| Jay Ditzer |

Super Fly plays at the Trylon Cinema from Friday, July 14th, through Sunday, July 16th. Visit trylon.org for tickets and more information.

Where would movies be without music? Even in the silent era, movie theaters had a pianist on hand to provide accompaniment. Since the advent of “talking pictures,” music of some sort—whether it be a full score or contemporary tracks either licensed or custom-written—is almost always present in movies (there are, of course, movies without any music; No Country for Old Men and The Birds spring to mind). The absence of music in both of these movies subtly increased the tension and feelings of dread. Subliminally or otherwise, that absence of music tells you that something is off—so ingrained is the notion that movies have music).

There was an internet trend a few (checks notes) 15+ years ago in which people would take scenes from a movie and replace its original musical cues with other songs, completely changing the genre of the movie. For example, rejiggering scenes from The Shining, underscoring it with (what else?) Peter Gabriel’s “Solsbury Hill” and voilà: a trailer for Shining, a feel-good romcom from Stanley Kubrick (watch it here). Or re-editing clips from Willy Wonka and the Chocolate Factory with a creepy, ominous soundtrack to turn it into a horror movie (although a lot of people who first saw Willy Wonka as children already think it’s a horror movie—Trylon’s long-time volunteer Dave Berglund can attest to this, if you ever caught his Introduction slide playing during the trailer show).

All of this is to say that when a movie has the right tone and the right music, it can be transcendently synergistic: the movie elevates the soundtrack and the soundtrack elevates the movie in a Moebius strip of excellence. But then again, while a movie is diminished without its soundtrack, you can usually listen to the soundtrack on its own, for its own sake.

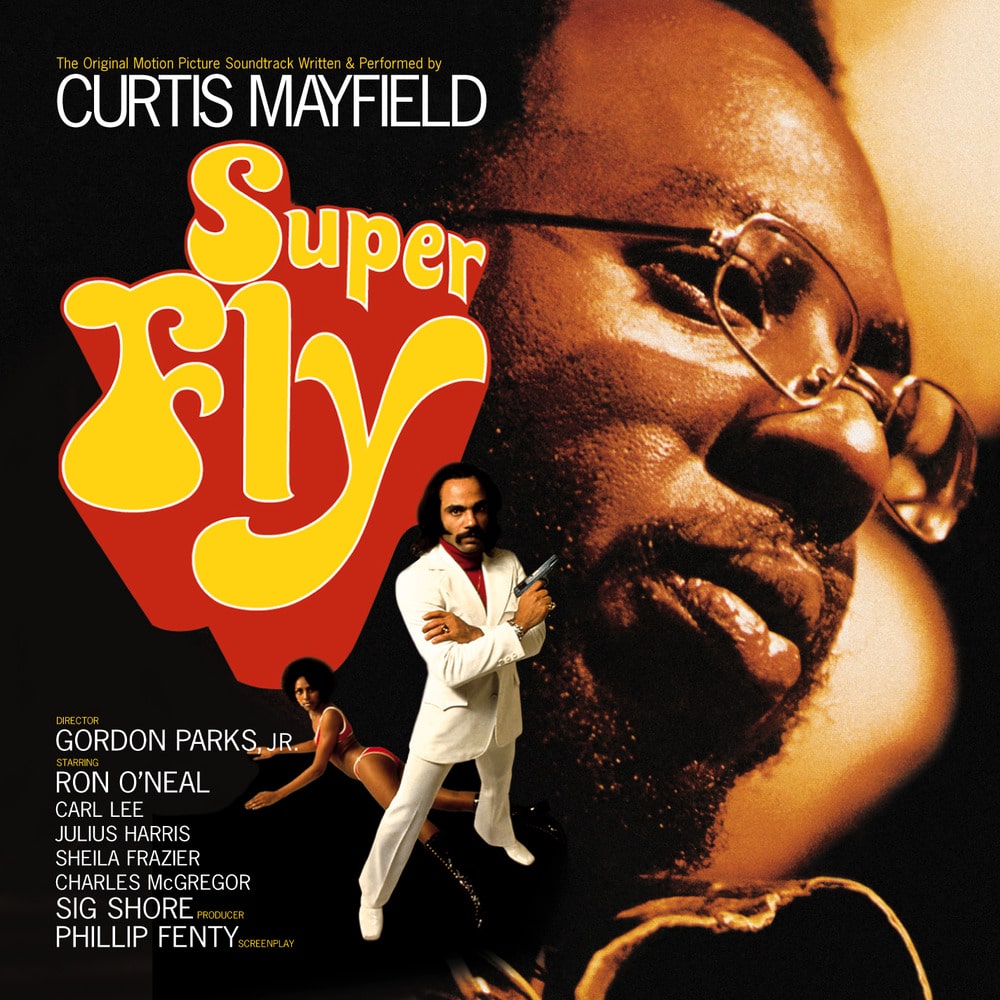

Case in point: Curtis Mayfield’s Super Fly. One of those rare soundtracks that was more commercially successful than its corresponding film (see also: Saturday Night Fever, Footloose, Singles), the Super Fly soundtrack album nowadays can easily feel like a concept album that has an accompanying film as much as the other way around.

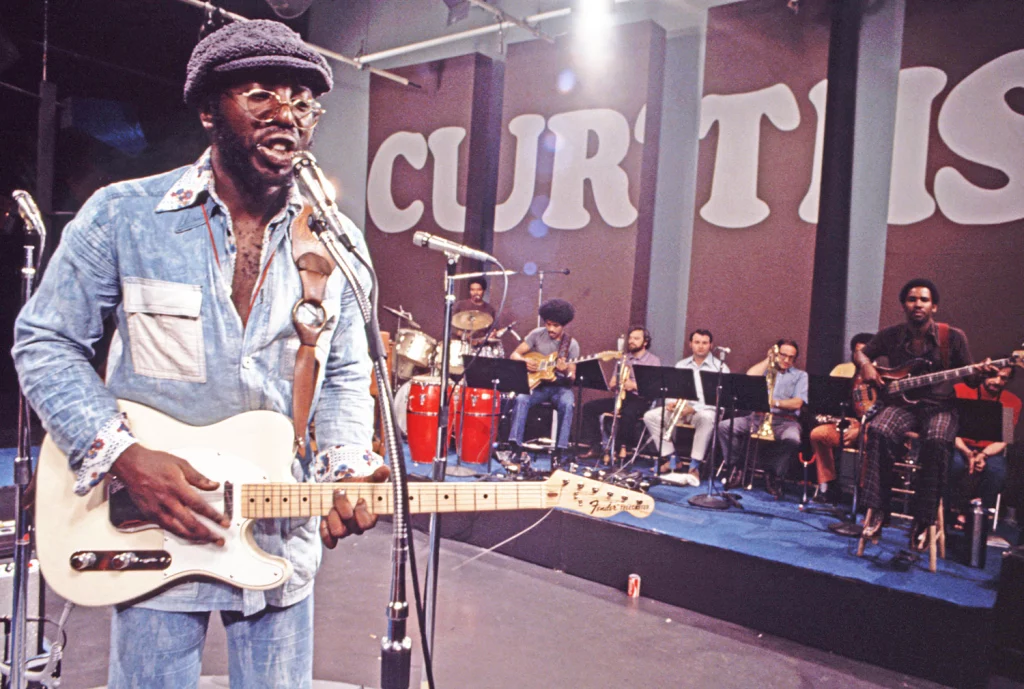

Curtis Mayfield was the guitarist, main songwriter, and occasional lead singer of the R&B group The Impressions. In 1970, he embarked on a solo career. His debut album, Curtis, serves as a kind of signpost for the material Mayfield would spend the next decade creating. Indeed, its eight-minute opening track “(Don’t Worry) If There’s a Hell Below, We’re All Gonna Go” is like a theological blaxploitation soundtrack in miniature, opening with fuzz bass cross-faded with a spoken-word section in which a woman discusses the Book of Revelation. Skittering bongos and percussion join in as Mayfield assures “sisters, n*****s, whiteys, Jews, crackers” that if there is an underworld in which blasphemous souls are punished, well, see you there. Then he screams.

The lyrics to “Hell Below,” sung by Mayfield in his sweet falsetto register, castigate the police, politicians, the legal system, and the military-industrial complex as well as drug dealers, the educational system, and oh yeah, Richard Nixon, as orchestrated R&B plays. It’s a complex, heady stew of horns, strings, wakka-chukka-wakka-chukka wah-wah guitars, grinding bass, and all the polished-yet-gritty accouterments that made soul music from the 1970s so amazing.

Meanwhile, cinema was undergoing its own little revolution with the rise of “blaxploitation” films. It’s not quite agreed upon what the first blaxploitation picture was—maybe Cotton Comes to Harlem, which came out in 1969—but the blaxploitation “Big Three,” its best, its baddest, its most iconic movies, would be Sweet Sweetback’s Baadasssss Song (1971), Shaft (1971), and of course, Super Fly (1972).

Fun Fact No. 1: Shaft (coming to the Trylon on August 4th!) was directed by Gordon Parks; Super Fly was directed by Gordon Parks Jr.

Each of the blaxploitation Big Three has a contemporary soundtrack performed by established or soon-to-be-established R&B acts. Crucially, all three films utilized those soundtracks as integral parts of their narratives. And while Isaac Hayes’ Shaft soundtrack is a solid hunk of vinyl, and “Theme from Shaft” features the classic “‘They say this cat Shaft is a baaaaad mother…’-‘SHUT YOUR MOUTH’” exchange, and he collected the Oscar for “Best Original Song” (the first Black musician to do so), for my money, Mayfield’s Super Fly is the alpha and omega of blaxploitation soundtracks.

The plot of Super Fly is pretty basic—drug dealer Youngblood Priest (Ron O’Neal) tries to go straight, the end. But Mayfield’s soundtrack is not just the icing on the cake; it’s like the flour or the eggs or the sugar. Super Fly wouldn’t be Super Fly without it.

Opening cut “Little Child Runnin’ Wild” sets the tone of the record: A funky organ riff gives way to nasty fuzz guitar and orchestral sweetening punctuated by horn stabs. Jazzy sax fills trade melodic lines with Mayfield’s vocals. Its lyrics serve as a biography of those victimized by the drug trade: “Don’t care now what nobody say / I got to take the pain away / It’s getting worser day by day / And all my life has been this way.” These lyrics, of course, aren’t just specific to the storyline of Super Fly but speak to the lives of many people in America then (and now). Elegiac strings underscore the pathos and take us to the fade.

“Pusherman” is where the soundtrack really takes off. The song, which has a more stripped-down sound than many of the other songs, starts with tuned percussion and an ominous groove before Mayfield’s sparse guitar chords hint to where the melody will go. The song’s lyrics present a dilemma: the pusherman’s life sounds pretty sweet (“Secret stash, heavy bread / Baddest bitches in the bed”) but Mayfield’s obvious disdain for “the game” becomes apparent as the song unfolds (“Got a woman I love desperately / Wanna give her somethin’ better than me / Been told I can’t be nothin’ else / Just a hustler in spite of myself”).

In the movie, the song syncs perfectly with a scene in which Priest drives his customized Cadillac Eldorado through Harlem as various emergency vehicles pass him on the street, the sounds of their sirens fading just as the lyrics kick in. And surprise, it turns out the non-diegetic “Pusherman” used at the beginning of the scene is now diegetic in the club, where Mayfield is performing the song onstage. Maybe a little cheesy, but it’s still a neat transition.

Fun Fact No. 2: Mayfield hadn’t finished writing “Pusherman” when he agreed to appear in the film, so he put together a band (The Curtis Mayfield Experience), flew to New York from his home base in Chicago, and recorded the track the day before they shot the scene of the band performing it. Talk about tight deadlines.

Spoiler alert: Don’t get too attached to Fat Freddie. Another growling bass riff propels the song “Freddie’s Dead” and the insistent flute hook (which possibly maybe inspired the similar hook of Marilyn McCoo and Billy Davis Jr.’s 1976 pop hit “You Don’t Have to Be a Star, Baby”?) really gets under your skin before the dreaded key change kicks in.

It’s sometimes a challenge for composers who primarily write songs with lyrics to come up with compelling instrumentals; Mayfield had no such difficulties with “Junkie Chase,” an exciting bit of ‘70s R&B. Appropriately enough, “Junkie Chase” accompanies a scene in which Priest is robbed by junkies, and then chases them.

Fun Fact No. 3: As shown in film critic Elvis Mitchell’s great 2022 documentary Is That Black Enough for You?!?, while preparing to shoot the chase, O’Neal told director Parks he could jump a 5-foot fence during the chase and did just that in one take, which you see in the finished film.

Fun Fact No. 4: Gordon Parks Jr. was born in Minneapolis.

“Give Me Your Love (Love Song)” is, if the parenthetical “Love Song” didn’t inform you enough, the romantic interlude playing during the scene in which Priest and his ladyfriend enjoy a bubble bath (and other activities) together. The song is suitably warm and slinky and the lyrics express vulnerability: “You do what you have to do / I’ll share the weight / Whatever fate / Plans to bring to you.”

“No Thing on Me (Cocaine Song)” opens with a descending piano flourish that wouldn’t be out of place in a soap commercial. The polished sound and the upbeat major-key theme seem to be there to enhance Mayfield’s self-empowerment/anti-drug moralizing. Mayfield worried that Super Fly was “a cocaine infomercial” after viewing early rushes and tailored the lyrics as a sort of commentary about the pitfalls of the illegal drug trade and the dangers of glamorizing it.1

Priest’s backstabbing partner is the subject of “Eddie You Should Know Better.” One of the prettier songs on the record, “Eddie” is heavily orchestrated but the wah-wah guitar soloing in the left speaker keeps things contemporary. Mayfield’s lyrics (heck, even the title) have a weary, disappointed tone. At an economic 2 minutes and 20 seconds, the song says its piece and moves on.

“Think,” the album’s second instrumental, features gently strummed electric guitar augmented by bells (or is it a celeste?) giving way to smooth orchestration that veers dangerously close to easy listening territory, but Latin percussion and a heavy backbeat keep things on the right side of that line.

Album closer “Superfly” (the song formats “Superfly” as a single word; the movie title has it as two) is a sort of sister track to “Pusherman,” sharing distinctive instrumentation (e.g., more tuned drums), but this time the music celebrates our hero vs. chastising the generic drug dealer. “Superfly” the song emphasizes Priest’s intellect and abilities while still acknowledging the harsh realities of “ghetto life”; the key lyric (and another callback to “Pusherman”) is “Trying to get over / Trying to get over.”

The Super Fly soundtrack was a massive hit, topping the Billboard album chart and boasting two million-selling singles (“Freddie’s Dead” and “Superfly”) and as mentioned earlier, was a more successful album than Super Fly was a film (although the movie was a big hit as well). It was also the most commercially successful album of Mayfield’s lengthy career. More significantly, it was a cultural and critical success, earning four Grammy nominations in 1972.

Fun Fact No. 5: The Super Fly soundtrack was ineligible for Oscar nominations because self-taught musician Mayfield couldn’t read or write musical notation2 — a technicality that is straight-up hair-splitting bullshit on the part of the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences.

The legacy of Super Fly has been well-established as every song from the soundtrack has been covered or sampled by many prominent soul, rock, and hip-hop artists in the ensuing 51 years, five of which you can read about in Matthew Tchepikova-Treon’s just-out Perisphere piece. In 2019, the Library of Congress selected it for preservation in the National Recording Registry for being “culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant” (I’d say it qualifies as all three).

Bibliography

1 Burns, Peter, Curtis Mayfield: People Never Give Up, Sanctuary, 2003, as cited in “Curtis Mayfield’s ‘Super Fly’ Soundtrack: 10 Things You Didn’t Know” by Travis Atria Rolling Stone, July 11, 2022. https://www.rollingstone.com/music/music-features/curtis-mayfield-super-fly-things-you-didnt-know-1364038/

2 Burlingame, Jon, “The Grammy-Oscar connection,” Variety, Feb. 7, 2006. https://variety.com/2006/music/awards/the-grammy-oscar-connection-1117937593/

Edited by Olga Tchepikova-Treon