing notion of science for the sake of humanity struggles in the face of the perception and elimination of all threats, portraying Dr. Carrington as almost villainous next to Hendry’s Heroes who could care less about learning anything from the monster. Carrington even sports a nefarious appearance with a pointed goatee, black coat, and prissy, devilish British accent. If it wasn’t for the Thing, Carrington would most certainly be the villain. His motives, however, can be rationalized, they just happen to not align with the greater American cause that the film preaches.

Hendry’s heroes.

Squint your eyes and Carrington and the Thing would be a diabolical mad science dream team evocative of the Universal horror films of the 1930s. Without squinting, however, Carrington evokes sort of a handsome progressive sociology professor vibe; not a villain, but an obnoxiously antagonistic know-it-all who might steal your girlfriend.

What really sets The Thing From Another World apart from the comparatively silly genre flicks that came before is that this film enlists real science to stake its narrative claim in the midst of a profound political context. Sure, the Thing is a mutant creepozoid from another planet, but the film uses actual science to help us understand exactly what he is. He’s a walking vegetable that survives on human blood.

But why do we need to understand more about the Thing other than its relentless pursuit of death to the human race? Because while our supremely leftist opposition in the global theater also seeks to consume every free nation in the world, it too is poised to survive at all costs, up to and including defecting our own people to its cause. By understanding the Thing, it becomes a more precise enemy that becomes easier to relinquish. Communism isn’t just a red shapeless mass that simply destroys everything in its wake; it’s an institution with specific intentions, and it’s only a monster because it doesn’t jive with our nation’s political position. What this film tells us, besides that our enemies are out to destroy us, is the importance of understanding them in order to destroy them more precisely.

Vegetable man or Commie red?

In John W. Campbell’s Who Goes There?, the novella that The Thing From Another World is based on, the story takes place in Antarctica and features a monster capable of taking on the shape and identity of anything it infects, imbuing the tale with a sense of chilling isolation and heart-pounding paranoia. The story was first published in a 1938 issue of Astounding Science Fiction magazine, and was undoubtedly written with an entirely different social context in mind. This is precisely why Hawks’ adaptation takes place in the North Pole and why the Air Force’s Alaskan Air Command is summoned: If the Russians are coming, it’ll be by way of our Canadian neighbors. To quote former Alaskan Governor—and conservative—Sarah Palin, “I can see Russia from my house.” And instead of Russians, Hawks’ film establishes the next best threat in this geographically convenient setting: a non-communicative vegetable man from Planet X that can regrow limbs and hatch pod-people with the same hive-minded intentions for global domination; a.k.a. godless communists.

You’re probably saying, “Lucas, you sound as loony as those conservative radicals you were talking about six hours ago when I started reading this article.” Maybe. But the neatest thing about The Thing From Another World is the subtle angle that the entire story is predicated on: newspaper reporter Ned Scott (Douglas Spencer) looking for a story. Throughout the film, Scott is permitted the fullest extent to record and recount the horrific events that unfold, and never once is he stifled or insulted by Hendry or his men. This profound expression in favor of the fourth estate is arguably the most important message in the movie.

In the film’s final moments, as Scott files his report via radio back to a group of journalists in Anchorage, his charge to all reading and listening is to “Tell everyone wherever they are. Keep watching the skies.” Watch the skies indeed—not only for vegetable men from Mars, but for the imminent threat to the inherent freedoms that bring you this message.

Edited by Olga Tchepikova-Treon

I disagree that Carrington’s idea can be rationalized and that Hendry’s plan is an example of “fuck science.” What if Carrington had his way? What if they all died to preserve the alien, and he killed them all, and then killed the next group to investigate, and the next, meanwhile growing others of its race? What is learned by man and science? Only death.

Hendry realizes this and know the only course is self-preservation, and uses science to defeat the creature, not ironically, but just good ol’ American know-how.