| Courtney Kowalke |

Image sourced from Berlinale Archive

Solei Ô plays at the Trylon Cinema from Friday, November 22nd, through Sunday, November 24th. Visit trylon.org for tickets and more information.

The first movie I saw at Trylon in the spring of 2019 was John Sayles’ The Brother From Another Planet (1984). The film follows a protagonist known only as “The Brother” (Joe Morton), an extraterrestrial who crash-lands in Harlem, New York City. Through a series of vignettes—some more fantastical than others—the film explores the Brother’s search for community and the discrimination he faces since he looks like a Black man.

On the face of it, Med Hondo’s Soleil Ô (1970) reminded me a lot of The Brother From Another Planet. A protagonist credited only as “Visitor” (Robert Liensol) immigrates from Mauritania in northwestern Africa to Paris, France. Through a series of vignettes—some more fantastical than others—the film explores the Visitor’s search for employment and the discrimination he faces as a Black man.

Tonally, however, Soleil Ô couldn’t be any more different from The Brother. The Brother explores racial discrimination with a curious, probing nature. It hits hard in places, but overall makes its points with a light hand. Soleil Ô is a razor. Soleil Ô has an immediacy and an anger I didn’t sense in The Brother. Sayles was asking, “Why do you think society is this way?” Hondo was exorcising a demon.

If it wasn’t already obvious, the inspiration for Soleil Ô was rooted in reality much more literally than The Brother. According to Sayles, The Brother was based on several dreams he had while working on the 1983 drama Lianna.

Soleil Ô, on the other hand, comes viscerally from Hondo’s lived experiences. “I made [Soleil Ô] to serve as a kind of therapy for everything that disturbed me in both my physical and moral life, after all that I’d been through, that others had been through,” Hondo told his longtime cinematographer François Catonnè in a 2018 interview. “I wanted to rid myself of all of it, put it all behind me. I figured as soon as I did that—as long as I did that—I’d be able to turn the page and move on.”

The first time the Visitor appears onscreen in Soleil Ô, the narrator’s voiceover says, “One day, I started studying your writing, reading your thoughts, talking Shakespeare and Molière, and holding forth.” The phrase “talking Shakespeare and Molière” immediately stuck out to me. I quickly realized that was because something similar appears in the biography section of Hondo’s website: “Arriving in Paris, Med Hondo did part time jobs and registered for theatre classes… Then he started to act in classic plays: Shakespeare, Molière, Racine…. And time came when he thought African authors or actors must be represented.”

That last sentence seems more self-important than I sense Hondo was. While Hondo valued creating space for himself and his fellow Black artists, his work often reads as self-critical. Soleil Ô features several digs at Africans who immigrated to Paris to study, as if this is somehow an ignoble goal despite it being exactly what Hondo did in real life. I think it’s also telling that following his “Shakespeare and Molière” reference in the film, the narrator goes on to say, “Sweet France, I am bleached by your culture, but I remain a Negro, as I was at the beginning.” The narrator and Hondo may have read all the ‘right’ books, but that doesn’t make them better than their peers, especially not in white society.

The reality of Soleil Ô is more dreamlike than ours. Sometimes it’s heightened, like when the Visitor witnesses a couple having a screaming match and the camera furiously shakes back-and-forth. Sometimes it’s diminished, like when the Visitor walks through city streets with oddly thin crowds that seem incongruous for the density of Paris. Sometimes reality slips—characters’ voices desync with their mouth movements, a trick I thought was an issue with the copy of the film I was watching until a few seconds later, the camera went out of the back into focus as well. The film wanders in and out of its own scenes and conversations. This isn’t as meandering as it sounds. For example, about twenty minutes in, the Visitor is sent to an interviewer by his employment agency. This interview is interspersed with asides from the narrator about the disconnect between Black and white society, or from other unnamed characters that by turns underscore or contradict what the interviewer and the Visitor are discussing. The effect unsettles any kind of straightforward narrative Soleil Ô might have, but it doesn’t unsettle the audience. All these disparate parts reinforce the message of the whole film.

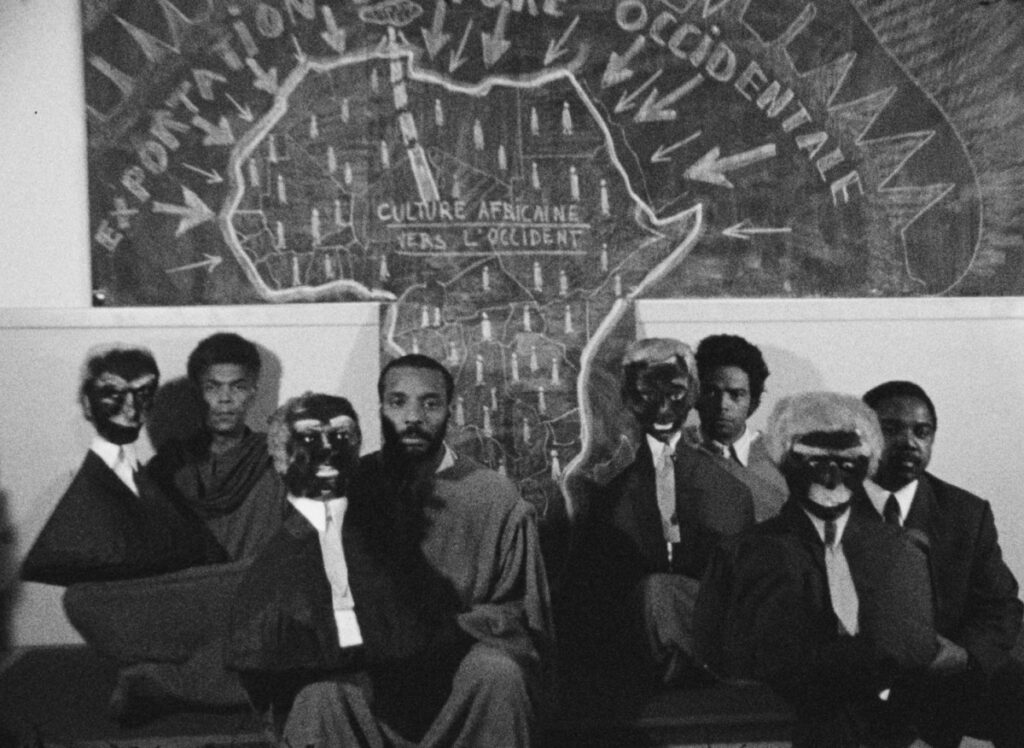

One recurring segment in Soleil Ô features a classroom of Black men being lectured by a white man, often featuring garish papier-mâché puppets. The scenes are meant to be seen as absurd, these grown, autonomous men being treated like children. The scenes are obviously allegorical to Hondo’s experiences as a Black-Arab man, being treated as lower class and in need of education by white society. These segments, however, are also rooted directly in what Hondo describes as his earliest memories of injustice. “Certain schoolteachers would hit their students with a cane in their hand,” Hondo told Catonnè. “They’d beat [their students], telling themselves it was to help them learn. I understood that you could punish the students who refused to study, but why punish the ones who did study” (Catonnè 2:02). Part of Hondo was still in that classroom, pondering the absurdity of what was and wasn’t fair. Part of Hondo took that grain of truth like a grain of sand and rolled it around until it grew into a pearl. The puppets in these scenes seem like a visual reminder of this question, Hondo asking if these stern, silent creations are model students his teachers so desired.

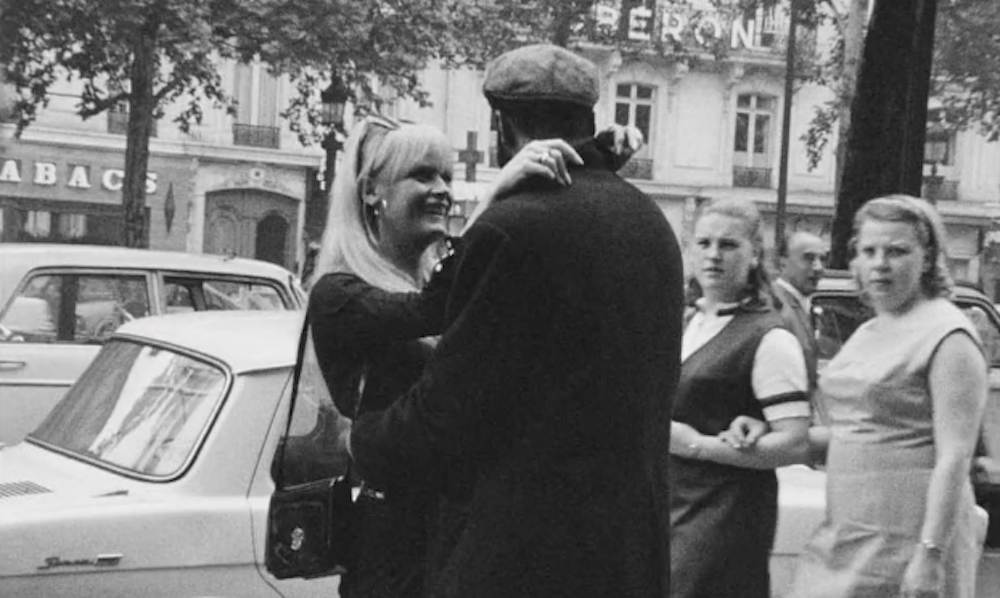

Reality and fantasy also intersect in ways Hondo didn’t script. Late in the film, an unnamed white woman (Michèle Perello) gossips with her friend about how Black men are supposedly better in bed. To test that theory, she then goes out and picks up the Visitor. The pair go for a stroll along the Champs-Élysées, and to quote Hondo, “We set up the camera, and oh, dear. That’s when the racist stares came from every direction. We used up an entire canister of film and then got the hell out of there. We kept thinking maybe it would stop, but it didn’t at all. Racism was very much alive” (Catonnè 18:19). The people gawking at the Visitor and the woman are the same people who alienated Hondo in his daily life.

When asked about the early days of his move to Paris, Hondo told Catonnè, “[if] you were Black, you were either accepted or looked down on, meaning people were either racist or not racist. You never knew if they liked you or if they hated you. And that was a very uncomfortable position to be in. When you live in a society and you’re not sure if you should sit or stand… It’s hard, very hard” (Catonnè 05:19), his unease is palpable throughout Soleil Ô. You don’t need to pull back layers—Hondo is right there, his rage and hurt boiling under the surface. Even the protagonist being referred to as “the Visitor” suggests impermanence, like this man does not belong where he is and he shouldn’t get too comfortable in Paris.

Despite the in-universe hostility, Soleil Ô never feels hostile to its viewers. The film is mesmerizing. Hondo walks the thin line between fantasy and reality like a tightrope. The tone and the film’s vision never waver. It plows straight forward, pulling the viewers along with it.

Edited by Olga Tchepikova-Treon