| Bob Aulert |

The Player plays at the Trylon Cinema from Sunday, June 9th through Tuesday, June 11th. Visit trylon.org for tickets and more information.

— Oscar Levant

In the realm of meta-cinematic narratives, few films have achieved the level of sharp satire and self-awareness as Robert Altman’s 1992 film The Player. It’s a two hour long “Fuck You” from Altman to the mainstream film industry; a scathing commentary on the inner workings of Hollywood, delivered through a labyrinthine plot that blurs the lines between reality and fiction. With its intricate storytelling and astute observations, The Player stands as a multidimensional work that not only entertains but also completely assassinates the very industry it portrays.

At its core, The Player is a dark comedy that follows Griffin Mill (played with cynical charm by Tim Robbins), a studio executive who becomes embroiled in a web of intrigue and murder. The narrative unfolds against the backdrop of Hollywood, where power dynamics, artistic integrity, and the commodification of creativity collide. Altman deftly navigates these themes, using Mill’s character as a lens through which to examine the industry’s moral ambiguity and cutthroat nature.

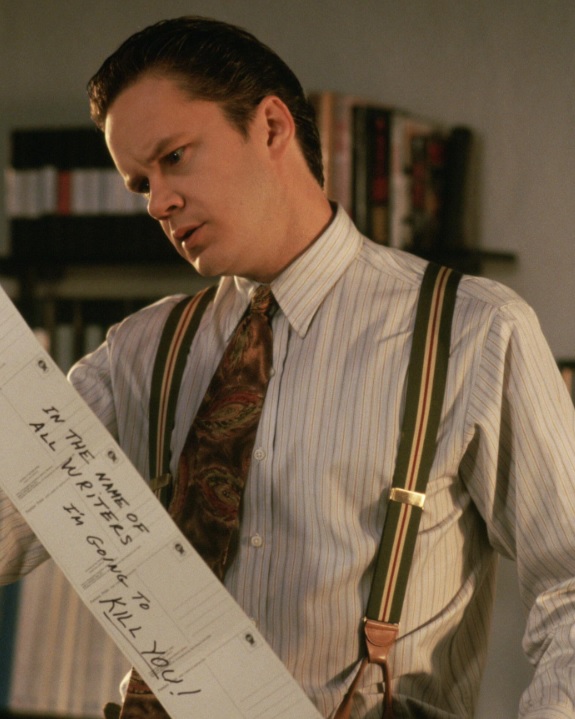

The film’s plot appears to revolve around Mill’s encounter with a disgruntled screenwriter who Mill met once to discuss a screenplay idea but then subsequently rejected. But it’s a MacGuffin—think the statue in The Maltese Falcon—a plot device that really serves only to give Altman a clothesline upon which to string acerbic barbs and scenes jibing the film industry, skewering its narcissistic power dynamics and moral decay.

One of the film’s most striking elements is its self-reflexivity. Altman employs metafictional techniques, blurring the boundaries between the film’s narrative and the reality of filmmaking. At the film’s outset (during a nine-minute tracking shot that pays homage to the beginning of Touch of Evil) we spy on a series of pitch meetings where screenwriters present increasingly absurd and formulaic ideas, all poking fun at Hollywood’s obsession with commercial success over artistic merit. This sets the tone for the film’s overall critique of the industry’s shallow values and creative bankruptcy.

The title itself, The Player, carries multiple layers of meaning. On one level, it refers to Griffin Mill, who manipulates people like pawns in a game to further his own agenda. However, it also alludes to the broader Hollywood ecosystem, where everyone is required to be a player in order to move forward in the pursuit of fame, fortune, and influence. Altman skillfully captures this milieu, populated by ambitious executives, scheming producers, and struggling artists, each vying for their piece of the pie.

Altman’s direction is characterized by his trademark ensemble cast, here fortified by dozens of cameos and fluid camerawork, which lends the film a sense of immediacy and authenticity. The dialogue crackles with wit and cynicism, delivered with pitch-perfect timing by the talented cast.

What elevates The Player beyond mere satire is its willingness to confront uncomfortable truths about the film industry. Altman doesn’t shy away from depicting the industry’s hypocrisy, from its lip service to artistic integrity to its exploitation of talent and obsession with profit margins. The film’s climactic scene, set at a Hollywood party where industry insiders discuss their latest projects with detached cynicism, serves as a damning indictment of the hollow glamour that masks the industry’s moral hollowness.

Throughout the film, Altman challenges audiences to question the values and ethics that underpin the world of filmmaking. The Player stands as an incisive amalgam of cynicism and truth. The most grievous sin, in Hollywood terms anyway, isn’t murder—it’s to make a film that flops.

Edited by Olga Tchepikova-Treon