| Luke Mosher |

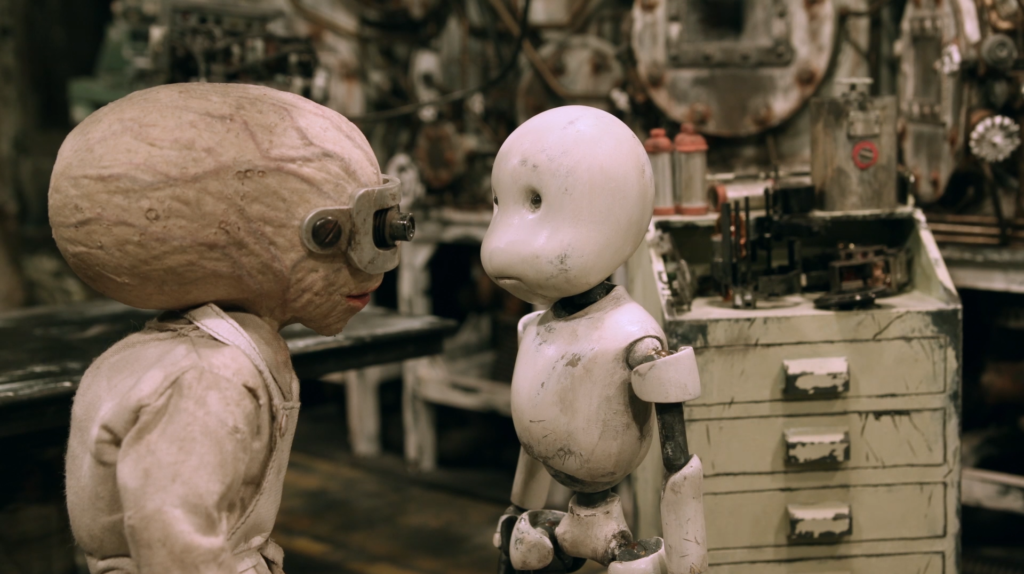

The scientist and Parton, with a newly built body.

Junk Head plays at the Trylon Cinema from Friday, December 1st through Sunday, December 3rd. Visit trylon.org for tickets and more information.

Among the many kinds of new films released every year, I often find animation the most exciting. The form is endlessly malleable, and animators are always finding new techniques to dazzle and new worlds to explore. Takehide Hori’s one-man production Junk Head (2021) is one such wonder: a sci-fi-horror-comedy stop-motion film whose story of creation is as impressive as the film itself.

The film’s story is set in the far future. Humanity has gained immortality through cybernetics but lost the ability to reproduce. People now live in the top stories of mega-structures, where they are hermetically sealed into apartments and communicate with each other through holographic video. A deadly virus is wiping out the remaining human population and the government is paying volunteers to venture to the lower depths in search of a solution for infertility. (You may feel uncanny flashbacks to the COVID-19 pandemic, but Junk Head was conceived over a decade before.)

Our noble hero is one such volunteer, a posh upper-class man named Parton who enlists for adventure (and a little extra cash). His mission is to study the denizens of the lower levels, who were originally cloned from humans to develop the underworld. After a rebellion 1,600 years ago they separated from humanity to form their own society in the depths. Parton enters a pod that descends to the lower levels but his quest is derailed when he is blown apart by a rocket launcher. All that survives is his head. He’s rescued by a scientist and his three henchmen—creatures that look like demented, cyberpunk versions of the penguins in the Madagascar movies and behave like the Three Stooges. The scientist frankensteins a robotic body together from scrap parts and sticks Parton’s head on top, hence the film’s name: Junk Head.

The “Valve Village,” which took over six months to build.

Parton suffers amnesia from his head trauma, but when his memories slowly return he takes up his initial quest. The middle of the movie is episodic and follows Parton on his misadventures in the underworld, where he meets zany characters and blood-curdling monsters. The 2nd act does meander a bit, but part of the fun of the film is exploring its bizarro world. Much of the film’s narrative drama comes not so much from the heroic quest story that’s initially set up, but from the fish-out-of-water aspect that’s equal part horror and comedy as Parton explores the netherworld and its strange citizens.

The story eventually circles back to its quest premise in the third act with a rousing finale that involves the three zany henchmen and Parton fighting a Xenomorph-esque monster, and an ending that is surprisingly emotional. Some plot threads are resolved but others are left dangling, and the movie ends rather abruptly. One thing that may not be apparent going into the film that you may find helpful is that this is the first film in a projected trilogy, so know that the story does not end here. Director Takehide Hori reportedly has a sequel named Junk World set to release in 2025, with a third and final film to follow.1

Junk Head is a movie that proudly wears its influences on its sleeve. The animation elements are reminiscent of the stop-motion work of Jan Švankmajer and the Quay Brothers, who use clay, dolls, and found objects to creepy effect. Aesthetically, the film feels like a weird mix of the sci-fi nightmares of H.R. Geiger, the cyberpunk body horror of Tetsuo: The Iron Man (1989), and the labyrinthine tunnels and hellish monsters of Hellbound: Hellraiser II (1988). The best direct comparison, one that must inevitably be made by anyone writing about Junk Head, is to Phil Tippett’s Mad God (2021),2 to which it bears a truly uncanny resemblance. The similarities are entirely coincidental as their productions were running at the same time, though Hori does cite Tippett’s special effect work in movies like Jurassic Park as an influence. Mad God is also a stop-motion animation about a character on a mysterious quest through the underworld that was created almost entirely by one person. When Tippett saw Junk Head, he made the comparisons too. Hori said in an interview, “Phil [Tippett] told me that he saw Junk Head, and he said that ‘we might have [been] born from the same egg,’ and ‘I feel so close to you creatively.’ I was so glad to hear that.”3

Takehide Hori and his miniatures, built 1/6th scale. Image Credit: “Making Of,” Yamiken, 2022, https://www.yamiken.com/making-photoes (accessed November 18, 2023).

Besides the fully realized world of the film, the most remarkable thing about Junk Head is that it was created almost entirely by just one guy.4 Takehide Hori is responsible for nearly every element of the film, with a small crew of four helping with additional voice acting, sound, and animation. Perhaps even more impressive, Hori is entirely self-taught. He looked up what he needed to learn about stop-motion filmmaking in books or on the internet. This DIY aspect is part of the charm of Junk Head. It feels like a feature-length version of the odd outsider-art animation you might find on Newgrounds or early YouTube. Thanks to modern technology and the internet, anyone could become a filmmaker with the right motivation.

Despite having no background in film production, Hori decided in 2009 at age 38 to make a movie. He was inspired by the anime director Makoto Shinkai, who famously made his first OVA Voices of a Distant Star (2002) by himself on a Macintosh computer.5 Stop-motion animation seemed like an easy medium for Hori to start with, but he quickly realized how painstaking the process would be. Stop-motion animation is captured through a process of taking a picture, moving a miniature an almost imperceptible amount, taking another picture, and repeating ad nauseam. Some quick back-of-the-napkin math shows the compounding amount of work that goes into it: 24 frames per second x 60 seconds per minute x 100-minute runtime = 144,000 individual photos, which Hori took almost entirely himself.6 He said in an interview: “It was all my misunderstanding, because stop-motion looked really easy, I thought….[with] stop-motion animation, all you have to do is that you create [the miniatures], you move it, take a shot, easy. How wrong was I?”7

It took four years for Hori to create his first stop-motion short, Junk Head 1, a 30-minute short that would become the first third of Junk Head. He had experience with set design from his background as an interior designer for amusement parks, a skill that translated well to making miniatures and sets. He relegated his professional work to one weekend a month and spent the rest of his time making the short. He crafted miniatures from clay, plastic, and other materials, and built 1/6th scaled sets in his design warehouse. One set in particular, the “Valve Village” which looks like a power plant for steam, took six months to build.

Our noble hero Parton, oblivious to the dangers of the underworld.

Hori finished Junk Head 1 in 2013 and uploaded it to YouTube, where it received a positive response but little widespread recognition. A crowdfunding effort to expand the short into a feature-length film fell through, as did offers from Hollywood, but eventually Hori secured financial backing from a Japanese firm. International buzz from the YouTube short built over the next four years, including a shoutout from Guillermo del Toro, who tweeted: “Amazing short! Give yourselves a treat! A One-man band work of deranged brilliance! Monumental will and imagination at work.” Hori finally finished the feature-length Junk Head in 2017 and debuted it at festivals, where it won the Best Animated Feature Award at the Fantasia International Film Festival in Canada and the Best Director of a New Wave Feature Award at Fantastic Fest in the U.S.

Seeing even a few stills of the film makes it easy to understand why the film world went gaga for Junk Head. Its artistry is nothing short of spectacular, and the work Hori put into his subterranean world and its nightmarish creatures shines through in every frame. Everything from the cyberpunk sets to the handcrafted clay monsters reflects a unique, singular vision. A word of warning to those who haven’t seen the trailer: this isn’t your typical LAIKA stop-motion animation. The world of Junk Head is bizarre, violent, and gross. But animation junkies looking for films that push the craft to new places wouldn’t have it any other way.

In a time of endless, forgettable streaming content and IP-driven movies that feel like they were created in boardrooms, Junk Head is a breath of fresh air. Every aspect of the world and its inhabitants is handcrafted—quite literally. The film proves that animation knows no bounds, and that there are many worlds left for the medium to explore. I eagerly await Junk World and whatever wonders might follow.

Bibliography

1 Kara Dennison, “Bask in the Surreal Visuals of Stop-Motion Animated Sequel JUNK WORLD Trailer,” Crunchyroll, August 24, 2023, https://www.crunchyroll.com/news/latest/2023/8/24/japanese-stop-motion-animated-film-junk-head-announces-sequel-junk-world-coming-in-2025.

2 Mad God was shown at Trylon last year and Joe Midthun has a great Perispherearticle about the film and Tippett’s contribution to special effects and stop-motion animation.

3 Kambole Campbell, “Takehide Hori: ‘Everything Started From My Misunderstanding’,” Little White Lies, April 22, 2023, https://lwlies.com/interviews/takehide-hori-everything-started-from-my-misunderstanding/

4 The story of making Junk Head are taken from two interviews with Hori: Kambole Campbell, “’Everything Started From My Misunderstanding’” and: Takeshi Ishii, “Post-Apocalyptic Film Junk Head Lauded as ‘Work of Deranged Brilliance’ by Guillermo del Toro,” JapanForward, April 9, 2021, https://japan-forward.com/post-apocalyptic-film-junk-head-lauded-as-work-of-deranged-brilliance-by-guillermo-del-toro/#:~:text=Academy%20Award-winning%20director%20Guillermo,will%20and%20imagination%20at%20work.

5 OVA = Original Video Release. It’s the Japanese equivalent of a direct-to-video release in the U.S.

6 Many thanks to Takeshi Ishii for pointing out these mind-boggling numbers in “Post-Apocalyptic Film Junk Head.”

7 Campbell, “Takehide Hori: ‘Everything Started From My Misunderstanding.’”

Edited by Olga Tchepikova-Treon