|Sophie Durbin|

Black Narcissus plays at the Trylon Cinema from Friday, March 8th, through Sunday, March 10th. Visit trylon.org for tickets and more information.

In the typical haunted house movie, the protagonist and their loved ones move into a house and stay put despite the fact that it has a million red flags (creepy caretaker, suspicious sounds at night, blood oozing from the elevators…). By the time the entire social order of the film collapses and everyone is dead or dying, they realize—hey, maybe I shouldn’t have stayed here! Black Narcissus plays out a bit like this. It’s a haunted house movie, but instead of driving everyone crazy from fear, they’re driven crazy by sexual repression.

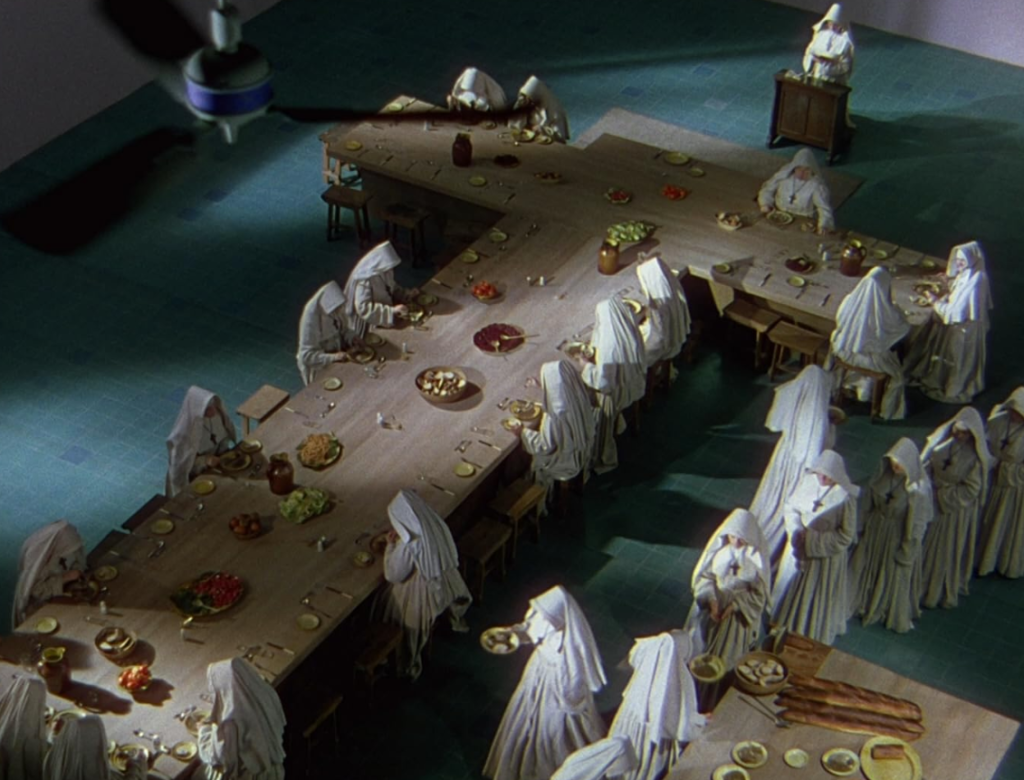

The nuns of Black Narcissus are doomed from the beginning. A convent setting up a school/hospital hybrid in a crumbling palace that used to house a harem? With a cranky housekeeper and a holy man who won’t stay off the property? In a Powell and Pressburger movie? These women don’t stand a chance. Sister Clodagh (Deborah Kerr) makes a valiant effort, but the more she tries to deny the power of the palace and its mystical environment, the more she and her fellow nuns fall under its spell. But because it’s 1947, it’s a fascinating case study of just how much can be implied when the censors are on high alert and the directors are dealing with an audience simultaneously thirsty for wholesome postwar family fun and salacious intrigue.

The palace is a container for things that cannot be contained and is filled with reminders that it used to be a harem house. Since every sister in the convent has chosen a life of celibacy, the tawdry murals are a daily reminder that the previous inhabitants chose the opposite. The beauty of the outside world spills into every room. We never stop hearing the wind as it whips through the halls. They complain in code: the air is too clear, the mountains so high. The nuns never explicitly reveal what’s so distracting about the palace, but perhaps that’s part of the point: they’re haunted by something irrational that cannot be planned or categorized like their regimented cloistered lives. Part of Sister Clodagh’s futile mission is to keep the order together, but the mountains, sky and atmosphere of the Himalayas work together with the palace to unspool them all. Sister Philippa, the gardener, plants flowers instead of vegetables. Sister Honey steps outside of medical protocol. Sister Ruth starts acting secretive and cruel. This is particularly threatening to this order of nuns because they all renew their vows annually—if the school is unsuccessful and the sisters go home, the order will collapse.

While “repressed nun comes undone” might be a common enough trope, it’s never very titillating to watch the sisters throughout most of Black Narcissus. Their habits seem ridiculously drab compared to the villagers’ colorful garb. When Sister Ruth appears in civilian clothing in her final moments, she looks far more threatening than she does enticing. Powell and Pressburger save most of the sex appeal for the men. David Farrar as Dean saunters around in short shorts and an open shirt. He has little interest in any of the women except for Sister Clodagh, who happens to be the one least available to him. When female sexuality is depicted explicitly, it becomes ridiculous. See Jean Simmons’s performance as Kanchi, a foil to the nuns: she wiggles and sways in her best imitation of an unrestrained “local girl.” It’s actually interesting to see how Jean Simmons handles the performance. Yes, she employs a mishmash of dated stereotypes. But there are moments of surprising intensity. Think about when she screams hysterically on the ground as Ayah the housekeeper whips her for “stealing in the house.” Kanchi represents the logical extent of what the palace and its environs will do to unravel and expose the female id (of course, this also foreshadows what happens to Sister Ruth later). When she’s saved by the sensitive Young General (a lovely turn from Sabu), who throws the switch away and adorns her with a jeweled necklace, Kanchi collapses into his arms. It’s exhausting being that unhinged.

The haunted house parallels are most dramatic in the climactic scene, when Sister Ruth attempts to throw Sister Clodagh off the cliff. Flinging open the door of the palace in a moment resembling a jump scare, Sister Ruth looks completely transformed. She’s no longer a troubled nun or a failed seductress—she’s an otherworldly she-demon, moved by forces beyond her control (I’m reminded of the final moments of The Red Shoes, Powell and Pressburger’s film from just a year later, when Moira Shearer is compelled by the shoes to leap from the balcony to her death). When she ends up falling to her death, the final moments do away with any concerns the audience may have had about rogue nuns being rewarded for their immorality. Here, Sister Ruth is punished for stepping too far outside the bounds of her vows, both literally and metaphorically. In an earlier scene, Sister Philippa, exasperated, shares that in this environment, one must be like Dean or the holy man: you must ignore it or give yourself up to it. In these final moments, the palace grounds themselves make this decision for Sister Ruth.

Edited by Finn Odum