| Penny Folger |

The Night of the Generals plays at the Trylon Cinema from Sunday, July 30th, through Tuesday, August 1st. Visit trylon.org for tickets and more information.

Night of the Generals is a World War II film most people in this day and age have never heard of. It’s a joint production between the UK, France, and the United States. The story is unique in that it’s told from the German perspective, without demonizing them exactly: instead it throws a murder mystery on top of the war which it keeps as a backdrop. Murder, you say? But isn’t murder synonymous with war? It’s a question that comes up early in the film.

Asks Donald Pleasance’s General Kahlenberge of Omar Sharif’s Major Grau, who has been sent in to investigate the murder, “We live in an age in which bodies lie around the streets like cobblestones. What’s so unique about this case?”

It is odd that Major Grau seems more concerned with the casual murder of a prostitute (though she was also, as it turns out, a German agent) than with the carnage that surrounds them daily.

But, as Grau explains later in the film after a French inspector argues that all generals are, in fact, murderers, “What is admirable on the large scale is monstrous on the small.”

If you haven’t gathered yet, Generals is a war film that doesn’t focus so much on the actual war as it does on some of its participants. It’s a war film that, paradoxically, seems devoid of battle scenes (other than Peter O’Toole’s General Tanz going ballistic on a Polish ghetto in order to keep its citizens “in line”). It’s also subtly a satire—at least every time Pleasance as General Kahlenberge opens his mouth (reportedly, the 1962 best-selling novel by Hans Hellmut Kirst on which the film is based was even more blackly humorous in tone). Pleasance, always exquisite and comedically deadpan here playing a German general, ironically survived a real-life German prisoner-of-war camp during WWII.

Generals was the first time an American film received permission to film in Poland, though they had to change a few details, such as centering the story away from East Germany.

“From the Polish viewpoint to have the last chapters take place in East Germany would have offended a sister Communist country,” a spokesman at the time explained.1

This film has a rather sanitized view of the war as it’s nearing its final year (though the film’s timeline jumps around a bit). The few atrocities we do see serve mostly as a backdrop: aside from a brief scene where a couple is separated during a roundup of Polish citizens in the Warsaw ghetto.

Yet a minute later that same scene turns satirical. While Tanz’s men are rounding up the citizenry and one man from the herd tries to take a swing at them, we hear a Reich-appointed radio announcer narrate: “The population is extremely cooperative and friendly.”

What’s more surreal is that this commentator speaks in the voice of a 1960s radio announcer with an American accent. It turns out he’s a reference to Robert Henry Best, a U.S. foreign correspondent who later became a Nazi sympathizer and well-known broadcaster of Nazi propaganda on German radio. His presence here feels simultaneously satirical and menacing.

Satirical and menacing could just as easily describe O’Toole’s General Tanz. Tanz is a character from whom children in this movie literally back away on sight.

Much is made of such characters in the history of film—Anthony Hopkins in The Silence of the Lambs comes to mind (though I prefer Brian Cox’s more subtle, layered characterization of Lecter in Manhunter). Reviews dating as far back as General’s release are split on whether or not O’Toole here is brilliant and scene-stealing or one-note and over the top. In 1967 The LA Times seemed to agree about Tanz’s importance in the annals of history:

“Tanz—in the person of that extraordinary and fascinatingly unpredictable O’Toole—must go down as one of the most infamous figures in screen history.”2

Yet, Generals’ lack of commercial success sadly renders his character scarcely remembered.

Mixed reviews aside, one reason his character — and the film overall — might be lesser known is that it came along five years after its producer Sam Spiegel released his behemoth Lawrence of Arabia (Spiegel’s The Chase, which appeared between the two, received“a universal thumbs down” proving Lawrence was a tough act to follow).3

As essayist Scott Harrison put it, “Night of the Generals is a film that is damned by its own pedigree.”4

Generals’ director, Anatole Litvak, a prolific director of crime films in the ’30s and ‘40s had slowed his output in more recent years. Spiegel originally wanted Arabia’s David Lean for the job, who was unavailable. And Litvak owned the rights to the novel.

By 1972, Night of the Generals had lost at least three million dollars. Nevertheless, O’Toole, with the help of Pleasance, stole the film.

Newsweek said O’Toole’s General Tanz, “looks, with his remarkable facial tics, like a timebomb preparing to go off.”5

O’Toole’s characterization of Tanz feels like someone who’s looked up how to be a human being by taking a cursory glance through an instruction manual that’s missing some pages. His character was allegedly modeled in part on real-life SS officer Jürgen Stroop who led the suppression of the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising in 1943. But he’s also slightly reminiscent of Data in Star Trek: The Next Generation, in terms of the feeling you get that his character is attempting to replicate a human being and missing the mark slightly.

General Tanz: man, machine, or disgruntled cat?

Interestingly, O’Toole found himself wrong for the role, at least physically: “I have a modern face and there’s not a thing I can do about it,” said O’Toole in 1967. “I tried an expression. I tried a monocle. Nothing worked.”6

He eventually found a solution: after going to a British museum, O’Toole had his nose rebuilt with putty to resemble the image of an Etruscan warrior he had seen there.

At almost two and a half hours, this film goes many places, but at one point it veers slightly into the territory of adorable German sitcom material where the equally adorable Lance Corporal Hartmann (played by Tom Courtenay) desperately wants to rendezvous with his lover but is continually thwarted by having to babysit the terrifying Tanz.

This is in order to keep Tanz away from a plot that is brewing to assassinate Hitler (based on the real-life “20 July plot”). Ironically, the assassination of Hitler was a lifelong fantasy of O’Toole’s: one that he was later to gleefully act out in the 1976 British TV movie Rogue Male.

Said O’Toole in 1997, “It is impossible to write about me without mentioning Hitler.”7

During the aforementioned babysitting, as Hartmann chauffeurs Tanz across Paris, Tanz resembles a slightly bored cat sizing up the mouse that is Hartmann.

Babysitting has never been so awkward.

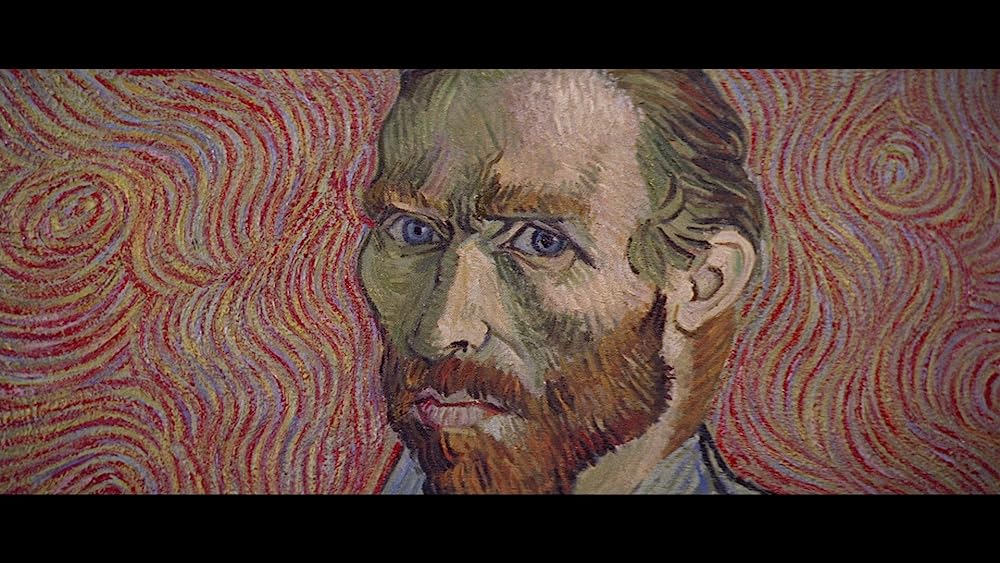

As they frequent a room for “decadent art” in a closed art museum, Tanz seems to go into an unhinged trance every time he views a portrait of Vincent Van Gogh. The movie is quick to point out that this portrait was painted by Van Gogh after he lost his mind.

These emotional outbursts are at first surprising considering there’s such a disconnect between Tanz and the rest of the human race—human emotion being a quality from which he is normally far removed. Could he be seeing a vision of his future self? Or, perhaps he’s gazing at a reflection of his own soul.

Hartmann remarks later, “As art, those paintings go deep. They tell us things we don’t know about ourselves. They act as a mirror for things we don’t normally see reflected.”

Vincent Van Gogh: the cause of all the fuss.

O’Toole described Tanz’s mood shifts as being, “sort of a role within a role. His schizophrenia is only revealed in occasional hints. It’s the mask-and-the-true-face device, always a fascinating challenge.”8

Sharif and O’Toole were initially reluctant to do Generals at all, but were locked into contracts they had signed before Lawrence of Arabia catapulted them to stardom—contracts that reflected their pre-stardom rate! Reportedly, Donald Pleasance was paid two to four times as much as they were for his small but humorous role.

Gore Vidal, a Generals’ screenwriter who wound up uncredited, believed O’Toole may have “sabotaged” the film by intentionally giving a one-note performance because of his lack of compensation.9

It was also reported that though they’d previously bonded after working together for two years on Lawrence of Arabia, O’Toole, and Sharif became adversarial on the set.

At one point, “O’Toole blurted out, ‘Stop asking me so damned many questions—you sound like the bloody major you’re playing!’”

Shot back Sharif, “Stop giving orders—you heel-clicking stormtrooper.”10

All was resolved when they realized they’d started to identify too deeply with the characters they were playing.

Harrison, who spoke on the film’s international Blu-ray release in 2019, thought the film’s major theme was human beings struggling to hold onto their humanity during wartime. If this is true, it’s ironic that the film’s most interesting character visibly lacks any humanity at all. Still, it’s a compelling performance, and one big reason Generals is worth checking out.

Bibliography

1 Curtiss, Thomas Quinn. “To an American Movie, Warsaw Said OK.” The New York Times, May 8, 1966.

2 Scheuer, Philip. “‘Night of the Generals’—Searchlight on a Madness.” The Los Angeles Times, January 29, 1967.

3 Fraser-Cavassoni, Natasha. Sam Spiegel: The Incredible Life and Times of Hollywood’s Most Iconoclastic Producer, the Miracle Worker Who Went from Penniless Refugee to Showbiz Legend, and Made Possible The African Queen, On the Waterfront, The Bridge on the River Kwai, and Lawrence of Arabia. New York: Simon & Schuster, 2003.

4 Harrison, Scott. “Killer Instinct: Sam Spiegel and The Night of the Generals.” Eureka Entertainment, 2019. Blu-ray.

5 Newsweek, February 20, 1967.

6 The Night of the Generals, Columbia Pictures Pressbook, 1967.

7 Masterpiece. 1997. “Peter O’Toole.” Melvyn Bragg interview with O’Toole on his autobiography Loitering with Intent.

8 Curtiss, Thomas Quinn. “To an American Movie, Warsaw Said OK.” The New York Times, May 8, 1966.

9 Fraser-Cavassoni, Natasha. Sam Spiegel: The Incredible Life and Times of Hollywood’s Most Iconoclastic Producer, the Miracle Worker Who Went from Penniless Refugee to Showbiz Legend, and Made Possible The African Queen, On the Waterfront, The Bridge on the River Kwai, and Lawrence of Arabia. New York: Simon & Schuster, 2003.

10 Jackson, George. “Spiegel Re-United Star Team for Saga.” Los Angeles Herald Examiner, January 28, 1967.

Edited by Olga Tchepikova-Treon