| Dan Howard |

Memories of Murder plays at the Trylon Cinema from Sunday, January 7th, through Tuesday, January 9th. Visit trylon.org for tickets and more information.

My first foray into Bong Joon-Ho’s unparalleled cinematic mind was at the very start of the COVID-19 shutdown. While confined to my home like everyone else, I took the opportunity to catch up on some movies I hadn’t seen, and Parasite was one of the first films I watched. Needless to say, it had a profound effect on me; I understood all the hype it had been receiving. I was hooked on Bong Joon-Ho and was eager for more, viewing Incoherence and Memories of Murder next. Now, much like with horror movies, when it comes to serial killer films, I am extremely picky. It’s a genre that’s been done to death even before Memories, and it’s been the go-to story type for most detective films. But what Bong Joon-Ho achieved in his first masterpiece set a new standard for serial killer stories that others have rarely come close to since.

Based on real events, Memories of Murder focuses on a group of detectives hunting a serial killer in a small South Korean town in 1986. While they only seem to care about finding SOMEONE to convict (using methods of torture and planting false evidence), Detective Seo arrives from Seoul to aid in the investigation. He questions the local detectives’ methods; especially the mantra of Detective Park that “not thinking” will get you farther in a small-town murder case.

When Memories of Murder was first released in 2003, the identity of the murderer, who is based on a real-life serial killer, had remained unsolved. It took me a few viewings to really see the deep, subtle complexity that Bong went for in the film’s narrative, where audiences can see the story both from the detectives’ perspectives and from the viewpoint of the killer. But the latter does not unfold in the way you’d expect. When you compare the Korean detectives’ tactics to those of their American counterparts, they seem disorganized. They spout off wild theories and just are just all-around amateurish even for a small-town police department. Whether the detectives who investigated the actual case were like the cops in the film or not means very little in the scope of the film. When Bong made Memories of Murder, he confirmed in an interview of what his deep intuition was telling him at the time: that the killer would most likely see the movie. While the film unfolds mainly from the point of view of the detectives, it feels like it offers a view of these detectives from the mind of the killer as well. In many ways, they are these incompetent buffoons that are easy to toy with and manipulate.

The very first shot we see is a young Korean boy looking at a grasshopper sitting on a large blade of grass. While Bong helps set the tone for the town—a quiet community where nothing heinous really happens. The shot is a perfect metaphor for how this murderous psychopath views his victims: they are insects he can crush whenever he wants. This is something I only recognized upon my latest viewing of the film: the underlying duality of the film’s perspectives. Bong’s eccentric portrait of South Korean detectives from the 80s—often cartoon-like with all their jump kicks, trying to keep a crime scene intact in a scenario that more resembles something out of Looney Tunes—strangely helps make the film feel more grounded and honest. Rather than trying to write the characters as, well, the typical detectives-hunting-serial killers that you would see in films like Se7en, Bong seems to be more interested in telling a story about the real folks involved in the investigation and shed some light on South Korean history. And while the detectives aren’t necessarily good at their jobs, they still are relatable characters, for better or worse.

For example, Detective Park has unique intuition where he can tell if a person is guilty or not just by looking into their eyes. He claims that “There’s a reason people say I have a Shaman’s eyes,” rendering him as a perfect Ying to Detective Seo’s by-the-book/big-city-cop Yang. Neither particularly agrees with the other’s tactics and outlooks, but they balance each other while actively investigating the crimes that are being committed practically down the street. How many of us have ever met someone who’s challenged us and, as a result, helped us to grow? It doesn’t happen often, but when it does, those alternate perspectives can forever change how we see the world and ourselves.

When Memories of Murder went into production, Bong knew exactly what he was doing with the film. He knew the killer was still out there and he knew the killer would probably go see the film. Bong manages to both craft a narrative that simultaneously helps us to see the struggles of the detectives and offers the killer a strange sense of superiority by showing the cops struggle to catch him and failing. I mean, as much as it turns my stomach to think about it, I can’t help but wonder if there’s that possibility of a silent feeling of victory the killer has. Later, I found out that Lee Choon-Jae, the real killer, was already in prison, serving a life sentence for killing his sister-in-law in 1994. Detectives finally found evidence connecting him to the crimes in 2019, where he initially denied the claims, but later confessed. After discovering this, I couldn’t help but think about his state of mind: “How affected did he feel? How much guilt did he have? How much was he haunted by his actions?” I wonder if he was able to even see the movie, or if he wants to see it at all. That’s where Bong’s brilliant technique of dual perspective comes into play. You can watch the film and see it as from the point of view of the detectives AND watch it from the view of the killer and what he thinks the investigation of his crimes must have been like back in the day. The payoff of these dual perspectives comes together at the end in the best, most unsettling way possible.

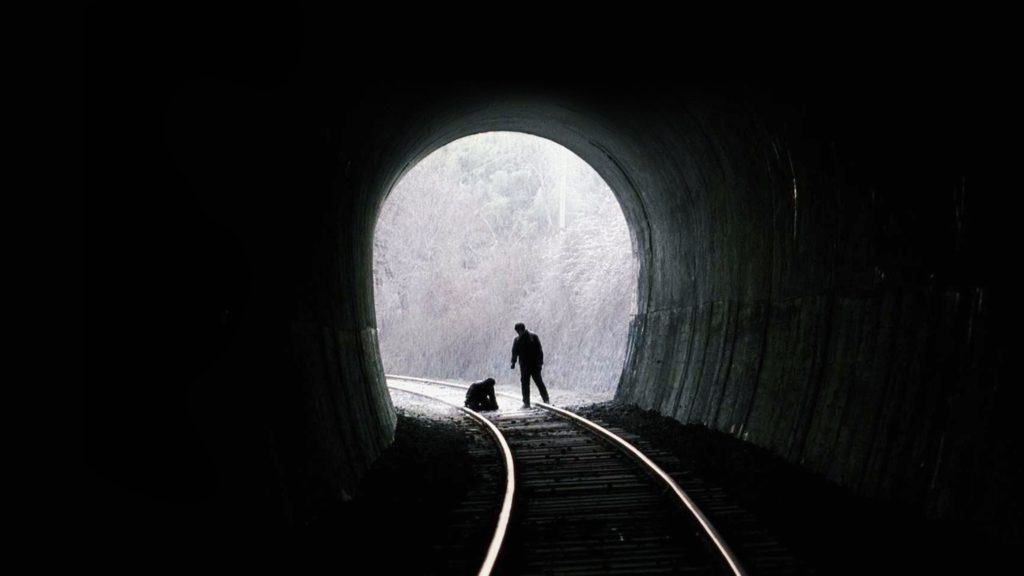

However, what initially struck me the most about the film is not any of its plays with particular viewpoints. It’s the look Detective Park has on his face at the end when he gazes straight into the camera. Without giving too many details of the scene in question, Park receives a revelation about the identity of the killer which causes him to look straight at the camera. Since Memories wasn’t the first film of Bong’s I had seen, I initially brushed this shot off as him using one of his signature shots. Every great director uses similar kinds of shots/moments across many of their films, after all. But then I realized what that look really meant. It was Park/Song Kang-ho looking directly at the killer sitting in the audience of whichever theater he’s watching this film about his crimes. Bong had a strong feeling that the killer would see the film. The final shot thus is the perfect tactic to subtly break through the screen and look out at the killer to confront his monstrosity in the most direct way. But it also puts the audience on edge—at least those who are able to figure out themselves that the killer could very well be sitting next to them in the theater. He could be next to you on the bus, in the store, etc. How would that not give you chills?

Any time a film or TV series is based on real events, there are things I can’t help but wonder about: Did Bong have that fear himself while going into production? Word could have easily gotten around that the film was being made. This man that has evaded the law for nearly two decades could have very easily shown up either on set or somewhere near the set. How did the cast and crew feel about the possibility? How did the real detectives feel about the film? Did they still feel that fear of the man they hunted for so long? I can imagine it must be daunting watching the film with these characters that are based on them and all the mixed emotions that ensued.

The intentions of those turning these kinds of stories into a film or series can always be questionable, but in the rare case where they can bring attention to murders that others probably weren’t aware of or would pay attention to otherwise. Memories of Murder is one of the few that was made with the best intentions. In his effort to bring these unsolved crimes to light, Bong crafts a complex, often cynical but somewhat hopeful story of these deeply flawed characters and their unconventional methods of seeking justice, uprooting the core of who each of these detectives are, and how you go on living knowing you couldn’t avenge these women who met their grim fates the way they did. How do you go on living knowing that the man you were trying so hard to catch is still or could still be out there? Bong manages to make you feel that kind of real-life paranoia; it’s almost like Hitchcock was giving him pointers for how to keep the audience on the edge of their seats. Bong’s own version of Hitchcock’s bomb theory, if you will, is the killer in Memories of Murder; it’s his own type of “Shaman Eyes.” If I were to ever suggest to anyone aspiring to write a crime/serial killer story, novel, or film, where to look for inspiration and guidance, Memories of Murder would be at the top of the list.

Edited by Olga Tchepikova-Treon