| Lucas Hardwick |

The Mosquito Coast plays at the Trylon Cinema from Friday, September 22nd, through Sunday, September 24th. Visit trylon.org for tickets and more information.

Beware: Spoilers Ahead

Believe it or not, instead of earning money by writing for a living, I actually have a real, honest-to-God day job of the blue-collar persuasion where I recently found myself engaged in the spirited pastime of bitching about work with a colleague. It was a heightened moment of blowing off steam concerning the this-and-that of the ever-changing, fluid demands of questionably competent management, when I laughed and said, regarding some company policy, “They’ll change it in a couple of years anyway.” Serious as a heart attack, my co-worker responded, “This country ain’t gonna be here in a couple of years, the rate things are goin’,” and ground the conversation to a screeching halt. The jubilant tone of two comrades with nothing in common but the towering despotism of an unchecked break-rock administration was hushed by darker and more alarming conspiratorial assumptions of a political nature, that, frankly, I preferred to avoid. If there had been laughter from any bystanding crowd, it would’ve trickled into awkward silence. That’s when I knew I wasn’t having the conversation I thought I was having, and that I was talking to one of those guys.

Allie Fox is one of those guys. Allie Fox (Harrison Ford) is the archetypal cynic who sees the nation going to hell in a handbasket because of TV, soda pop, fast food, foreign goods, and all-around modern convenience. He probably doesn’t pay taxes, he wouldn’t be caught dead with a smartphone, and if he votes, it’s definitely on the libertarian ticket. And anyone who gets him started on gas prices will rue the day they dare embark on such small talk. To Allie Fox, the world hasn’t carved its way into the ease of existence but withered into self-destructive shiftlessness instead. Allie Fox loves America so much, he’d leave it before watching it die. As an inventor driven to advance convenience, he is also a bit of a walking contradiction. As Allie’s employer puts it, he’s “the worst kind of pain in the neck: a know-it-all who’s sometimes right.” Allie Fox is the ouroboros swallowing its tail in the spirit of wholeness but destroying itself in the process.

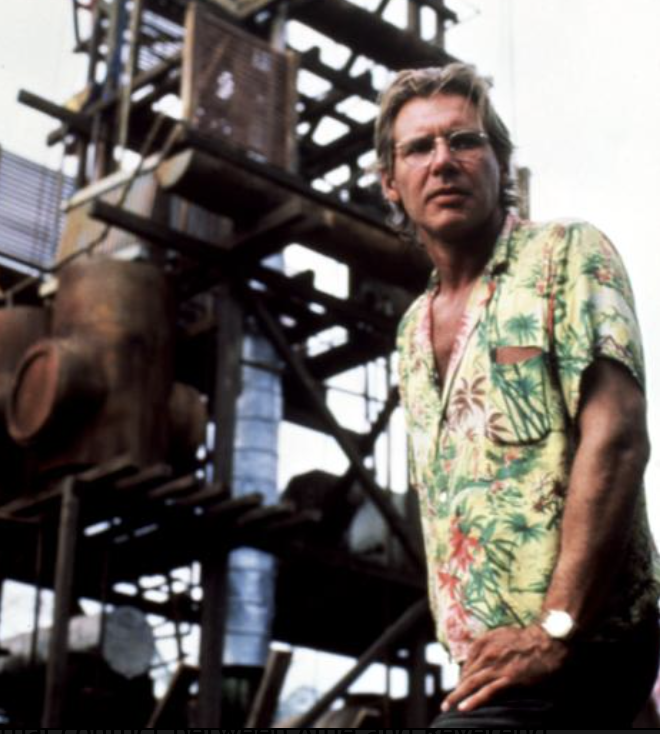

Between roles as varying degrees of the same grumpy guy across three franchises, Harrison Ford occasionally gets to

do some real acting. He disappears into the role of Allie Fox in Peter Weir’s The Mosquito Coast.

In Peter Weir’s 1986 film The Mosquito Coast, inventor and fed-up American Allie Fox is sick of watching the country around him descend into an age of waste. He’s a “wake up, sheeple” kind of guy who’s got some real intelligence to back up his claims—he “dropped out of Harvard to get an education,” after all. Allie’s brilliance for creating ice from fire is unappreciated on the farm where he works, so he packs up his family and his inventions to start anew in the wilds of the Central American jungles where he plans to enlighten “primitive” peoples with his ice making contraption and change their lives forever.

The difference between Allie and the average conspiracy theory wacko that we too often find ourselves conversing with when we deign to engage with strangers is Allie’s motivations aren’t politically charged—they’re much bigger than that. Allie’s problem with the world is systemic, rooted in something to do with ourselves. In one of Allie’s verbal onslaughts indicting modern society, he says, “We eat when we’re not hungry, drink when we’re not thirsty. We buy what we don’t need and throw away everything that’s useful,” and so on. He is, indeed, a “know-it-all who’s sometimes right.”

Ice, ice baby.

It’s important to take a moment and discuss Allie’s new-to-natives commodity and the fact that its big selling point is convenience. It’s convenient in the sense that Allie is correct; it most certainly could change the lives of the people of La Mosquitia. What’s good for Allie is, he’s the only ice game in town. The irony is, he’s establishing the very thing he hates that’s happening back in America. His price: loyalty? Textbook capitalism. (Shhh. Don’t tell Allie.) But Allie’s incessant zeal for innovating the foliage-filled tropics into a cool and cozy self-sufficient estate, along with shilling his giant magic Fridgadaire to demand acceptance from poor, indigenous people also smells a little like cult leader to me.

Our relationship with Allie is as antithetical as Allie’s contemptuous relationship is with the world around him. On one hand, we openly embrace his efficient, “fuck the system” spirit; but on the other hand, we see the makings of a charismatic leader drunk on his own wack-a-doo ideology. This conflicting perception of Allie is directly reflected in the attitudes and varying loyalty of his two sons, Charlie and Jerry (River Phoenix and Jadrien Steele). Charlie is open to his father’s ideals, but grounded enough to know to proceed with caution. At one point in the film, in an attempt to quell his family’s desires to return to the free world, Allie lies and tells them that a nuclear holocaust has wiped America off the face of the planet (fake news). Afterward, his son Charlie admits (in a reflective voice-over monologue): “I wanted to take hold of him, to tell him I loved him and that I’d stay and work beside him forever if only he would take back the lie.” Meanwhile, younger son Jerry more than once openly reveals to his brother that he wishes their father was dead. Charlie’s conflict is based on how he feels for his dad, while Jerry’s feelings are more active. Both sons’ reactions to their father appeal to how we, too, feel about the man. As one of the migrant workers says at the beginning of the film, unintentionally falling in line with Allie’s long game, “He my father, too. We all his children.”

Allie and family.

It’s tough to pin down Allie’s precise intentions. Does he really want to bring innovation to indigenous people? By his rationale, they already have it made. They’ve lived for centuries without ice, so why is he eager to violate what’s referred to in Star Trek as the Prime Directive, and muck up less technologically developed cultures with pesky advancements like ice? If you ask Allie, it sure beats the Christianity that Reverend Spellgood (Andre Gregory) is hawking in the next village over. But whether Allie admits it or not (and trust me, he won’t), he and the good reverend are in the same business—capitalizing on the dispossessed. In a scene where the two men face off with each other, Spellgood sports a crucifix lapel pin representative of Christ’s sacrifice for mankind, while Allie carries a hammer parabolic to Christ’s role as a carpenter. These men are conceivably in the service of saving humankind, but with different versions of the same truth to deal. Christ was a savior, Christ was a carpenter. The ouroboros continues eating its tail in a strange instance of conflict where two things are true at the same time.

When a gang of guerrillas invades Allie’s Swiss Family Robinson AirBnB, Allie destroys his own hard-earned creation before relenting to the demands of rainforest ruffians, just like he bailed on a dying America. And to bring Allie’s crisis to critical mass, his attempt to literally freeze the intruders results in his own personal 9/11, destroying his one-stop shop into the 20th century. Imagine Allie’s fury when all that remains of his jungle compound is a houseboat as it sails past the thriving missionary community down the river. Allie exacts that fury in a blaze of glory, destroying Spellgood’s gas generator-powered tropical Sunday school and insisting that his family can continue their rugged existence and flourish on coastal washed-up remains. At this point in the film, we truly realize that Allie is a dangerous guy, so consumed with his own beliefs that come hell or high water (quite literally), he’s determined to not only be the smartest guy in the room, but also the rightest. Fragile ego a-go-go.

Allie and his migrant workers prepare a ramp for transporting ice and equipment to their camp.

It’s unfortunate that the film doesn’t explore the apparent trauma Allie’s long-suffering, loyal wife has endured in her spousal role. There are moments when we see she’s quite aware of who she’s married, but it’s clear that she loves him and that he’s good to her. But living with Allie obviously takes a lot of energy. Beyond a mild breakdown near the end of the film, Mother Fox (Helen Mirren) is only quietly apprehensive and mostly supportive of Allie’s ambitions. Let’s remember; we’re talking about screenwriter Paul Schrader here, who adapted the script from the novel by Paul Theroux. Schrader doesn’t exactly make the female voice a priority in most cases, but for human islands like Allie Fox, he’s perfect.

The Mosquito Coast is a film about lies and facades; the lie that Allie believes America has become; the lie covering his insecurities; the lie that ice will change a civilization that never needed it to begin with; the implied lie of missionaries; and the lie that Allie makes up for himself as a man with a vision. His mission started as a long-winded tirade until he put his money where his mouth was and cashed in on his intentions, and the innovation of convenience convenienced him right into oblivion. Remind you of any other charismatic leaders who started their campaign as a joke?

The film culminates in a beautifully poetic ending symbolic of the world Allie believed he lived in. He’s dying of a wound from a preacher’s gun as his family sails out to sea. Or are they headed up the coast, back to their own “civilization”? I guess it depends on how Allie Fox you are. Either way, Allie disapproves of both destinations, but his loving wife lies and tells him they’re headed back upriver to fulfill the destiny he’d anticipated for them. Allie’s family becomes emblematic of an America unsure of its harbor, but one that is moving forward and will still be around in a couple of years whether or not it has ice for its drinks.

Edited by Olga Tchepikova-Treon