| Patrick Clifford |

Touch of Evil plays on glorious 35mm at the Trylon Cinema from Sunday, June 2nd through Tuesday, June 4th. Visit trylon.org for tickets and more information.

“Oh man! You’ve never seen Touch of Evil?”

“Oh… Man. That first shot!”

“Tick, tick, tick, tick… tacka-tooka, tacka-tooka…”

This was how my good friend Juan Torres introduced me to Touch of Evil. Long ago, when we were college students in Chicago. I can still see the excitement in his eyes as he teased the soundtrack to life with great attention to both the timer and the bongos that lead you onto the rollercoaster that is the film’s opening shot.

And fuuuuuhh. What an opening shot it was. And always will be. It is prime, mid-career Orson Welles testing the wheels on a film that gave him the artistic freedom he lived for yet rarely had the opportunity to chase. It had close-up details and bird’s eye perspective. It created mood and expressed tension. It established characters and story. It started in Mexico and ended in America. It was a first shot that announced the return of an artist and a master.

Maybe this single, 3+ minute tracking shot, perfectly married to a Henry Mancini score that Juan really kinda nailed, was pent up energy. I mean, this was a guy who hadn’t been entrusted with the helm of a Hollywood production for over 10 years. And this is the same guy who Produced, Co-Wrote, Directed, and Starred in Citizen Kane at the age of 25—considered by critics of the highest order of snobbery to be the greatest movie of all time. The same guy who, even before that, made an entire nation believe that aliens had invaded the earth and were in fact at war with the world. On the radio.

But Touch of Evil was never intended to be an Orson Welles artistic tour de force. Instead, it kind of fell into his lap. He had recently returned to America after spending over 10 years abroad. Frustrated by the unceremonious response to his return, Welles found himself taking a role in a B-Western produced by Universal Pictures called Man in the Shadow. Welles wasn’t happy with his circumstances and felt the role was really hitting bottom for him.1 It did, however, lead Universal to send him an offer for another role, this time as a crooked detective. While considering it, Universal tempted budding leading man Charlton Heston to co-star by telling him Welles was onboard. Heston misunderstood and stated, “Well, any picture that Welles directs, I’ll make.”1 Universal quickly covered its tracks by offering Welles the director’s chair. Welles went for broke, saying he would, but only if he could re-write it. And with that, Touch of Evil became Orson Welles’s first Hollywood financed film in a decade. It would also be his last.

Welles’s first task was to rewrite the script. Instead of reading the book it was based on, he couldn’t help but focus on what interested him when he first got wind of the project: the idea that a detective with a good record would plant evidence on a suspect who, in the end, turns out to be guilty anyway.1

Go ahead. Read that last sentence again. If you’re like me, you still don’t know what to do with it. Because it suggests conflicting thoughts about the detective. Sure, nobody’s a fan of detectives who plant evidence. But like, how did he know? And why does he have a good record?

It’s an idea that poses more questions than answers.

And I think that’s precisely what sparked Welles to start there. He has absolutely no desire to tell a story the audience has seen before. One where good and bad are neatly packaged and clearly marked. Exactly the type of product Hollywood seemed to be cranking out like Happy Meals of late.

Around this time, Welles made his feelings clear in an article he wrote for Esquire about the death of Hollywood. In it, he states his beliefs that Hollywood had become a factory seeking mainstream respectability and profitability above all else. Welles longed for the artistry, absurdity, and originality of Hollywood’s earlier years. He wrote, “What’s valid on the stage or screen is never a mere professional effort and certainly not an industrial product. Whatever is valuable must, in its final analysis, be a work of art.”1

While Hollywood still appreciated Welles for his magnetic on-screen presence and the box office draw of his name, it was more reluctant to hand over the keys to an entire production. Other than The Stranger (1946)—a film Welles would eventually and not unironically disown from his oeuvre—none of Welles’ films, including Citizen Kane, were considered successful financially.

Welles may not have known Touch of Evil was a both a gift and a test. And I’d like to think he wouldn’t have cared. He happily pounced at the opportunity to reclaim his triple crown status as writer/director/star and the control it afforded. Despite his misgivings with Hollywood’s output, he relished the resources and highly skilled pros that made it hum. Thanks to his reputation and personality, he would assemble the most talented cast and crew on the planet and do his best to see what he could pull off.

Ultimately, what makes Touch of Evil so thrilling and enjoyable to watch is Welles’s love of cinema as an art form on full display. The camera work I’ve already gushed over continues to dazzle with the perfect balance of what it reveals and what it hides—delightfully full of signs and clues that feed the narrative. There’s music meant to madden the senses, hilariously terrifying 1950s drug commentary, screen-stealing cameos from Golden Age legends and future stars. It’s all extra buttery popcorn worthy.

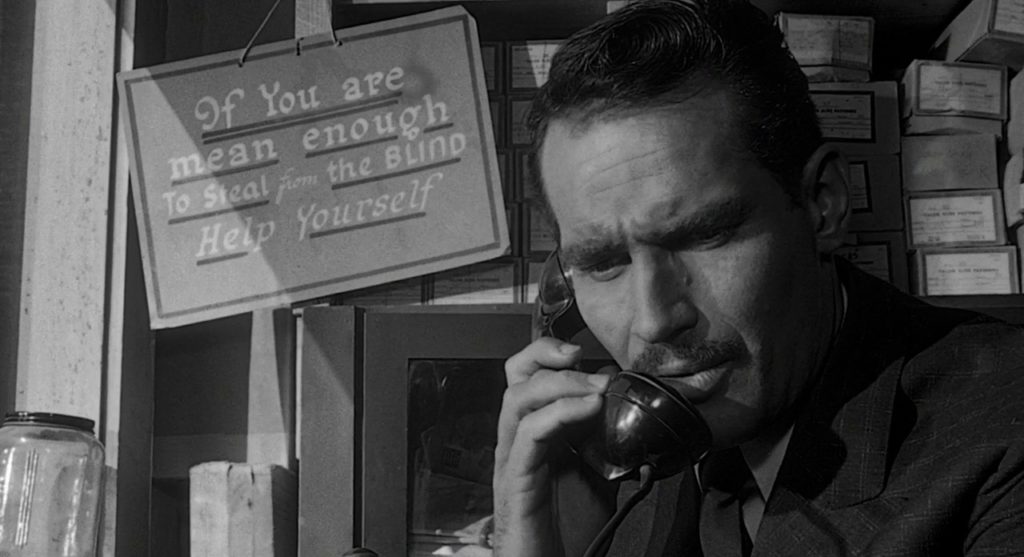

But it’s the story of betrayal and how far this corrupt detective is willing to go to get away with it that keeps us wandering the border town streets of Touch of Evil. Welles delights in the grotesque layer of filth that coats Detective Hank Quinlan. He’s a glutinous, sweaty, candy-bar munching, whiskey-swilling, leg-dragging racist on a morally ambiguous quest for justice. Ever since the killer who murdered his wife got away, he catches killers his way. His inability to resolve that murder—in his mind and in the eyes of the law, committed by a “half-breed” —combined with his dirty job as a border town cop, cements his futureless existence as a slave to betrayal. Quinlan’s trusty sidekick, Sgt. Pete Menzies, transforms from accomplice to hangman as he comes to realize, with impeccable believability from actor Joseph Calleia, that Quinlan’s betrayal comes at everyone else’s expense, including his. Quinlan’s reluctant pursuer is a Mexican narcotics officer named Mike Vargas—played with the assured no-nonsense charisma that would become the trademark of Charlton Heston’s career. Vargas is caught between a honeymoon with his American bride (a fearless and badass Janet Leigh) and the scare tactics of the Grandi family drug ring (led by toupee wearing wannabe gangster Uncle Joe, played with full gusto by Akim Tamiroff). Neither can pull him away from the blatant, constant betrayal of justice that Quinlan rubs in his face. The web only gets more tangled as alliances are made and broken in a constant shuffling of motives and traps. There is no tidy ending. No moral victory. Only remarkable characters brought to life by incredible performances under the masterful direction and pen of Orson Welles.

In particular, I can’t not call out Dennis Weaver’s motel night man and Marlene Dietrich’s chili-slinging, cigarillo-puffing Tanya as examples of the joy that Welles hoped to produce in making Touch of Evil, and sometimes got away with.

By the time Universal Pictures started seeing rough cuts of Touch of Evil, Welles’s artistic license saw its own forms of betrayal. Universal went behind Welles’s back, adding rewrites and shoots under alternate direction. Never satisfied that it would be a commercial success, they underpromoted and under-distributed their final product.

In the end, Detective Quinlan does not get away with it. But he never, ever stops trying—even as he floats away, down the river that divides two countries struggling for common ground.

In later conversations with Peter Bogdanovich about Touch of Evil, Welles says, “It’s all about betrayal—isn’t it?”1

And then there is Marlene Dietrich’s closing line, “He was some kind of man. What does it matter what you say about people?”

The “Reconstructed Version” showing at The Trylon Cinema is the closest thing to a Director’s Cut and contains an extra 15 minutes of footage compared to the 1958 theatrical release. Juan and I say, “Go see it.”

The incredibly valuable and interesting insights that I have referenced frequently in this article on Welles and Touch of Evil came from the great book, This is Orson Welles, by Peter Bogdanovich and Orson Welles. I recommend it highly.

Footnotes

1 Orson Welles and Peter Bogdanovich, This is Orson Welles (Da Capo Press, 1998).

Edited by Olga Tchepikova-Treon