| Sam L. Landman |

One from the Heart plays at the Trylon Cinema from Friday, June 21st, through Sunday, June 23rd. Visit trylon.org for tickets and more information.

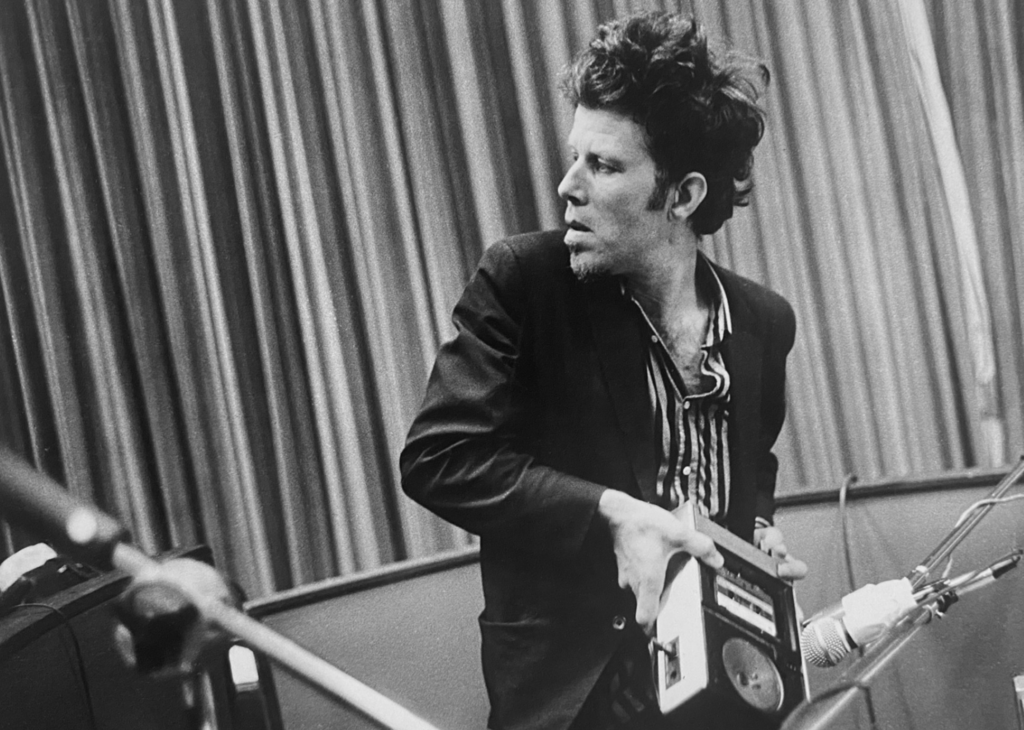

As he ventured onto the American Zoetrope lot in the fall of 1980, fully prepared to write the soundtrack to Francis Ford Coppola’s One from the Heart, Tom Waits had already spent a majority of his career as an imposter. (And I say that lovingly, as a fan who’s cherished the man’s music unconditionally for decades, no matter which blind alley or dark ride he’s taken me through.)

Early on, he’d assumed the guise of a longhaired, folksy, country-fried troubadour. Then, he slipped into the rumpled, cig-stained suit of a scatting, liquor-soaked bowery bum.

Left: Image credit Ed Caraeff, February 14, 1972 . Right: Image credit Tom Hill, November 1978.

But after he’d completed Coppola’s film, Waits would disappear once again, this time into even more abstract and garish costumes: croaking, choking, Weill-ing operatic phantoms, demented junk dealers and surreptitious carnival barkers, all second cousins to Howlin’ Wolf and Captain Beefheart, twice removed. Every era twisted the man, transforming him into a cruel caricature of himself. Like the best Tom Waits impersonator you’ve ever seen.

Left: Image credit Jeffery Newbury, June 17-22, 1986. Right: Image credit Jean Baptiste-Mondino, 2023.

With that in mind, if you’re a Tom Waits fan reading this, it’s important that we broach an uneasy, unspoken subject.

Regardless of your entry point into Waits’ artistic funhouse, you’re undoubtedly aware of the ironclad contract you’ve agreed upon the moment you’ve witnessed him as a walking, talking and, let’s face it, lurching, herky-jerky performer.

But this agreement you’ve entered into is an intricate matchstick bridge. While ostensibly sturdy by all accounts, with every step, you’re conscious of its precarious framework. However, you ignore the probability that it could collapse at any moment. Because you love taking this journey with him. So, all along, you’re emphatically complicit in it. Because you love the façade he’s constructed, no matter how tenuous it is. No matter how much both of you know that none of this is real.

(Simply watch any talk shows he slithered his way onto back in the 70s. They’re striking exercises in forgery, where the perpetrator knows exactly how much snake oil to drizzle into the camera’s eye. [Again, I’m saying this as a fan.])

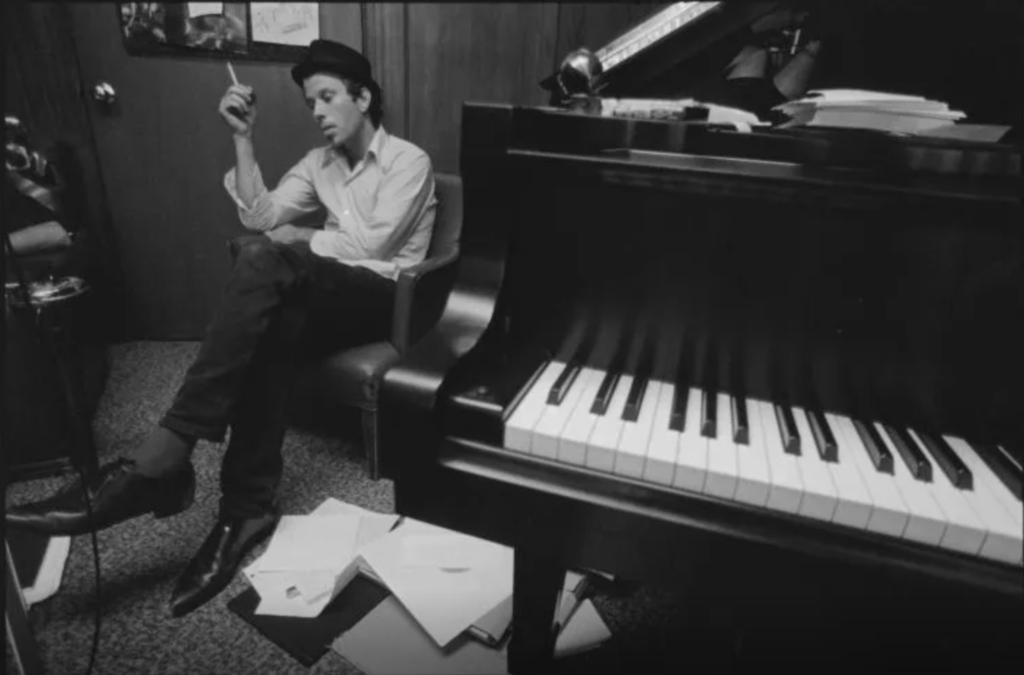

That said, as soon as Waits was employed by American Zoetrope, inhabiting a room no bigger than his cluttered, ramshackle flop at the Tropicana Motel, the bridge started creaking. His carefully sculpted masks began to slip. He found himself shaking off old skin, inhabiting something truer to who he really was, a persona unfamiliar to himself at that point.

Image credit Henry Diltz, 1981

Within that vulnerable state of transformation on that exposed soundstage, he’d meet his future wife, Kathleen Brennan. Her guiding light would burn off parts of the bridge he’d fabricated, altering the course of his listening habits, creative flows, and, ultimately, his career.

Image credit: Pamela Gentile, April 22, 1998

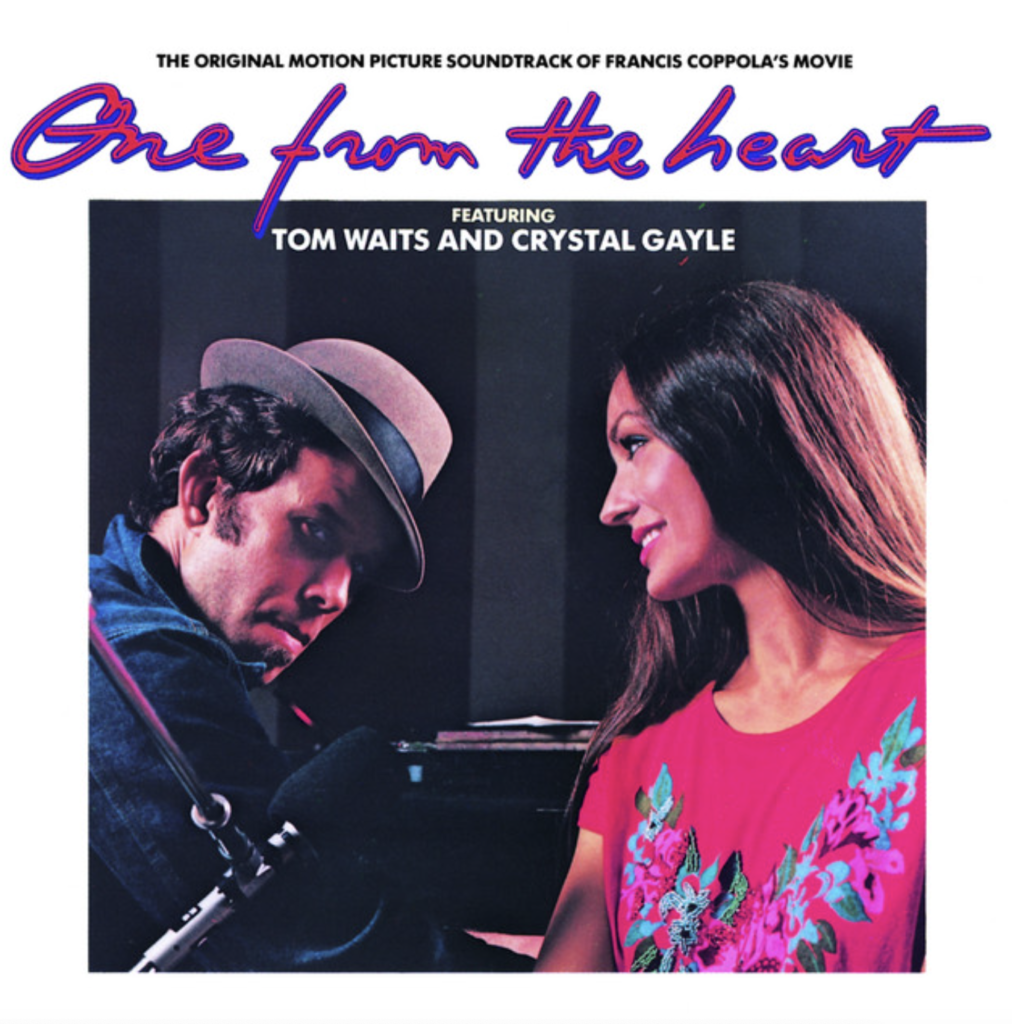

So, as a soundtrack, One from the Heart ignores the existence of that social contract between musician and listener. There’s no longer a bridge for either of you to cross together. This album represents a conduit with which the old Waits melds with a new one; not fully formed yet, but resting in an intermezzo, a purgatory, a place to hunker down for a spell, play solitaire and contemplate escape plans.

It’s within this existential waiting room that we find ourselves now.

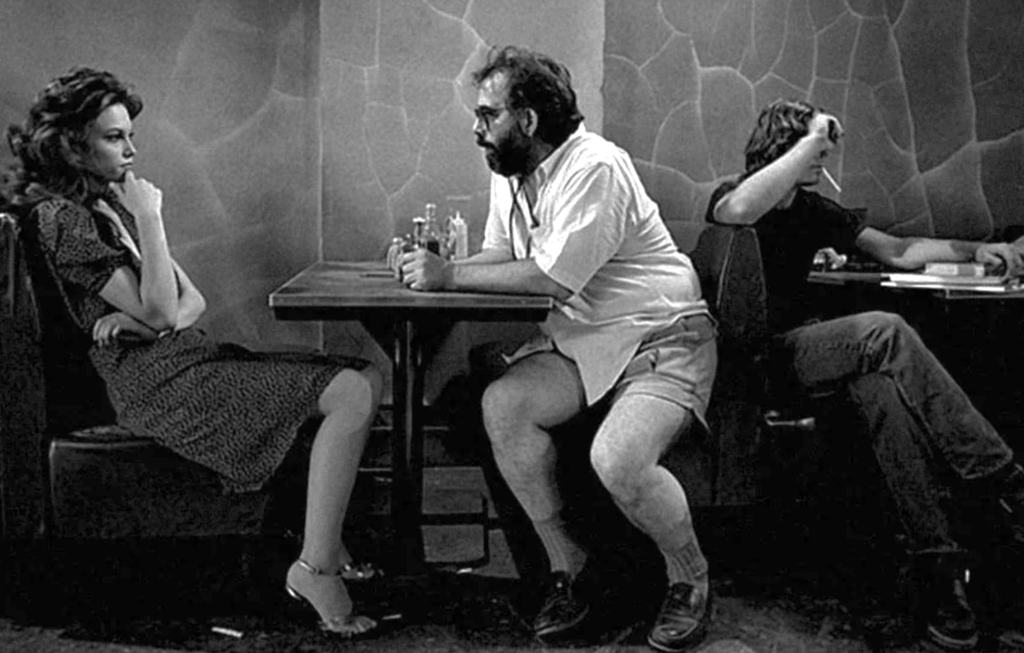

If you separate the film from the soundtrack, something interesting occurs. Two very different storytelling methods emerge, even as Waits provides color commentary for Coppola’s sticky sweet, saturated palette. While they may share an infatuation with rainy streets and downtrodden bit players shoved into the spotlight, that’s where their similarities end.

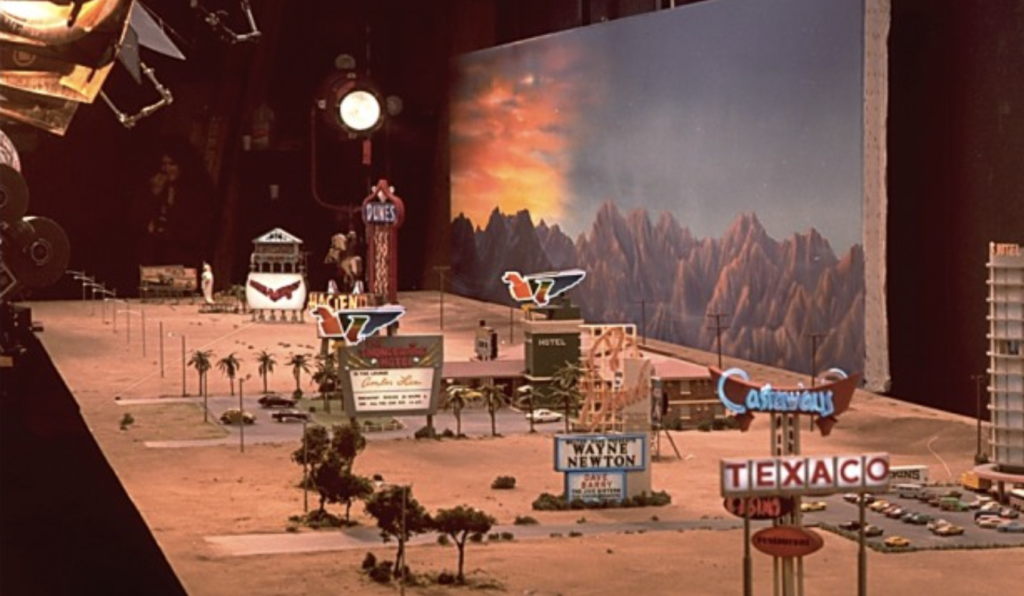

Coppola’s film plays out as all show and technique. There’s an almost intentional simulation to it all. He basically wants you to realize that what you’re watching is indeed taking place on a film set, reminding you that, “Yes, this is, in fact, a movie!”

“That’s a matte painting.”

“Those are scrims.”

“Look, you can see the studio ceiling in this shot.”

“Here’s a continuous take with hundreds of extras, happening right there in real time, right before your eyes, see?”

“I’m the magician and I’m subliminally showing you how every trick is done.”

Meanwhile, Waits plays it all so uncharacteristically close to the vest, he’s practically nowhere to be seen. A phantasm incognito. You’re no longer aware of the slanted fedora perched precariously on his angular noggin, his rigid mummy fingers plonking black keys while pinching an Old Gold, that scrunched scarecrow smile at the storefront of his skeletal mug. There’s nothing to show. The music is his masquerade now. He’s just a jobber, a clock puncher, one of those broken, workaday joes he’s written into many a broken, haunted opus. This is the most temperate, least performative he’s ever been or will ever be.

Image credit David Alexander, 1981

Coppola waves his arms to get your attention.

Waits conceals himself in an upright the size of a Buick.

Waits’ music sprouts from the keys, blooming with new life.

Coppola’s studio flickers on the screen, dying on the vine.

What really sets the soundtrack apart from the movie is how the music can truly stand on its own without the film. It’s its own Waitsian universe outside of the celluloid, whereas the opposite can never be true.

At its core, One from the Heart is Coppola’s love letter to old-school Hollywood musicals, albeit without any of the characters ever really singing (besides Nastassia Kinski or Frederic Forrest [and the less said about that, the better]). The score that Waits provides uplifts the entire affair. Stripping it of its music would cause any heartfelt moment to come crashing down on itself.

That’s why Coppola chose Waits in the first place. The utter power and breadth of Waits’ music, lyrics and down-and-out characters could’ve easily spawned dozens of movies. So, Coppola figured, imagine what his shattered sonatas could do for an actual cinematic experience.

While we’re on the subject, here’s an exercise:

• Find Tom Waits’ catalog (whether on streaming or in your own possession)

• Pick any song before One from the Heart (1973-1980)

• Pick any song after One from the Heart (1983-Present)

• Listen to one, then the other

No matter which tracks you’ve chosen, they’re guaranteed to sound vastly different. But now, listen to any song on the One from the Heart soundtrack.

Image credit David Alexander, October 1982

While audibly, it may seem to have more similarities to his “before” work, there’s a tiny glint, a prescient hint of what’s to come if you’re listening for it.

Take the sullen cataloging of items in “Broken Bicycles.” The blustery hurricane within a Hammond in “Little Boy Blue.” The gruesome raconteur, walloping kettle drums, telling us to “suffer” in “You Can’t Unring a Bell.” And possibly the most prophetic, “Instrumental Montage,” which is one-part debased, sputtering tango and one-part Salvation Army band that’s just been flung down a flight of stairs, then tipped a sawbuck to perform at a shotgun wedding down the hall.

In the end, neither Coppola’s nor Waits’ combined ventures—movie nor soundtrack—would be regarded as successes. If anything, both would disappear without a trace upon release, almost like neither had ever happened.

For Coppola, it’d be a slight dip in a road with many more to come. While his next film, The Outsiders, garnered praise and did well at the box office, most of his follow-ups—some being considered artistic triumphs—would find themselves in similar financial downturns, mirroring One from the Heart.

Image credit Mary Ellen Mark, 1983

For Waits, his relationship with Asylum Records—a label once known for being a haven for singer-songwriters—would represent a sort of sanitarium, one he felt he was literally committed to. But once his wife slipped him a key, he was free to don a new persona and begin carving out new sounds while sunning himself in the bright solace provided by a record label fortuitously named Island.

Image credit Brian Graham, 1985

Both men would cross paths again and again, from film to film. Neither one probably mentioned their initial encounter, a little film with a big budget and a soundtrack that lit up the fabricated heavens like rear-projected fireworks over a forged and phony Las Vegas strip, full of day players and extras, losers and dreamers.

Edited by Olga Tchepikova-Treon

Your articles consistently impress me.